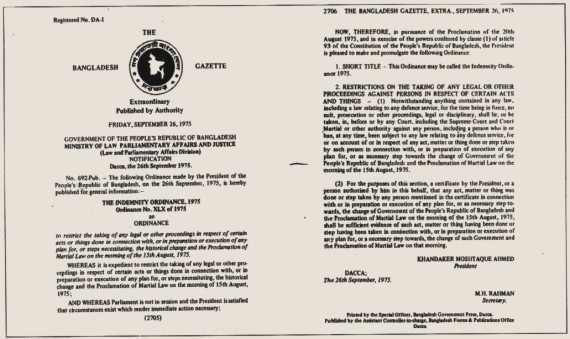

The Indemnity Ordinance of 1975 which protected the killers from legal action

This past week has been one of celebration. The news media have provided rigorous coverage. The people have expressed their gratitude through milad mehfils and other occasions of thanksgiving. Most surprisingly and significantly, our political parties have, for once, agreed on something.

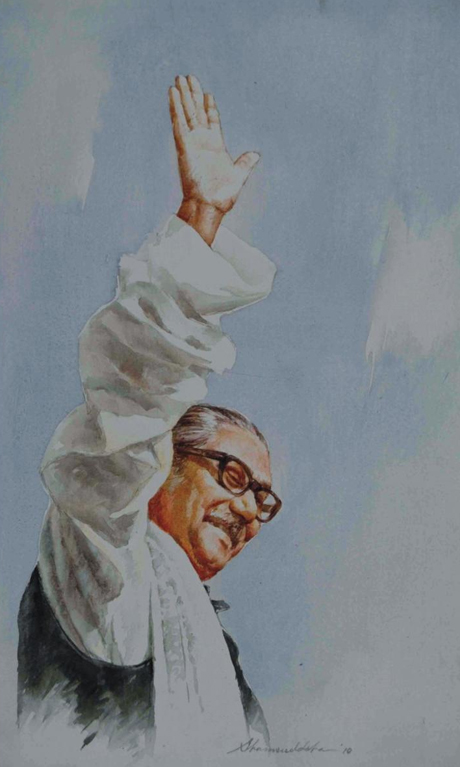

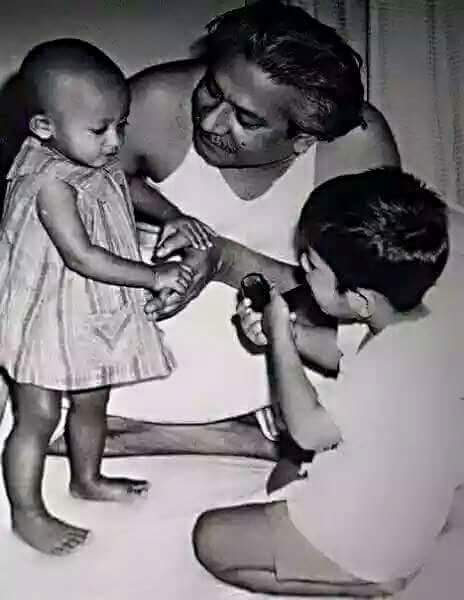

No one can deny that justice had to be done in the case of the killing of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and 21 members of his family and household, including children and pregnant women. Yet, this very justice was denied by everyone who ever had the power to do anything about it. According to legal experts, in most of the political killings in our history, a part of the State was involved, for which reason it was difficult for the other parts to take action against them and thus have the legitimacy of their own power questioned.

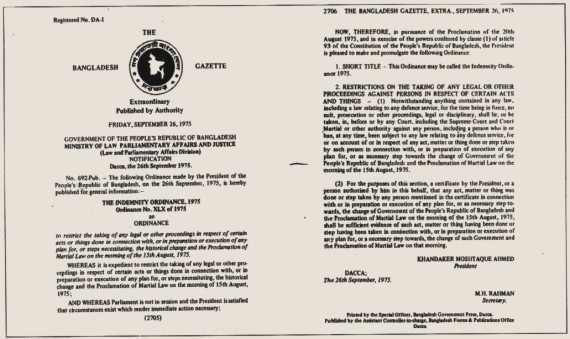

Those who came to power after the killings on August 15, 1975 are said to have been the beneficiaries of the crime and so, naturally, they were not the ones bearing placards demanding justice. On the contrary, in September 1975, the government under President Khandaker Mostaque Ahmed promulgated the Indemnity Ordinance which restricted ‘the taking of any legal or other proceedings in respect of certain acts or things done in connection with, or in preparation of execution of any plan for, or steps necessitating, the historical change and the proclamation of Martial Law on the morning of the 15th August, 1975’. The ordinance, which basically prevented anyone from taking legal action in the case, was later legalised in parliament. There was no scope even to question the immorality of the act, which essentially barred the process of justice.

