He is our claim on history

On a cold November night in Delhi a little over a decade ago, the respected Indian journalist Nikhil Chakravartty mused on the human qualities in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He and Mujib, Chakravartty told me, had known each other in Calcutta in the dying days of a united India. After August 1947, though, the two had parted ways out of sheer political compulsions, naturally. Mujib was to go on to build his political career in East Pakistan and obviously lost all contact with Chakravartty, who for his part went into journalism and kept trace of what the East Bengali was doing in his new country.

On a cold November night in Delhi a little over a decade ago, the respected Indian journalist Nikhil Chakravartty mused on the human qualities in Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He and Mujib, Chakravartty told me, had known each other in Calcutta in the dying days of a united India. After August 1947, though, the two had parted ways out of sheer political compulsions, naturally. Mujib was to go on to build his political career in East Pakistan and obviously lost all contact with Chakravartty, who for his part went into journalism and kept trace of what the East Bengali was doing in his new country.

The two men were not to meet again till January 1972, when Mujib, by then the founder of the independent People’ Republic of Bangladesh, called his first news conference after his return from captivity in Pakistan. As Chakravartty related the tale to me, it all sounded familiar, for I had gone through a similar experience with Bangabandhu. Chakravartty was seated at the end of the room, one among a crowd of media people come to interact with the Bengali leader for the first time after his homecoming. Bangabandhu soon entered the room, took in the view and at one point focused his gaze on Chakravartty. “Tumi Nikhil, na (aren’t you Nikhil)?” he asked. Chakravartty was immensely surprised and asked Mujib if he could recognize him after all those years. Mujib laughed and gathered Chakravartty to him in the kind of embrace he always had for friends and admirers.

Here, then, is an insight into the human aspects of the Mujib persona. As a high school student in Quetta, I met Bangabandhu in July 1970, the obvious purpose being to have his signature affixed in my autograph book. In April 1972, when I visited Ganobhavan, the old President’s House at Ramna (some days were open house for citizens to see the Father of the Nation) to tell him about my worries relating to the abolition of English medium education in the country (with English medium education gone, I could not hope to finish school), I was nearly literally stunned to discover that he remembered having met me in distant Baluchistan.

He asked about my parents, wanted to know if they and the rest of the family were alive. It was quintessential Bangabandhu. In subsequent times, through conversations with people of my father’s generation and through the reminiscences of others, I was able to understand the nature of the immeasurably large soul that was in the Father of the Nation. He remembered faces long years after he had come across them in his travels through the hamlets and villages of Bangladesh. More poignantly, he could tick off the names of people he was meeting after years, even decades. Not many individuals you know, and least of all politicians, possess that capacity for remembering. Bangabandhu seemed to know almost everyone in the country. That was the nature of the man. And that was not all. There was a spontaneity of emotions in Mujib that he never sought to paper over with make-believe urbanity. He laughed uproariously and made little effort to foist any diplomatic or political restrictions on his natural way of looking at things.

Watch any of the old photographs of the great leader, observe the twinkle in his eyes and the laughter that has been arrested by the lens of the photographer for posterity. When Abdus Samad Achakzai, meeting him after a long span of years, remarked that the Awami League chief had grown old, Mujib shot back: “Ayub Khan ne tum ko bhi buddha bana diya, hum ko bhi buddha bana diya (Ayub Khan has made you old and he has made me old as well).” Then he broke into a guffaw, laughter that convinced everyone around that here was a national politician to whom protocol was of little consequence. If protocol were important, he would not have lived and died at his Dhanmondi home.

One of the greatest qualities in Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was the abundance of confidence on which he based his life and politics. In the early days of his trial in the Agartala conspiracy case, he cheerfully told a western journalist in court: “You know, they can’t keep me here for more than six months.” He was proved almost right, arithmetically speaking. He was freed seven months after he had made that statement. It was a time when the full force of the Pakistani establishment had come down on him, but that did little to deter him from speaking his mind.

When a Bengali journalist he knew well studiously tried to avoid being seen talking to him on the first day of the Agartala trial, Mujib exclaimed, loud enough for everyone present in court to hear: “Anyone who wants to live in Bangladesh will have to talk to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.” Note the courage. Note too the use of the term “Bangladesh.” His dream of national freedom was already taking shape in the recesses of his political being. By November 1969, he was telling people that East Pakistan would thenceforth be known as Bangladesh. He was not willing, not under any circumstances, to compromise on the issue.

