Founding father under siege . . .

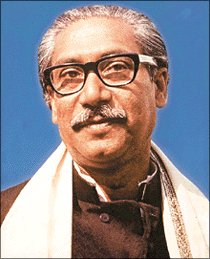

/0 Comments/in Articles, BOOKS /by RonZ Abdul Matin’s persistence in keeping the historical record straight for Bangladesh is admirable. More to the point, it has been a necessary truth in the collective life of the Bengalis. You could suggest that if Matin were not around to keep us focused on the politics of Bangladesh as it was forged and pressed forward in the 1960s and the 1970s, there would be a huge need to go looking for someone of his kind. Obviously, Matin has done his job well. His preoccupation with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains, a particular reason being his understanding that the founding father of Bangladesh has, directly as also indirectly, been under unremitting siege since his assassination in August 1975. To be sure, over the years, Bangabandhu’s legacy has regained some of its earlier lustre, thanks principally to the particularly strong niche his daughter Sheikh Hasina occupies in national politics and thanks also to the concerted struggle his party, the Awami League, has waged over more than three decades to restore his reputation as the man behind the creation of Bangladesh.

Abdul Matin’s persistence in keeping the historical record straight for Bangladesh is admirable. More to the point, it has been a necessary truth in the collective life of the Bengalis. You could suggest that if Matin were not around to keep us focused on the politics of Bangladesh as it was forged and pressed forward in the 1960s and the 1970s, there would be a huge need to go looking for someone of his kind. Obviously, Matin has done his job well. His preoccupation with Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains, a particular reason being his understanding that the founding father of Bangladesh has, directly as also indirectly, been under unremitting siege since his assassination in August 1975. To be sure, over the years, Bangabandhu’s legacy has regained some of its earlier lustre, thanks principally to the particularly strong niche his daughter Sheikh Hasina occupies in national politics and thanks also to the concerted struggle his party, the Awami League, has waged over more than three decades to restore his reputation as the man behind the creation of Bangladesh.

The work under review is fundamentally an addition to the position Matin has adopted, through his earlier books, on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He believes, and quite rightly too, that the slings and arrows which have been hurled at Bangabandhu are of a nature that ought not to be taken seriously and yet cannot quite be ignored because of the fair degree of consistency with which his detractors have been trying to run him down posthumously. Many have been the instances when Mujib was castigated for the way he administered the country between 1972 and 1975. It is such criticism which Matin counters in this work. And in doing so, he makes sure that his arguments are backed by necessary documentary references. An instance of it relates to the declaration of independence on 26 March 1971 moments into the genocide launched by the Pakistan army in Dhaka. Matin quotes from United States government documents to underscore the point that Bangabandhu made the call for freedom soon after the army fanned out to different locations in the city.

Obviously, a good deal of what the writer presents here is by now the historical truth. The difference between Matin and the others who remain aware of national history as it developed after March 1971 is that the former bases his statements on well-founded recorded material. He never misses giving readers the footnotes that scholarly work demands, something that a large number of Bengali chroniclers of national history have generally failed to do. It is against such a background that the reader is given to understand the circumstances behind Mujib’s release by the government of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in early 1972 and his subsequent flight to freedom. Matin admires the sagacity in the Bengali leader, a sign of which comes through in the withdrawal of Indian troops from Bangladesh in March 1972. Without saying as much, the writer conveys the impression that the withdrawal could not easily have come to pass had Mujib not been around. In bare terms, the physical presence of Bangabandhu on the Bangladesh scene was to prove pivotal in a good number of ways. The upshot of it all is that Matin appears to be convinced that the troubles Bangabandhu’s government faced in those formative years of Bangladesh’s history were in more ways than one the result of the conspiratorial politics his government could not quite put its finger on. To a very large extent, he is right. But then comes the matter of the rift between Bangabandhu and Tajuddin Ahmed. It is here that Matin appears to be sailing against the wind when he asserts that in quite a number of ways the man who led the wartime Mujibnagar government as prime minister dealt some bad body blows to Mujib even as he served as finance minister in Bangabandhu’s government. Contrary to popular belief that Tajuddin Ahmed found himself increasingly sidelined in Bangabandhu’s government, largely because of his enemies getting better access to the prime minister, Matin is excoriating about what he considers to be the finance minister’s perfidy in finding fault with the way Bangabandhu ran the administration. Matin’s considered opinion is that Bangabandhu’s Second Revolution was essentially what the Father of the Nation said it was: that the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (Baksal) was a platform that brought together the nation’s political parties together in the larger national interest. Tajuddin had a different perspective on the development, of course.

