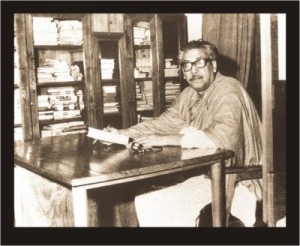

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in his library

On his final night alive, hours before he was assassinated, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman spent time reading George Bernard Shaw’s Man and Superman. Thirty four years after the murder of the Father of the Nation, and the members of his family, Syed Badrul Ahsan makes note of some of the books that have been written about Bangabandhu since 1975. Of course, there are other books as well. But the offering here is a sample of the vast literature which has grown up around the historical personality of Bangladesh’s founding father.

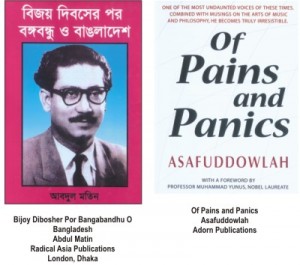

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Koekti Oitihashik Dolil

Abdul Matin

Radical Asia Publications

Abdul Matin has been researching Bangabandhu’s life and politics since the early 1970s. He has perhaps some of the most widely sought after documents relating to the Father of the Nation. In this work, he draws extensively from documents previously in the hands of foreign governments, notably the United States, to explain the circumstances that led to the assassinations of August 1975. There are too some rich pickings from Keesing’s, those that will be of immense help to anyone interested in studying the history of Bangladesh. Matin’s is one of those books that stay away from panegyrics and instead focuses on the core issues he feels need to be discussed within Bangladesh and outside. It is especially the conspiracy that led to the killing of the Father of the Nation that arouses his interest. Included in the work under survey are some hard truths, those that political authors have sometimes pointed out. Among them are details pertaining to the letter purportedly written by the leftwing Bengali politician Abdul Haq to Pakistan’s prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto seeking assistance in the matter of pushing Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s government from office.

Sheikh Mujib, Triumph and Tragedy

S.A. Karim

The University Press Limited

The work is to be read for a special reason, which is that it happens to be one of those rare studies in the English language of Bangladesh’s founding father. For years there has been a vacuum where presenting Bangabandhu to the outside world is concerned (not that much headway has been made in the matter). So what S.A. Karim, who served as a leading Bengali diplomat in the early years of a free Bangladesh and who saw many of the dramatic events unfold before his very eyes, does here is present an image of Bangabandhu and his leadership of the country in as realistic a manner as possible.

The writer does not shy away from criticism of Mujib he feels is deserving. He appreciates the manner of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s rise on the national scene and dwells at length on the history behind the emergence of the man who would eventually be Bangabandhu. Mujib’s role in the movement for regional autonomy and his leadership of the independence movement, which really commenced in early March 1971, are commented on in great detail. And then Karim moves on to the sensitive issue of why Mujib went for a change from multi-party democracy to one-party rule in early 1975. In the manner of so many others, the author does not appreciate the transformation and ends up giving the impression that Baksal was a bad move for which Bangabandhu paid dearly. Karim, like so many others, happens to be rather correct in his observation of the events which were to lead to the carnage of August 1975. A good book, this. Perhaps a better one will find a place on coffee tables in the years ahead.

Shorone Bangabandhu

Faruq Choudhury

Mawla Brothers

The former diplomat is, like millions of people in Bangladesh and elsewhere, in awe of Bangabandhu. In this slim volume, he reflects on the politics of the Father of the Nation and, more importantly, on the human qualities of the man. The language is simple and lucid and Choudhury properly gives out the impression that he is hugely impressed by the charisma of the leader.

Faruq Chowdhury’s work does not go into the intricate details of how Bangabandhu governed or how his government functioned. But that the government was confronted with a plethora of difficulties from day one to the end of Bangabandhu’s life is made clear. And, of course, the vast conspiracy that was always at work in order to destabilize the government is broadly hinted at. The book makes cool reading.

Sheikh Mujib, Bangladesher Arek Naam

Atiur Rahman

Dipti Prokashoni

One of the newest works on Bangabandhu’s politics, it promises much to those who plan to research the evolution of East Pakistan into Bangladesh. The life of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, so Atiur Rahman conveys the impression and justifiably too, is fundamentally the history of Bangladesh, of the struggles its people have carried on through generations.

The author does a marvellous job of bringing together all the significant events of Bangabandhu’s political career. But surely the beauty of the work lies in the detailed, chronological presentation of facts he engages in. It is thus that the Six Points, Eleven Points, Declaration of Independence, et cetera, come to readers in a form that enable them to understand the movement of history in this part of the world. Atiur Rahman is of course gushing in his praise of Bangabandhu and consciously stays away from taking a critical stand. But that, given the whole tenor of the book, is understandable. On balance, it is a useful work, not to be ignored.

Shotrur Chokhe Bangabandhu

Dr. Mohammad Hannan

Anupam Prakashani

A work that is rather different from the usual assessments that are made of the Father of the Nation and his politics. Mohammad Hannan focuses on the views people not kindly disposed toward Bangabandhu happen to express about him. In a way, one could say, the author is coming forth with the other side of the picture, that which Mujib’s opponents have drawn up of his politics.

