The ramifications of August 15, 1975

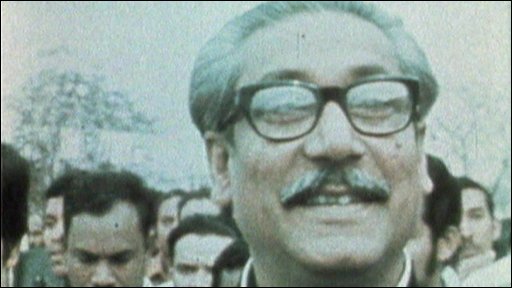

The murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman has had grave ramifications for Bangladesh. It was, in the immediate sense, an overthrow of constitutional government in the country, which was again a reinforcement of the idea that the long struggle Mujib and the Awami League had waged against military rule in Pakistan had in a way come to nought. The coup d’ etat of August 1975 was to be a precursor to other, newer means of removing governments in Bangladesh. The majors and colonels who had organised the large-scale slaughter of the president’s family quickly made it clear that they intended to run the show. They ensconced themselves at Bangabhavan, the presidential palace, and served as Khondokar Moshtaq’s advisors. That was quite in the fitness of things, for he clearly owed his job to them. The biggest irony arising out of the coup was the continuation of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s ministers, save a few, in office. Syed Nazrul Islam, Mansoor Ali and A.H.M. Quamruzzaman were under arrest, along with Tajuddin Ahmed. Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain, abroad at the time of the coup, refused to return and be part of the new administration. But Moshtaq could and did take satisfaction from the fact that all others among his ministerial colleagues were now serving in his regime as his ministers. The first cabinet meeting Moshtaq presided over was on the day after the coup, even as Mujib’s body and the bodies of his family remained to be buried. One of the first bits of information Moshtaq handed out to the ministers, many of whom were plainly terrified, with some others not knowing what position to adopt given the murders that had already taken place, was that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would be buried in his village. There was no regret in his voice, no tribute and not many ministers were willing to raise any questions.

The murder of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman has had grave ramifications for Bangladesh. It was, in the immediate sense, an overthrow of constitutional government in the country, which was again a reinforcement of the idea that the long struggle Mujib and the Awami League had waged against military rule in Pakistan had in a way come to nought. The coup d’ etat of August 1975 was to be a precursor to other, newer means of removing governments in Bangladesh. The majors and colonels who had organised the large-scale slaughter of the president’s family quickly made it clear that they intended to run the show. They ensconced themselves at Bangabhavan, the presidential palace, and served as Khondokar Moshtaq’s advisors. That was quite in the fitness of things, for he clearly owed his job to them. The biggest irony arising out of the coup was the continuation of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s ministers, save a few, in office. Syed Nazrul Islam, Mansoor Ali and A.H.M. Quamruzzaman were under arrest, along with Tajuddin Ahmed. Foreign Minister Kamal Hossain, abroad at the time of the coup, refused to return and be part of the new administration. But Moshtaq could and did take satisfaction from the fact that all others among his ministerial colleagues were now serving in his regime as his ministers. The first cabinet meeting Moshtaq presided over was on the day after the coup, even as Mujib’s body and the bodies of his family remained to be buried. One of the first bits of information Moshtaq handed out to the ministers, many of whom were plainly terrified, with some others not knowing what position to adopt given the murders that had already taken place, was that Sheikh Mujibur Rahman would be buried in his village. There was no regret in his voice, no tribute and not many ministers were willing to raise any questions.

Over the years, much has been made of the fact that it was the Awami League that continued in power after the death of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Opponents of the party have, in their untenable way of explaining why there was no proper trial and punishment of Mujib’s killers (until the Awami League returned to power in 1996), sought refuge behind the spurious argument that Khondokar Moshtaq and everyone else in government after 15 August were part of the Awami League. It was sophistry elevated to newer levels. The facts were actually rather different. On 15 August, there was technically and legally no Awami League since the party had already been subsumed in the larger Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League Mujib had formed in January of the year. More importantly, the ministers who worked, or were made to work, with Moshtaq did so as a result of the plain intimidation that was being exercised on them. In the few months the Moshtaq presidency would last, it was not uncommon for the majors and colonels involved in the August mayhem and murder to make themselves present in the room even as cabinet meetings went on.

One of the first moves Khondokar Moshtaq made was to remove General K.M. Safiullah from command of the army and replace him with his deputy Ziaur Rahman. Additionally, an appointment that raised many eyebrows in the country was the return of General M.A.G. Osmany to government. He was appointed defence advisor to the new president. The alacrity with which he accepted the job somehow stood at variance with the intrepidity he had earlier shown when, in defence of the cause of democracy, he resigned from Parliament once Bangabandhu had formed BAKSAL. It did not appear to worry him overmuch that he was now part of a regime that operated on the basis of murder and extra-constitutional rule. In later years, Osmany would try returning to his democratic moorings through founding a political organisation, the Jatiyo Janata Party. In 1978, he would seek the support of the Awami League in his bid to defeat General Ziaur Rahman at the presidential elections, an exercise he would lose. After August 1975, Osmany’s reputation, built as it had been during the war of liberation and in the early years of Bangladesh, would be on a slide. Enayetullah Khan, editor of the weekly newspaper Holiday, had already made arrangements in the pre-coup period with Sheikh Fazlul Haq Moni to take over as editor of the Bangladesh Times. When he took charge of the newspaper days after Moshtaq seized the presidency, it was given out that he was the new man’s appointee, which was misleading. Khan would in subsequent years relentlessly, almost pathologically carry on anti-Mujib propaganda through his writings. He would serve as a cabinet minister in the Zia regime before serving as General Ershad’s ambassador to China and Burma.

