SHEIKH MUJIB: TRIUMPH AND TRAGEDY

bangabandhu

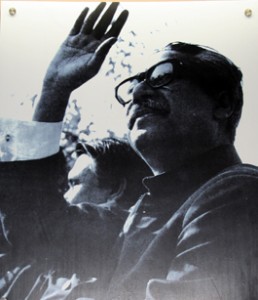

This, surprisingly, is the first biography in English of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the founder of Bangladesh, even though more 30 years have passed since he was assassinated in a bloody military coup on August 15, 1975. Known to most Bangladeshis as Bangabandhu, or friend of Bengal, a title bestowed on him by acclamation in a mammoth public meeting in Dhaka on 22 February, 1969, he was truly a man of the people, someone who had made the cause of his countrymen and women his own through endless trials and tribulations. And yet he had been assassinated in the country he had championed ceaselessly soon after it became independent. Also, he had disillusioned quite a few people in record time in governing it. How did he win the hearts of his people as “the father of the nation” and secure a place in their history as Gandhi did in India or Jinnah did in Pakistan? What caused him to slide in their esteem? But also, what was he like as a human being as well as a leader? And now that three decades have passed since his death, is it possible to arrive at a real estimate of the man and his achievements?

It is to S. A. Karim’s credit that he has tried to raise these questions implicitly and explicitly and answer them succinctly and objectively in his biography, Sheikh Mujib: Triumph and Tragedy. Drawing on published sources, a few interviews with people who knew Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, his own encounters with him as the first Foreign Secretary of independent Bangladesh, Karim has striven to give a balanced, accurate, and thoughtful portrait of the man. His conclusion is that he was a leader whose triumph was on a heroic scale but whose ending was, at the very least, tragic.

Karim begin his biography by providing us with the background to Mujib’s rise to fame, the partition of India, and the rise of the Muslim League. He was barely twenty years old in 1941 when he first encountered Fazlul Haq, the Chief Minister of Bengal, and more importantly, Shahid Suhrawardy, the Minister of Commerce, when they visited Mujib’s hometown Gopalganj, then in the district of Faridpur, for a public meeting. He was immediately drawn to Suhrawardy’s brand of politics and Kolkata, where he became a student of Islamia College. Here he began to attract attention as a Muslim League activist, working indefatigably to rally Muslim students of the region to work for Suhrawardy’s faction of the party, which, ultimately, joined the movement for Pakistan. After partition, Mujib relocated to Dhaka, but found himself becoming increasingly alienated from the conservative politicians of the Muslim League who had arrogated power in East Pakistan. Inevitably, he became involved in the movement to establish Bengali as a state language of Pakistan, and the movement in turn led to the creation of the Awami Muslim League. Courting arrest repeatedly, and resorting to hunger strikes time and again when in prison, Mujib immediately became prominent in East Pakistan because of his continuous and principled opposition to the communal and feudal politics of the Muslim League. In quick time, he became the General Secretary of the increasingly secular Awami League (it dropped “Muslim” from its name in 1955), and a minister of the United Front government that drove the Muslim League from power in the provincial elections of 1954.

From this point onwards, there was no stopping Mujib, except by confinement in jail. As Pakistani politics more and more became the preserve of the military, as the military conspired with a few West and East Pakistani politicians and bureaucrats to deprive Pakistan of democracy, and as the numerically superior Bengalis of East Pakistan found themselves increasingly thrust out of power, Mujib was in the thick of the action to wrest back the rights of his people through a secular, organized, and democratic movement, even as a succession of military generals attempted to rule Pakistan through martial law. In and out of jail in the latter half of the 1950s and throughout the 1960s, Mujib became convinced that Pakistan was a dead end for his people and that a way out of the clutches of the military-bureaucratic coalition that was ruling Pakistan at this time was needed urgently.