You may not be convinced by what Bangabandhu’s detractors have to say about the Bengali leader here. But it is worth a try reading the book. The book is, once again, quite a departure from works which usually flood the markets. Try reading it. You might end up liking it.

Bangabandhu, Rajniti O Proshashon

Bangabandhu Parishad

Bangabandhu Parishad has been an intellectual forum for the Awami League or, more appropriately, its followers. As such, this work is in its totality a collection of essays from a wide range of individuals on the diverse aspects of Bangabandhu’s politics and administration. Obviously, the write-ups are appreciative of Mujib’s positions on the various issues he faced. You may not agree with everything, but you surely will get the drift of what the Father of the Nation tried to achieve during the brief three and a half years he was in power.

For anyone who cares to go into the nature of the policies Bangabandhu’s government pursued between 1972 and 1975, this can truly be regarded as a notable point of reference.

Ekatturer Muktijuddho Roktakto, Moddho August O Shorhojontrer November

Col. (retd) Shafayat Jamil

(with Shumon Kaiser)

Shahitya Prokash

The book makes intensely sad reading. Shafayet Jamil was a key player in the dramatic events that were to unfold in November 1975. As part of the team led by Khaled Musharraf to reclaim the state from the predators who had commandeered it barely three months earlier, he was instrumental in forcing Khondokar Moshtaq to resign and the killers of Bangabandhu and the four national leaders to quit Bangabhavan.

This is an exciting book, covering as it does three events. There is the history, in however brief a fashion, of the war of liberation. That is followed by a comprehensive discussion of the tragedy of August 1975. And then, of course, comes an explication of the incidents and events leading from 3 November to 7 November 1975. Jamil is a survivor, a fortunate one. All the other leading figures of the Musharraf-led coup perished in the counter-coup spearheaded by Colonel Abu Taher. Ziaur Rahman emerged as the eventual beneficiary, with such disastrous results.

It is truly a gripping work and ought to be on shelves at home and in libraries.

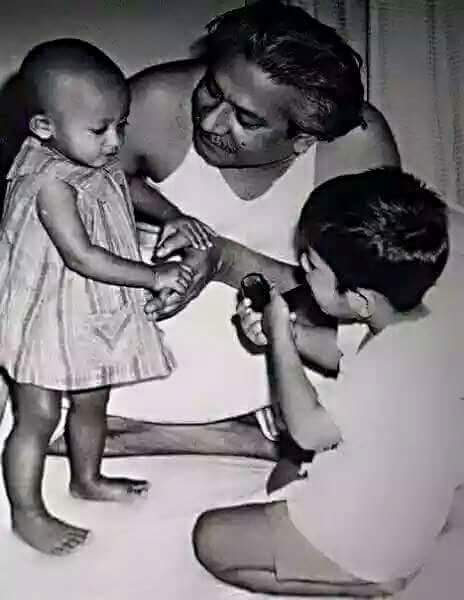

Father of the Nation

Bangabandhu Memorial Trust

An admirable album of photographs and images of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, beginning with his schooldays and ending with the end of his life in August 1975. The pictures are interspersed with quotes from the Father of the Nation, all expressive of his thoughts regarding the course Bangladesh should be taking on its journey to the future.

Copies just might yet be had at Bangabandhu Memorial Museum on Dhanmondi 32, the spot that is today part of Bangladesh’s history — of its glories, of its dark tragedies. The images evoke a sense of wonder about the past. It also causes huge sadness to well up in your heart.

Ekatturer 26 March

Bangabandhur Shadhinota Ghoshona

Mohammad Shahjahan

Bangla Prokashoni

Mohammad Shahjahan’s focus, as the title of the book makes clear, is on the events surrounding the declaration of independence in March 1971. With various quarters trying to stir up controversy over what actually happened on 26 March and especially with the rightwing attempting to build up Ziaur Rahman as the man who formally announced the country’s independence, the author presents the facts he thinks settle the issue once and for all.

Shahjahan comes forth with documents, with news reports of the period in question and thus adds substance to his assertion (one that is shared by millions across the country) that Bangabandhu did indeed send out the message of freedom to the country before he was taken into custody by the Pakistan army in the early hours of 26 March 1971.

It is a good read. It makes perspectives pretty clear.

Geneva-e Bangabandhu

Abdul Matin

Radical Asia Publications

Once again it is Abdul Matin, this time with an account of Bangabandhu’s stay in Geneva following surgery in London in mid 1972. The Father of the Nation was in a state of convalescence in Switzerland, but that did not deter him from meeting any and every Bengali who came calling on him. Matin provides a fascinating account of all the men and matters that came to Bangabandhu’s attention during that time — the genuine ones, the insidious ones and the plain hangers on.