And that was one of the finest traits in his character. Once he had decided on a course of action, he was not ready to consider any deviation or change or readjustment. Back in 1957, he asked a plainly sleepy Husseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy if it would not be a reasonably good proposition to take Bengalis out of the state of Pakistan. One can imagine the shock that must have gone through Suhrawardy, the man who had only a year earlier assured Bengalis that the 1956 constitution had guaranteed ninety eight per cent autonomy to East Pakistan. Of course it was no such thing. The point, though, was that Suhrawardy could not conceive of the end of Pakistan in the land of the Bengalis. On the other hand, Mujib was already thinking of a post-Pakistan condition for his people. In the decisive period of early March 1971, it was a nationalistic yet circumspect Mujib who told the media: “Independence? No, not yet.” He was already moving toward his goal, but he was at the same time making sure that his adversaries, in this instance the Yahya Khan junta and Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, were given enough rope to hang themselves. In the early moments of 26 March, he had no more illusions about the course Bengalis needed to take. His message of freedom was passed on to M.A. Hannan in Chittagong, minutes before he was taken into custody by the Pakistan army.

Mujib’s resilience was sorely tested in Lyallpur, where he was brought before a military tribunal for trial on charges of waging war against Pakistan. He did not recognize the court and refused to accept the lawyer, A.K. Brohi, appointed for him by the junta. Held incommunicado, with no access to newspapers or radio or visitors, he made sure that his steely individuality did not collapse. He was too strong in his physical and psychological make-up to break down. Throughout his long political career, he wore down his tormentors, every single one of them. His determined politics ended the presidency of Ayub Khan. And it was his undisputed, focused leadership of the Bengali nation which, despite his incarceration a thousand miles away from home, ripped Pakistan apart and left Yahya Khan, Bhutto and everyone else among his enemies biting the dust.

In February 1974, on arrival at Lahore for the Islamic summit, Bangabandhu knew his triumph over the state of Pakistan was complete. When Prime Minister Bhutto introduced him to Tikka Khan, by then chief of staff of the Pakistan army, Mujib had a curious, almost sarcastic smile playing on his lips. As Tikka saluted him, Bangladesh’s founding father remarked, simply: “Hello, Tikka,” and moved on. History had come full circle. In March 1971, when his soldiers had informed Tikka that they had Mujib in the cage and asked him if the Bengali leader should be brought before him, the Butcher of Bengal (and, earlier, Baluchistan) had replied contemptuously: “I don’t want to see his face.” In Lahore barely three years later, the man with that face was before him, and he was paying homage to him in full view of the world.

You can go on speaking of Bangabandhu for an eternity. Yes, he had his foibles. There were the many peccadilloes he could have done without. But there was the big man subsisting in his soul. He bestrode the world as our very own, a colossus. Fidel Castro marvelled at the fact that Bengalis had liberated themselves in his name despite his imprisonment in enemy land. Anwar Sadat referred to him as Brother Mujib. Some years ago, when I chanced upon Edward Heath in London and told him where I was from, he paused, smiled and said softly: “Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s country.” That was a measure of the historical niche Mujib had carved for himself. It was history he created when he spoke before the United Nations General Assembly in his native Bengali. It made the tears run down the cheeks of an Indian diplomat, a Bengali, who ran up to Bangabandhu and hugged him from sheer gratitude.

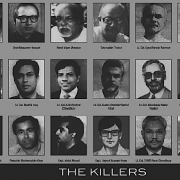

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains our authentic claim on history. We went to war in his name, prayed for him in the darkest days of our national life. When he died, the light went out of our lives and the wolves took over. Our failure to save the man who had always been our saviour, our pusillanimity in the face of thuggishness and murder, on August 15, 1975 remains a shame that hangs like an albatross around our necks. We bear the cross, and will do so until we can redeem ourselves through travelling back to the principles Bangabandhu held dear — and which we upheld under his inspirational leadership. Joi Bangla will then be sounded all over the land once more; and the dream of Shonar Bangla will be retrieved from the debris of time, to shape rainbows once again for the huddled masses the Father of the Nation spoke for.

Author : Syed Badrul Ahsan, Executive Editor, Dhaka Courier .