The long-term damage caused by the coup to Bangladesh would be far-reaching and terrible. The biggest damage done to Bangladesh’s democracy and constitutional government was the promulgation of the Indemnity Ordinance by Moshtaq on 26 September 1975. Under the provisions of the ordinance, no individual involved in the assassinations of Bangabandhu and his family could be prosecuted in a court of law since the acts of 15 August 1975 were deemed to have been a historical necessity. In his time, General Ziaur Rahman, clearly the most important beneficiary of the change in August, would incorporate the Indemnity Ordinance through the notorious fifth amendment (now annulled by judicial fiat) into the constitution. The amendment would not only protect the assassins of the country’s independence leader and his political associates (who would be murdered in November 1975) from prosecution but would also pave the way for their accommodation in government. Except for Farook Rahman and Abdur Rashid, all other majors, lieutenant colonels and colonels who had taken part in the coup were appointed to various positions at Bangladesh’s diplomatic missions abroad. One of them, Shariful Haq Dalim, would rise to such heights as the country’s high commissioner to Kenya. In the course of the nine-year military rule of Bangladesh’s second dictator, General Hussein Muhammad Ershad, the leader of the 1975 coup, Colonel Farook Rahman, would form the Freedom Party and contest the presidential elections in 1988.

In the three months following the murder of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the country lurched from one crisis to another, owing to the refusal of the assassin majors and colonels to return to the barracks and thereby enable the senior military establishment to restore the chain of command broken by the coup. But by early November, Brigadier Khaled Musharraf and his loyal officers acquired sufficient support from the ranks to force Moshtaq into jettisoning the junior officers who had installed him in office and were propping him up. On the night of 3 November 1975, Musharraf launched his own coup and was effectively in command of the army, having placed General Zia under house arrest and agreeing to let the coup leaders fly out of the country. Unknown to Musharraf, however, the men who murdered Mujib and his family had made their way to the central jail in Dhaka before their departure for exile abroad and murdered the four leaders of the 1971 Mujibnagar government imprisoned there since Mujib’s assassination. Intriguingly, a rightwing Bengali journalist who had co-produced The Plain Truth, a Pakistani propaganda tract over Dhaka Radio in 1971, let it be known in early November 1975 that he had intercepted letters between Indian intelligence and the imprisoned Tajuddin Ahmed. He spread the word that the Indians planned to spring Tajuddin and his colleagues from jail and install them in power. Within hours of his ‘revelations’, Syed Nazrul Islam, Tajuddin Ahmed, M. Mansoor Ali and A.H.M. Quamruzzaman were brought together in a single cell and bayoneted to death by the soldiers. Asked later about the letters, the journalist claimed he had returned them to his source and therefore could not produce them!

On 6 November, having seen Moshtaq appoint him to the rank of Major General and chief of army staff, Khaled Musharraf forced the usurper to resign. He was replaced by the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem. On the morning of the next day, 7 November, troops loyal to Zia and drawn to the clandestine propaganda mounted by Colonel Abu Taher, an independence war hero and anti-Mujib soldier, about an Indo-Soviet conspiracy to take over the country, mutinied. They were joined by columns of soldiers streaming into Dhaka from Comilla and other cantonments and quickly put Musharraf and his loyalists to flight. General Musharraf, one of the toughest soldiers during the war of liberation and an avowed believer in secular democracy, took refuge along with Colonel Najmul Huda and Major Haider at Sher-e-Banglanagar in the capital. All three men were soon set upon by those they had sought shelter from and brutally killed. As the day progressed, Bengalis knew that a new dispensation was at work. Justice Sayem, who had taken over as president only a day earlier, continued in office, though with the additional responsibility of chief martial law administrator. General Zia, now free and restored to his old job as army chief, was named deputy chief martial law administrator, along with Rear Admiral M.H. Khan of the navy and Air Vice Marshal M.G. Tawab of the air force. Power, of course, was in the hands of Zia who by April 1977 would ease President Sayem out of office and take over as president. In the same month, Zia would organise a referendum seeking his confirmation as Bangladesh’s new leader. Predictably his acolytes arranged the results he needed.

The beginning of General Zia’s rule was also the period when all references to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his role in Bangladesh’s history would be papered over. As president and martial law administrator, Zia would tamper with the constitution through replacing its invocations to secularism and Bengali nationalism. In late 1975, he placed Colonel Taher, who had helped free him from house arrest in November, in jail. After a secret trial by a military court, Taher was hanged on 21 July 1976.

Author : Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Current Affairs, The Daily Star