Bangabandhu before the Liberation..The Road to Independence

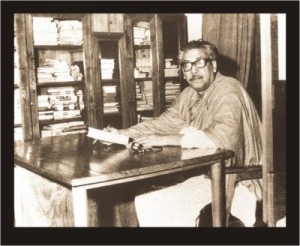

Products and information pervade our times. As we are lost in their all-consuming presence and wide ramifications, there is still, room for remembrance of a leader who, even after 28 years of his death, has simultaneously been at the receiving end of eulogy and criticism.

Products and information pervade our times. As we are lost in their all-consuming presence and wide ramifications, there is still, room for remembrance of a leader who, even after 28 years of his death, has simultaneously been at the receiving end of eulogy and criticism.

Though the image of the man still stands tall, as his public persona is still something to be vied with, the facts behind the making of the leader has been made turbid by subsequent military juntas who rode power in independent Bangladesh. Attempts were made to put a veil on the history of independence and its leader. After he was brutally murdered on August 15, 1975 by a section of highly ambitious and conspiratorial faction of the army, his legacy was deliberately distorted along with history of this nation. Even after democracy was restored in the 90s, the facts were never allowed to surface. SWM strives to piece together the shattered saga of an extraordinary man who still remains the most revered leader of this nation.

After 32 years of independence, history remains a puzzle to a nation that relies too much on word of mouth. Official history, too, has been tampered with. In this context the political life of the leader, who first earned the epithet of ‘Bangabandhu’ in 1969 and ‘the Father of the Nation’ after the liberation, is often seen as a chapter only to be read by the loyal supporters of his party.

During the 23 years of Pakistan rule, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spent twelve years in jail and ten years under close surveillance. Rulers of Pakistan saw him as a leader, who with his charisma and conviction could stir the masses, which he did. Under his charismatic leadership the Bangali people of the former East Pakistan became united as never before and collectively plunged themselves into a movement that later transformed itself to our armed struggle for independence.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was born on 17 March 1920 in the village Tungipara under Gopalgonj district, then a Sub-division in the Faridpur district. His father, Sheikh Lutfur Rahman was a serestadar in the civil court of Gopalganj. His mother’s name was Shahara Khatun. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s initiation to politics began in the Gopalgonj Missionary School, from where he obtained his matriculation in 1942. It was in this school ground that he met Hussain Shahid Suhrawardy and A.K. Fazlul Haque when they came for a visit. Sheikh Mujib had the opportunity to talk to Suhrawardy for the first time, a man who would later become his mentor.

In 1942, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman got admission in the Islamia College in Calcutta. Soon he was to become enmeshed in politics. He started out as an activist of the Student League of Bengal Provincial Muslim League remaining an elected member of All-India Muslim League Council from 1943 onward. There were two factions in Muslim League of Bengal, one was steered by Surhwardy and Abul Hashim and the other by Akram Khan and Khaja Nazimuddin. Mujibur Rahman had become an activist and a supporter of the former. He and the other activists of this faction were often referred to as the Hashemites.

From Islamia College, now called the Moulana Azad College, Mujib obtained his IA in 1944. It was a tumultuous time. The Second World War was ending and on the Azad Hind Fouze Day a youth died near the Baker Hostel, where Mujibur Rahman used to reside. During this time his involvement with politics had intensified. In 1944, he was elected general secretary of the Islamia College Student Union. In 1946, because of his active participation in politics, he could not sit for BA examinations. In the same year the Muslim League sent him to the Faridpur district to campaign for the party in the general elections. The Surhwardy and Hashem faction of the Muslim League won 116 seats in the 119 seats allocated for Muslims. It was an unprecedented victory. Mujib, proved to be an organiser par excellence in this election.

M.R. Akhter Mukul is of the opinion that it was Surhwardy who taught Mujib the tactics of parliamentary politics. And it was from Moulana Bhashani that he picked up his speech making expertise–the emotionally charged, inspiring delivery of his political address. Both had a strong influence in his political career.

After partition of British India in 1947, and having passed his BA from Islamia College, he came to Dhaka and got himself admitted to the University here.

He was a student of law, but he could not complete his study as he was expelled from the university in early 1949 after being charged with ‘inciting the fourth-class employees’ towards agitation. In 1948 under the leadership of Maulana Bhashani and Suhrawardy East Pakistan Awami Muslim League was formed. He was elected one of the joint secretaries of the newly formed party although he was then interned in Faridpur jail. He was one of the leaders behind the formation of the Muslim Students League in 1948. His contribution in the Language Movement of 1952 was also significant. He was one of the first few leaders of the language movement to serve a jail sentence. In 1953, he was elected general secretary of the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League, a post that he held till 1966, the year he became the president of the party.