There are some bare truths Matin reveals here. The story of how Serajur Rahman, he of the BBC’s Bengali Service, was thwarted in his attempts to come by a job in Bangabandhu’s government is what the writer relates, no holds barred, in the work.

Read the book. It adds to your understanding of the forces which shaped politics in Bangladesh in the early 1970s.

. . . Symmetry of the grand and the banal

ASAFUDDOWLAH’S has been a vibrant presence on the Bengali social and bureaucratic scene. His is and has always been an articulate voice. As a civil servant, he was known for his sense of independence, to a point where many thought twice about coming across him. Rare was the individual who wished to fall foul of him, for Asafuddowlah did not mince words when it came to offering an opinion on men and matters. It was always strength of character that defined the man. And it is something that continues to underpin his perspectives on things around him. On television chat shows, he offers his own clear assessments of political conditions, some of which may not go down well with his detractors. They may, indeed do, find him abrasive at times.

The point here is that Asafuddowlah remains indifferent to all such expressions of sentiment about him. His outspokenness is all. And with that comes the other side of his personality, that which keeps him riveted to the world of music. Even as he has pursued a career in the civil service, first in Pakistan and then in Bangladesh, he has made sure that songs have remained close to him, or he to them. He has composed music, he has lent his voice to songs and he has discoursed on them. His rendering of ghazals has been remarkable. Anyone who has heard him sing the old Jagmohan number, ik baar muskura do, will know of the artistry he is capable of calling forth. In his wider social ambience, Asafuddowlah is the quintessential conversationalist, with an interplay of serious thought and humour that make him stand out as the star in the crowd.

And this is the background against which Of Pains and Panics must be read. Asafuddowlah falls into the mould of those who came of age in an era of enlightenment and then went on to reshape the era according to their specifications. Like many of his social club, he has believed in approaching life from an intellectual point of view. Just how much of suavity he has brought into his observations of life comes through in this eminently readable compendium of his thoughts on an array of subjects not many would care to spend time on these days. There are clear divisions of the essays into wide-ranging swathes of territory. Begin with music. There is a sense of certainty, for obvious reasons, with which he approaches the many strands of the subject. He takes the BBC to task, for all the right reasons, over its selection of historically notable Bangla songs. It is pretension he slices through here. And then he moves on to pay obeisance to the artistes who have with regularity enhanced the quality of Bengali music. Protima Banerjee is one he reveres. Another is the all-encompassing Kamal Dasgupta. The music director, he informs us, remained self-effacing right till the end. And as the end approached, as he was being wheeled into hospital, the officer on duty had an asinine question: was Dasgupta a class one officer? Ah, artistes lose out, often if not always, to the bureaucracy!

Some of the most touching of articles in this collection connect Asafuddowlah to those he was once close to, until death intervened to take them away. He writes with deep affection on his mother and then reflects on his father. Perhaps a coruscating part of the tribute to Khan Bahadur Moulvi Mohammad Ismail is the praise he showers on his niece Komli (‘…his youngest daughter’s youngest daughter, Komli, who he used to adoringly call ‘Chand di’, nursed him in his fading days with a kind of special devotion I have never witnessed in my life’). It is a vast world of thoughts Asafuddowlah covers in the work. His views on America are a sharp response to Washington’s actual behaviour on the global scene. In Bangladesh, he wonders aloud at the swift decline in the quality of politics, almost to a point where the powerful begin to think of themselves as little gods. There is a symmetry he establishes between the grand and the banal. How else would you observe his tribute to Ustad Salamat Ali Khan and then his consternation at the presence of so many ministers in the government of as small a country as Bangladesh?

Asafuddowlah is combustive by nature. That is his assessment of himself. Just how combustive — and combative — he can be is an exercise you might as well opt for through reading these pieces. He is not being didactic; he carefully avoids scaling the Olympian heights that lesser men always strive for. He gives you the workings of his mind as they happen to be — blunt, irreverent but playing with ideas all the same.

Two reviews from Syed Badrul Ahsan / Syed Badrul Ahsan is Editor, Current Affairs, The Daily Star.