In his desperation, Mujib even thought of seeking the help of India. Karim suggests that it could have been his admiration for Subhas Bose that led Mujib to take a secret trip to Agartala in January 1963 where he met Satindranath Sinha, the Chief Minister of Tripura, to see if Indian assistance would be forthcoming for a separatist movement. But according to Sinha, whom Karim quotes without citing the source, Nehru was not interested and the trip was inconsequential. It is ironic, then, that it was for a trip to Agartola that he never took that the Pakistani government would try him for treason in what has come to be known as the Agartola Conspiracy case in 1967. Unfortunately for them, the effort at concocting a conspiracy backfired, for not only were they unable to sustain their case in front of the special tribunal that was set up for the purpose, they were also forced to release Mujib in the face of increasingly violent agitation against them in both wings of Pakistan. Indeed, the Pakistani dictator of the period, Ayub Khan, was forced to resign, and Mujib left the jail triumphantly in 22 February 1969, widely acknowledged by this time in his part of Pakistan as the man most suited to lead it forward to autonomy and prosperity.

The next two years saw Mujib at his best: inspiring his people through fiery speeches in countless meetings, seemingly inexhaustible energy, and an indomitable will. He kept highlighting his party’s demand for complete autonomy in East Pakistan until the message went home: in the elections held in December, 1970, the Awami League won 167 of the 169 seats in the province. But Mujib, committed to negotiations through democratic channels, was mistaken in his assumption that the Pakistani generals and Zulfiquer Bhutto, the clear winner in West Pakistan, were going to hand over power to his party merely because it had a clear majority when it was bent on getting the maximum autonomy conceivable for East Pakistanis.

In fact, Yahya Khan, the general who replaced Ayub Khan, colluded with Bhutto to postpone the March 3, 1971 opening of the National Assembly. The result was a spontaneous and angry civil disobedience movement in East Pakistan which, in effect, negated the Pakistani state, making Mujib the de facto ruler of East Pakistan. As if to show that he was worthy of the part, Mujib gave what is undoubtedly his finest speech to his people on 7 March, stopping just short of independence, but claiming self-rule in almost all matters. Yahya Khan’s response, once again was to scheme with Bhutto, and make a show of negotiations, bent as they were on keeping West Pakistan dominant in deciding the future of Pakistan. And so Mujib and his party kept negotiating with Yahya and Bhutto in good faith, even as the Pakistani army prepared themselves for a crackdown that would decisively and brutally neutralize Mujib and his party and ensure perpetuation of their hegemonic rule.

The date in which the Pakistani army moved to destroy Mujib and thwart the Bengali desire for complete autonomy was the night of March 25. As far as Karim is concerned, Mujib and his party leaders had “ignored signs of the gathering storm” and thus an unsuspecting, unprepared people were brutalized, the movement for autonomy stunned, and Mujib himself captured. Here again Karim is critical of Mujib’s decision to let himself be arrested to deflect the Pakistan army from wrecking havoc in his country, Mujib, reportedly, told his followers who wanted him to flee, “If I leave my house (Pakistani) raiders are going to massacre the people of Dhaka. I don’t want my people to be killed on my account”, but his decision did not prevent genocide; on the contrary, it exposed his people to the wrath of the Pakistan army.

While the Pakistani army went on the rampage, Mujib himself was taken to prisons in West Pakistan where he underwent a trial at the end of which he was found guilty of trying to break up Pakistan and was awarded the sentence of death by hanging. Meanwhile, Bengali troops who had defected, political activists of various parties, and students and refugees who had fled to India came together to organize a guerilla campaign against the Pakistani army and to launch a war that would liberate their country. Inevitably, India was drawn into the conflict, and on December 16, 1971, the Pakistani army in East Pakistan surrendered in Dhaka to the combined Indian and Bangladesh forces. This was how Bangladesh was born after nine blood-soaked months. With the Pakistani army in disgrace, and Bhutto calling the cards, and in the face of international pressure, Mujib was released from jail and flown back to Dhaka via London in a RAF plane on 9 January 1972.

Mujib’s homecoming marked the most triumphant moment of his career as a politician who had worked steadfastly and whole-heartedly for his people. But the next few years saw him sliding in popularity and having a torrid time coping with the innumerable problems facing a poor nation that had been denuded for over two decades by the West Pakistanis and that had hemorrhaged steadily for nine months. The prescriptions that he got from his advisers in the Planning Commission, inclement weather conditions that led to a terrible famine in 1974, rising global oil prices, growing lawlessness, his unwillingness or disinclination to be firm with party men and women and relatives who were clamoring for benefits and sinecures, underground movements that appeared to be gathering momentum and threatening the state, all appeared to conspire to show Mujib as unable to cope with the responsibility of steering a nation from political independence to peace, stability, and prosperity.