As an advocate of the rights of the Bangali people, Mujibur Rahman was unrelenting from the very beginning. He always gave voice to issues that had related to economic, social and cultural rights of the Bangalis and to the rising discrimination between the two wings of Pakistan.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, for the first time, was elected a member of East Bengal Legislative Assembly in 1954. It was the year of the rise of people of East Bengal. The United Front (UF), formed by the unity of three leaders- AK Fazlul Huq, Moulana Bhashani and Shaheed Suhrawardy, and all other smaller opposition parties, dealt a death blow to the ruling Muslim League in the election for provincial legislative. The 21-point programme, written by Abul Mansur Ahmad, which articulated the aspirations of the people of the East Bengal created a landslide for the United Front giving it practically all the seats. The Muslim League never recovered from this electoral debacle.

The skirmishing among factions of the UF and all sorts of conspiracies on the part of the West Pakistan authority prevent the United Front from remaining in power dashed all hopes for democracy in Pakistan. On May 19, 1954 the Pak-American defence treaty was signed, and right after that, the United Front government was arbitrarily dismissed and the centre-imposed governor’s rule was put in place. Many leaders were sent to jail including Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.

In the following year, after the dismissal of the United Front government and after Sher-e-Bangla Fazlul Haq broke away from the UF and had secured a place in the centre as the foreign minister, the name Awami Muslim League was changed to Awami League. The decision to omit the word ‘Muslim’ was a sign of departure from the religious oriented politics to a more secular politics.

Mujib entered national parliamentary politics in 1956. He was also a member of the Pakistan Second Constituent Assembly-cum-Legislature from 1955 to 1958. He resigned from the cabinet of Ataur Rahman Khan (1956-58), in which he was the provincial commerce minister, to devote himself to building up the party from the grass root level. His single minded activities to develop the party made a very popular party figure. It also made him a target of the Ayub which jailed him at regular intervals.

It was during his grassroots party activism that Sheikh Mujib developed his own political profile. Although generally under the shadow of his mentor Shaheed Suhrawardy, he started articulating bold, if not radical views on the future of East Pakistan. However he followed his mentor blindly when CENTO and SEATO treaties were signed by Pakistan. For this action a split was created between Suhrawady and Bhashani; in the eyes of left-leaning politicians of East Bengal, Mujib became a part of the pro-American axis. In spite of this, Mujib could be seen as having a left-of-centre political inclination.

As time passed Sheikh Mujib developed extraordinary skill in understanding peoples’ psyche and articulating them in the most effective manner. “He understood his own people, he spoke their ‘language’ and as a leader he was an antidote to the armchair politics practiced by many leaders of that period”, says poet and political analyst Farhad Mazhar.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman takes oath as minister in the Jukta Front cabinet before Chief Minister AK Fazlul Huq on May 15, 1954.

It was Moulana Bhashani who, in his famous Kagmari council session in 1957, hinted at the idea of an independent nation for the Bangalis if Pakistan continued its politics hegemony and oppressing the Bangalis. But the nation had to wait till 1966 to see a strong surge of opinion in favour of self-rule and then later for independence. Sheikh Mujib who had a tremendous sense of timing realised the right moment for articulating the aspiration of the Bangali people for self rule. In 1966, he announced his famous six-point programme at a meeting in Lahore with General Ayub Khan who had taken over power in Pakistan through an army coup in 1958. This, in his own words, was ‘our (Bangalis’) charter of survival’. The six-point programme catapulted Sheikh Mujib into the forefront of national politics united the people of East Pakistan behind a clear cut and easily understood political programme.

As a politician, Mujib always preferred the democratic path to achieve his political goals. He was not a revolutionary in the conventional sense of the term and was always committed to mass movement as a method of political activism. He never propagated the violent overthrow of established regimes however autocratic. As his activism became more vigorous and his mass appeal became stronger and more widespread, the Pakistani regime became more and more oppressive against him. He was frequently arrested and kept interned for longer and longer periods.