Early Independence Period, 1971-72

/0 Comments/in Articles /by RonZThe “independent, sovereign republic of Bangladesh” was first proclaimed in a radio message broadcast from a captured station in Chittagong on March 26, 1971. Two days later, the “Voice of Independent Bangladesh” announced that a “Major Zia” (actually Ziaur Rahman, later president of Bangladesh) would form a new government with himself occupying the “presidency.” Zia’s selfappointment was considered brash, especially by Mujib, who in subsequent years would hold a grudge. Quickly realizing that his action was unpopular, Zia yielded his “office” to the incarcerated Mujib. The following month a provisional government was established in Calcutta by a number of leading Awami League members who had escaped from East Pakistan. On April 17, the “Mujibnagar” government formally proclaimed independence and named Mujib as its president. On December 6, India became the first nation to recognize the new Bangladeshi government. When the West Pakistani surrender came ten days later, the provisional government had some organization in place, but it was not until December 22 that members of the new government arrived in Dhaka, having been forced to heed the advice of the Indian military that order must quickly be restored. Representatives of the Bangladeshi government and the Mukti Bahini were absent from the ceremony of surrender of the Pakistan Army to the Indian Army on December 16. Bangladeshis considered this ceremony insulting, and it did much to sour relations between Bangladesh and India.

At independence, Mujib was in jail in West Pakistan, where he had been taken after his arrest on March 25. He had been convicted of treason by a military court and sentenced to death. Yahya did not carry out the sentence, perhaps as a result of pleas made by many foreign governments. With the surrender of Pakistani forces in Dhaka and the Indian proclamation of a cease-fire on the western front, Yahya relinquished power to a civilian government under Bhutto, who released Mujib and permitted him to return to Dhaka via London and New Delhi.

On January 10, 1972, Mujib arrived in Dhaka to a tumultuous welcome. Mujib first assumed the title of president but vacated that office two days later to become the prime minister. Mujib pushed through a new constitution that was modeled on the Indian Constitution. The Constitution–adopted on November 4, 1972–stated that the new nation was to have a prime minister appointed by the president and approved by a single-house parliament. The Constitution enumerates a number of principles on which Bangladesh is to be governed. These have come to be known as the tenets of “Mujibism” (or “Mujibbad”), which include the four pillars of nationalism, socialism, secularism, and democracy. In the following years, however, Mujib discarded everything Bangladesh theoretically represented: constitutionalism, freedom of speech, rule of law, the right to dissent, and equal opportunity of employment.

NOTE: The information regarding Bangladesh on this page is re-published from The Library of Congress Country Studies. No claims are made regarding the accuracy of Bangladesh Early Independence Period, 1971-72 information contained here. All suggestions for corrections of any errors about Bangladesh Early Independence Period, 1971-72 should be addressed to the Library of Congress.

The day Bangabandhu came home

/0 Comments/in A Brief, Articles, History /by RonZTHE crowds began converging in front of Tejgaon airport at dawn. By early morning, the place was dense with people — young and middle aged, with a smattering of the aged — come to welcome the founding father of the new state of Bangladesh, back home from ten months of captivity in Pakistan. It was January10, 1972. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was flying home from London, whence he had been flown by the Pakistan authorities a couple of days earlier.

The whole of Bangladesh was in celebratory mode on the day, indeed had been since news had first come in of Bangabandhu’s arrival at London’s Heathrow airport from Rawalpindi. On January 8, though, when Bengalis first heard of their leader’s departure from Pakistan, a certain kind of panic and a sense of apprehension set in about his safety. That was again natural, for ever since his arrest by the Pakistan army in the early hours of March 26, 1971, he had not been seen in public.

He had been flown to the then West Pakistan and placed in solitary confinement in Lyallpur jail. In Bangladesh, the genocide organised by the military regime of Yahya Khan was well underway, thanks to the ruthless Tikka Khan. In the nine months between March and December of the year, 3,000,000 Bengalis were murdered and 200,000 Bengali women were raped by the soldiers of the Pakistan army.

No one in occupied Bangladesh knew if Mujib was dead or alive. The first indication that he had not been put to death came on August 9, when state-owned Radio Pakistan put it about that the Bengali leader would be placed on trial on August 11 on charges of treason before a military tribunal whose proceedings would be conducted in camera. The eminent Pakistani lawyer A.K. Brohi, it was revealed, would be Mujib’ defence counsel. In the subsequent weeks, Yahya Khan made quite a few references, all derogatory, to Bangabandhu in the course of some media interviews.

By late November, as was to be known later, the tribunal had found Bangabandhu guilty of treason, with the very likely possibility of the judgement soon leading to his execution. But then came the Indian entry into the war between Bengalis and Pakistanis on December 3, prompted by Pakistani air force jets striking Indian cities on the border with West Pakistan. By December 16, all was over for Pakistan, as Bangladesh stood liberated through the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani soldiers.

Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who took over as Pakistan’s new president from Yahya Khan on December 20, ordered the placing of Bangabandhu, who had triumphed over him at the general elections of a year earlier, under house arrest on December 22. On December 27, Bhutto turned up at the rest house where Mujib had been placed on his orders. It was the first meeting between the two men after the abortive political negotiations in Dhaka in March.

Bhutto’s goal was clearly to extract promises from Bangladesh’s leader about some form of links between Pakistan and its now free eastern province. Mujib did not oblige him.

On January 3, 1972, addressing a public rally in Karachi, Bhutto rhetorically asked his audience if they would permit him to free Mujib. The crowd roared its approval. As the night deepened on January 8, Bhutto accompanied Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman to Rawalpindi’s Chaklala airport. Mujib was being freed, along with his constitutional adviser Kamal Hossain and family (Hossain had been arrested in early April 1971 and placed under detention in West Pakistan). Senior officers of the Pakistan military accompanied Bangladesh’s founder on the special PIA flight taking him to London.

Bangabandhu was received at Heathrow by officials of the British Foreign Office as well as the senior-most Bengali diplomat of the time, M.M. Rezaul Karim, and other members of the Bangladesh mission in London. Soon after his arrival, he called on British Prime Minister Edward Heath and opposition leader Harold Wilson. He called his family in Dhaka and also spoke to Prime Minister Tajuddin Ahmed on the phone. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi called him and greeted him on his release from imprisonment. In the evening of January 8, Bangabandhu addressed a packed news conference at Claridge’s hotel and paid tributes to his nation on attaining victory in an “epic war of liberation.”

Bangladesh’s president, for that was the position Bangabandhu occupied as a result of a decision by the provisional government at Mujibnagar on April 17, 1971, left London late the next day on a special aircraft put at his disposal by the British government. The next morning, January10, he broke journey in New Delhi, where he was warmly welcomed by President V.V. Giri, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, members of the Indian cabinet, and civil and military officials. He addressed a public rally thanking Indians for their support to Bangladesh’s liberation struggle. And then he took off, this time for home.

He arrived in Dhaka at 1.40 in the afternoon to a rapturous welcome from his people. The truck carrying him, in the company of Bangladesh’s government leaders, to the Race Course took nearly three hours to reach its destination. At the Race Course, Bangabandhu broke down in tears as he paid tribute to the millions who had sacrificed their lives for freedom.

He was happy his Golden Bengal was finally free, happy that Bengalis had emerged free of Pakistan. It was twilight when he and the million strong crowd made their way home after what been a dramatic day.

Source : The Daily Star

Struggle of the Phoenix

/0 Comments/in Articles, Biography /by RonZ I recently met an old woman passing her days by in a wheelchair. Time takes its toll on even the best of us, and looking at this eighty plus elegant lady I instinctively realized that she would like nothing better than a happy exit from our grind. I used to regularly take her comments while working at the Deutsche Welle, Germany. In the 1950s Ruqayya Jafri was an active politician, she learnt politics from Suhrawardy while on campaign trail in North Bengal. Amongst her contemporaries Shaikh Mujib was also a part of their journey.

I recently met an old woman passing her days by in a wheelchair. Time takes its toll on even the best of us, and looking at this eighty plus elegant lady I instinctively realized that she would like nothing better than a happy exit from our grind. I used to regularly take her comments while working at the Deutsche Welle, Germany. In the 1950s Ruqayya Jafri was an active politician, she learnt politics from Suhrawardy while on campaign trail in North Bengal. Amongst her contemporaries Shaikh Mujib was also a part of their journey.

Ruqayya Jafri later became more friends with Fatema Jinnah, but her admiration for Mujib remains the same till date. They had an interesting dynamics, she would constantly suggest books to Mujib to read and persistently followed up on that reading. Even though there were times when Mujib could barely take out time from his political commitments, he would sacrifice whatever little personal time he had to read the fat volumes. It was either that or to face Ruqayya apa. That was the culture of diversity and political tolerance which Shaikh Mujib tried to maintain throughout his life. His friendships remained illuminated even when the friends chose to follow a different or adverse political cause.

Mujib never took food without ensuring the same for his team members. Ruqayya Jafri can recall so many occasions like that. In her eyes Mujib was an extraordinary man deeply in love with the soil and soul of Bengal. She is witness to several political brainstorming sessions between Mujib and his mentor Suhrawardy, always in impeccable English. To her that was the time Mujib was passionately preparing himself for a freedom flight.