And, by the way, you just might get a peek into things that were to worsen things for Bangabandhu in the years ahead. It is always good to go back to matters that in hindsight should have alerted everyone to what was about to happen.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

Sharokgrantha

Jyotsna Publishers

This is a rich collection of articles on the life and achievements of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It comes in three volumes and brings together a rich assortment of ideas from diverse personalities, all of whom are united by a common position on the 1971 war of liberation and the ideals set by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman through the 1960s and 1970s.

The volumes, in an overall sense, testify to the many facets of the Mujib character, those that have always made him stand out in the crowd and stand apart from his contemporaries. You really must appreciate the endeavour of those behind the compilations.

Bangabandhu O Muktijuddho

Amir Hossain

Adorn Publication

Bangabandhu was in solitary confinement in Pakistan during the entire course of the war of liberation. And yet there has never been any question that he had thoroughly prepared the Bengali nation for the imminent struggle for freedom. It was a remarkable point in history that the war of liberation was waged by the Mujibnagar government in Bangabandhu’s name.

In this well researched work, Amir Hossain brings a whole range of ideas into focus to explain the role that Bangabandhu played in the making of Bangladesh’s history. Anyone ready to study Mujib’s place in history will surely benefit from this work.

Bangladesh,The Unfinished Revolution

Lawrence Lifschultz

Zed Press

The work comes in two segments. Lifschultz dwells at considerable length on Colonel Abu Taher and his ultimate end on the gallows in one. In the other, his subject is the personality and government of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the difficulties it came up against and the conspiracies which proved to be its undoing. Lifschultz writes with considerable bravery, which is again natural considering his status as a foreigner. He focuses on a number of salient points about the coup of August 1975 and while doing so points the finger at foreign governments he suspects clearly knew, if they did not exactly take part, in the programme to eliminate Bangladesh’s founder.

Sadly, though, the work has run out of print. Not even the internet has any idea about it. But it remains a seminal work on the Bangladesh revolution, an unfinished one, as the author suggests. One could not possibly disagree with his assessment.

The Trial of Henry Kissinger

Christopher Hitchens

Verso

This surely is an acclaimed book, not least because Hitchens has made a reputation for himself as a plain-speaking writer. The work is divided into several chapters, the better to explain the nature of Henry Kissinger’s sinister policies in places as diverse as Chile and Bangladesh. Where the matter is one of Bangabandhu’s assassination, Hitchens leaves little doubt that the American establishment knew all about it before it happened. He comes down hard on then US ambassador to Bangladesh, Davis Eugene Boster (he misspells the name as Booster).

The bigger significance of the work is the author’s focus on Kissinger’s deep hatred for Bangladesh, a nation that had the audacity to break away from the American client state of Pakistan. Kissinger snubbed Mujib in Washington by not being present at the White House meeting between the Bengali leader and President Ford, but a short while later he sought to make amends, by visiting Dhaka and calling on Bangabandhu and holding a sham of a news conference. It is a revealing book, a collector’s item.

Ponchattorer Roktokhoron

Major Rafiqul Islam psc

Afsar Brothers

Rafiqul Islam’s book traces the entire history of the conspiracy that lay at the root of what happened on 15 August 1975. He names names and is often surprised that the very men who worked diligently for Pakistan in the days of rising Bengali nationalism or even after Bangladesh declared its independence in late March 1971 were chosen by Bangabandhu to be near him, and literally at that.

It was these very men who destroyed the Father of the Nation. The sadness is in the thought that he did not recognize them for the villains they were.

Who Killed Mujib?

A.L. Khatib

Vikas Publishing House

One of the earliest books on the tragedy of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (the work was published in 1981), it explores the wide network of conspiracy that was to take the life of the Father of the Nation in 1975. A.L. Khatib, a prominent journalist with roots in Sri Lanka but based for the better part of his career in the South Asian subcontinent, brings out some intricate details of the plans shaped to do away with Bangabandhu. The criticism is there that the book was written in haste. Perhaps, but what certainly is of importance is that there is hardly any instance Khatib cites about the tragedy that one can be dismissive of. A whole range of characters people the book. Apart from Bangabandhu, there are all the other characters, notably the ‘little sparrow of a man’ that was Khondokar Moshtaq as also the political figures who constantly used to be around Mujib but at dawn on 15 August were found in the usurper’s company. The author dwells in fascinating detail on the conspiracy that went on at the Bangladesh Academy for Rural Development (BARD) in Comilla, the presence there of Moshtaq and others with distinctly pro-Pakistan leanings. You read the book and as you do so, you realise just how closer to doom Bangabandhu was getting to be every day.

Copies of the work are obviously not available. That is a pity, for it deprives many of the chance of arriving at truths that the Mujib government was blissfully unaware of in those darkening days of conspiracy.

A witness of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman assassination case has said in his statement that convicts Bazlul Huda and Noor Chowdhury shot Bangabandhu with Sten guns on August 15, 1975.

A witness of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman assassination case has said in his statement that convicts Bazlul Huda and Noor Chowdhury shot Bangabandhu with Sten guns on August 15, 1975.