1960s was a seminal decade for the Bangalis as well as for Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Although he had spent most of the Ayub era behind bars, Mujib and his Awami League were instrumental in putting up a resistance against the autocracy from the start when Ayub took power in 1958. After the death of giants like Fazlul Haque and Surhwardy respectively in 1961 and 1963, a new era began that saw the rise of a younger generation of politicians. Journalist Ataus Samad gives salience to this, “After the death of Suhrawardy it was Sheikh Shaheb who was responsible for the revival of the Awami League,” he points out. He explains that Sheikh Mujib and Moulana Bhashani are the leaders who spent more than eleven years in roaming around East Bengal, getting to know people at the grass-roots. This he thinks had an effect in how they evolved as mass leaders and how they behaved in the political arena. Although, Samad remarks, in later life Mujib could not rise above party interest.

The Hindu-Muslim riot of 1964 stoked by the then governor Munaim Khan, and the 17 day-long Pak-India war of 1965, were turning points in the political life of the Bangalis. It was during the war that the people of the East Pakistan suddenly became aware of the vulnerability of their position. The army that was being raised with their tax money appeared solely to be geared to protect the western region. Suddenly to the issues of economic, social and cultural autonomy, the issue of defence also became attached.

After Mujib’s six-point programme, the idea of self-rule started to gain a new vigour and unprecedented momentum. As Sheikh Mujib’s popularity rose, the Pakistan’s army government became increasingly desperate. It tried to stop him through frequent imprisonment and other types of oppression. When nothing worked they launched a new attack that of ‘conspiracy against sovereignty of the nation’. A case was instituted that Mujib had conspired with India to dismember Pakistan. As the Agartala Conspiracy case, as it became popularly known, went to trial public support for Mujib’s popularity rose sky high. By then Mujib’s identity was established as the unrelenting champion of the Bangalis, and as the man who unified his people and made them a courageous lot. All this made him the unquestioned leader of his people. Mujib popularity shot up so high that Ayub Khan was forced to withdraw the Agartala Conspiracy case, in the face of united student’s movement under the 11 point charter, and invited him to a ’roundtable conference’ in Islamabad. This military dictator’s surrender to public will further established Mujib’s pre-eminent position as the supreme leader of the Bangalis.

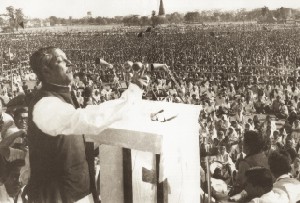

“Ebarer sangram amader shadhinoter sangram”—–The historic address at the Race Course ground, March 7, 1971.

In the round table meeting, Mujib was not willing to make any concessions on his six-point demands. The meeting failed to produce any result. After two weeks, on March 24, 1969, Ayub was forced to step down. Army chief, General Yahya Khan took over power in a bloodless coup.

Then came the general election of 1970. December 9 was the day of elections, and the army stood guard while the electorate gave a huge mandate in favour of Awami League. Without competing in the West Wing of Pakistan, AL secured 167 seats. This was the historical achievement of the pro-self-rule people led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Mujib was successful in making the Bangalis speak with one voice and that was a voice for their economic, social and cultural emancipation.

The historic address of March 7, 1971, in the then racecourse (now the Suhrawardy Udyan), by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a clarion call for an independent Bangladesh.

Farhad Mazhar believes that Mujib was a believer in the parliamentary system, and in his address to the public, he never clearly proclaimed independence although it was, at that time, taken as a call for independence; he did not ask the people outright to take up the gun, but he did imply it in a very emotional way.

He fought for a democratic form of government, yet he knew that independence was the only way. Although the student leaders of various parties had been calling for independence since March 2, he kept on trying to at find a peaceful solution through a legal procedure. The dialogue he continued with general Yehya and Bhutto is proof of this. The effort failed, as Mujib did not compromise the interest of the Bengali people.

Leaders of West Pakistan came to Dhaka to talk, but when the talk was on the verge of collapse, they left for west Pakistan leaving the Bengali people to face a genocidal crack down by the Pak military on the night of March 25. Sheikh Mujib was arrested on the same night from his Dhanmondi residence and kept incarcerated at the Dhaka cantonment until he was flown to West Pakistan to be tried on charges of sedition. Farhad Mazhar lauds his action at this critical moment. His courage to wait in his own home without knowing his fate was exemplary.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman did not physically participate in the armed struggle for the Liberation of Bangladesh. But in every freedom fighter’s lips his name resonated and with every heartbeat they felt his presence. The massive sea of people who welcomed him back on 10th. January 1972 when he was released from Pakistani prison proved how much the people, of now independent Bangladesh really loved and revered him.

Author : Mustafa Zaman