During our discussion, she asked me about the impression that Mujib carries today among the masses of Bangladesh after decades for historical distortions. She didn’t need my answer as she knows the strength of the Phoenix, but she is clearly hurt by BNP’s defamation of Mujib. In all her time in Pakistan Ruqayya Jafri never saw Bhutto’s People’s Party utter a single word against Jinnah, just as defaming Gandhiji is disliked in India. She is a Bengali woman, so it’s heartbreaking for her to see her race dishonoring their Father of the Nation. Atleast for this sensitivity she still carries respect for Indians and Pakistanis.

While working as a civil servant in 1999 at the National Broadcasting House in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the personal logistic staff assigned to me had served our father of the nation during his early years. It was also a matter for honor for me, so while I preferred to carry my own files, he assisted me like an ancient mariner serving me with his memories of Dhanmondi 32 Line.

To this ancient mariner Bangabandhu was an easygoing, informal man, with a sense of humor, who would often inquire about this little man’s personal wellbeing, generously tipping him whenever he could. He narrated Bangabanghu as his dream man who never took dinner without ensuring this orderly’s food, who didn’t differentiate between affections for his own children and the kids of his domestic helps.

Ruqayya Jafri in Karachi seconded the tales of this orderly, who is now in his seventies, wears specs and gazes at the sky to salute the star who always had a smile for him. This orderly withdrew from society after the killing of Dhamandi 32. He lost his position, was tortured by war criminals and his claims for getting his job back were repeatedly refused by the Jatiyo party and BNP governments. So in 1997 he got in touch with prime minister Shaikh Hasina and got his job back. But by then he had lost his concentration and even his appetite. I found him to be in a constant sense of trauma. While working for an audience program on Bangabandhu, I saw him fixing the photograph of the father of the nation with pain and tears.

In 2001 when BNP-Jamaat took over the reign, BNP cadres started ragging him. I was organizing an exit strategy for myself and in the process tried to get him a job at the Bishya Sahityo Kendra (World Literature Center, Dhaka) or some other good place like that, but he stopped me from doing do. He had lost all interest in a job. We separated on July 31, 2002, with tears and uncertainity. However, I will be ever grateful to this ancient mariner for showing me how the Phoenix rose from the ashes, and for helping me reinforce my belief in Shaikh Mujibur Rahman.

I have omitted this ancient mariner’s name deliberately to ensure his safety because he is among the few living proofs of the supermanhood of Bangabandhu.

Author : By Maskwaith Ahsan

Untitled

The Day make the victory completeমে 10, 2019 - 8:43 অপরাহ্ন

The Day make the victory completeমে 10, 2019 - 8:43 অপরাহ্ন “Bangabandhu” – An illustrious leaderমার্চ 30, 2018 - 8:06 অপরাহ্ন

“Bangabandhu” – An illustrious leaderমার্চ 30, 2018 - 8:06 অপরাহ্ন Unesco recognises Bangabandhu’s 7th March speechঅক্টোবর 31, 2017 - 12:15 অপরাহ্ন

Unesco recognises Bangabandhu’s 7th March speechঅক্টোবর 31, 2017 - 12:15 অপরাহ্ন National Mourning Day observedআগস্ট 16, 2016 - 12:39 পূর্বাহ্ন

National Mourning Day observedআগস্ট 16, 2016 - 12:39 পূর্বাহ্ন National Mourning Day todayআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 1:43 অপরাহ্ন

National Mourning Day todayআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 1:43 অপরাহ্ন

L A T E S T

Political Career

Bangabandhu had no illusions about Pakistanisআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 12:44 পূর্বাহ্ন

Bangabandhu had no illusions about Pakistanisআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 12:44 পূর্বাহ্ন HIS GREATNESS CANNOT BE TARNISHEDএপ্রিল 14, 2015 - 8:03 অপরাহ্ন

HIS GREATNESS CANNOT BE TARNISHEDএপ্রিল 14, 2015 - 8:03 অপরাহ্ন THE STORY OF AN INSPIRATIONAL FIGUREজানুয়ারি 17, 2014 - 2:20 অপরাহ্ন

THE STORY OF AN INSPIRATIONAL FIGUREজানুয়ারি 17, 2014 - 2:20 অপরাহ্ন The Declaration of Independenceজুন 6, 2013 - 5:49 অপরাহ্ন

The Declaration of Independenceজুন 6, 2013 - 5:49 অপরাহ্ন The day they killed Bangabandhuজুন 6, 2013 - 5:34 অপরাহ্ন

The day they killed Bangabandhuজুন 6, 2013 - 5:34 অপরাহ্ন