The stage was set, in other words, for triumph to turn into tragedy. The man who had staked his life repeatedly for democracy now attempted to create a one party state, proscribe newspapers, and stifle dissent. A radical leader died mysteriously while in police custody. Members of Mujib’s extended family suddenly began to assume more and more power. People who had shown total devotion to him and Bangladesh like Tajuddin Ahmed was dropped and sycophants were promoted to important positions. The air in Dhaka was rife with rumors of conspiracies and coups but Mujib chose to ignore them, convinced that the people he loved and had been ready to die for would never harbor conspirators against him. And so it was that he rendered himself completely vulnerable and was murdered by some adventurous, resentful, and ambitious military men in the early hours of August 15, 1975.

Karim’s verdict on Mujib’s rise to fame and the darkening world in which he died and his assessment of his subject’s personality, career and contribution to Bangladesh is surely sound. His Mujib is a gracious and compassionate person, generous almost to a fault. His love for his people and willingness to sacrifice himself for them is never in doubt. He had more or less “single-handedly” spearheaded the movement for Bangladesh in its climactic phase and until his incarceration in 1971. And he had struggled to cope with extremely difficult situations the best he could till desperation forced him to adopt undemocratic measures. He was, in short, a “tragic hero” flawed and yet great and even grand.

S. A, Karim’s Sheikh Mujib: Triumph and Tragedy seems to have been written at leisure; the consequence is that it is even-paced, well-organized and sedate. He strives to be balanced and objective in his presentation and he writes out of a conviction that as a biographer he must be committed to presenting his subject truthfully and adequately. He has also tried to come up with a book that will be read by many and to that end he has decided not to overload it with “notes and references”.

It must be said though that Karim’s book is not the “comprehensive biography” he claims it to be in his Preface. For one thing, he spends far too much time sketching in the background and often loses sight of his subject in dealing with the historical contexts. At times, a few chapters might go by without any reference to Mujib and in scores of chapters he makes only a fleeting appearance. Indeed, one may occasionally even be mislead into thinking that one is reading a political history of Bangladesh where Mujib is the main actor and not his biography. Moreover, Karim appears to have not realized that a biographer’s task includes looking at archival material and contemporary newspaper reports and tracking down unpublished written sources as well as perusing published books and documents. He could have, for example, tried to include excerpts from the many speeches Mujib gave on public occasions that have been surely recorded in parliamentary proceedings; talked to his admirers, tracked his path to power doggedly instead of spending most of his time giving sketches of the political history of East Pakistan.

But what appears to be the singular defect of this biography is Karim’s reluctance to imagine himself into positions, crises and situations Mujib had to negotiate or to come close to his subject through what Keats had once characterized as “negative capability”. In his introduction to his incomparable biography of Samuel Johnson, James Boswell had claimed that the “more perfect mode of writing any man’s life” involved “not only relating all the most important events of it in order, but interweaving” it with the subject’s words and thought till “mankind are enabled to see him live”. In his conclusion, too, Boswell had felt with satisfaction that in his book the character of the great man had been “so developed “in the course of his work “that those who have honored it with a perusal, may be considered as well acquainted with him”. Karim follows Mujib from a great distance and almost never allows him to speak for himself. There is little or no effort to see Mujib from up close and there is definitely no attempt to get into his mind. The result is a biography that does not make us “see him live” and think and feel and this is a pity for by all accounts Mujib was a passionate, loving and caring man. Karim tries to make a virtue out of detachment and objectivity not realizing that what he needed to do was creatively represent the thoughts and emotions of a man who was overpowering because of his love for his people and conviction about what was right for them.

Nevertheless, there is a lot to be thankful for in Karim’s Sheikh Mujib: Triumph and Tragedy. At the very least, a sensible effort has been made to present the life of a great and generous even if flawed leader; surely others will now follow to give us a more intimate, imaginative, intensely realized and fuller portrait of the father of Bangladesh and the friend of all Bengalis everywhere. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman deserves no less!

Author : S. A. Karim.

The University Press Limited, 2005. pp. 407, Tk. 500.00 ISBN 984 05 1737 6

Fakrul Alam is on leave from the University of Dhaka and now teaches English at East West University, Bangladesh.