‘The case of Bangabandhu is an emblematic one,’ says Barrister Sara Hossain of the Supreme Court. ‘It marks the perversion of the court of justice. Not only was justice not done, but it was made impossible to take any legal action by the promulgation of the Indemnity Ordinance, because of which law enforcement officials refused to take any case pertaining to the crime.’

No successive government, military or democratic, took any steps to repeal the Indemnity Ordinance of 1975 or try the killers of the Father of the Nation. The culprits roamed free and even took credit for their crimes. In an interview with the Sunday Times on May 30, 1976, Syed Farook Rahman, said to be the mastermind behind the killings, said, “Let the Bangladesh government put me on trial for the assassination of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. I say it was an act of national liberation. Let them publicly call it a crime.” He even cited five reasons for which he “ordered” Mujib’s killing. When the killers were finally forced to face up to their crimes, however, albeit 21 years later, the bravado faded. Despite all the evidence to the contrary, they denied responsibility.

The chain of reactions which Farook and his accomplices set in motion did not end there. The struggle for power, the coups and counter-coups and killings continued, so much so that veteran journalist Anthony Mascarenhas, who followed the liberation struggle of Bangladesh and the chaotic years which followed, has termed it Bangladesh’s “legacy of blood”, beginning from the partially flawed leadership of Sheikh Mujib which set off the killings in the first place. The same killers who on August 15, 1975 murdered Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family, also assassinated four national leaders — Syed Nazrul Islam, acting president of the government-in-exile, prime minister Tajuddin Ahmed, finance minister M Mansur Ali and minister for home affairs, relief and rehabilitation AHM Qamruzzaman — inside a prison cell, on November 3, 1975. The latter massacre was a part of a contingency plan in the event that a counter-coup occurred, basically, to wipe out a whole leadership whom the killers did not see fit to govern the nation.

On May 30, 1981, President Ziaur Rahman, who ultimately came to power after the coups and counter-coups of the 1970s, was assassinated by a faction of army officers, in approximately the 20th coup attempt against Zia himself. The killing of Brigadier Khalid Musharraf, Colonels Huda and Haider in November 1975, as well as the execution of Col. Abu Taher by Zia and the hasty trial and punishment of Zia’s own killers, were also said to be politically motivated.

Political violence and assassinations in order to eliminate opposition and rise to power have spilled over into our recent history. Some have wiped out a whole leadership. Others have stifled opposition and thwarted differences. The killing of Salim and Delwar, Raufun Basunia and Nur Hossain, among others, during the Ershad era; the bomb blast at a Communist Party of Bangladesh (CPB) meeting in 2001 which killed seven people and injured over a hundred; the killing of Jatiyo Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) leader and freedom fighter Kazi Aref in 1999 and the violent deaths of Awami League (AL) leaders Mumtazuddin Ahmed and Manzurul Imam in 2003 and AL lawmaker Ahsanullah Master in 2004; the 23 people killed in the August 21 grenade attacks and the killing of former finance minister SAMS Kibria only six months later — the cases are endless, but justice has been served in few.

In the case of the killers of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his family, not only were they not punished for their crimes, but they were actually allowed to escape and even rewarded by the State with positions of prominence such as diplomatic postings abroad. ‘This gave the message that you can commit the worst crimes, commit them openly, revel in them and not only will you be excused but you will be glorified,’ says Barrister Sara Hossain. ‘This verdict overturned that idea and set in motion the important and powerful wheels of justice.’

According to Sultana Kamal, human rights activist and advocate of the Supreme Court, it is unfortunate that the crimes were tolerated for as long as they were. ‘Justice delayed is justice denied,’ she says, ‘but at least we ultimately got justice. Ideally, the trial should have begun immediately after the events occurred.’ The delay in justice has set a trend in our culture where no human rights or legal issue is seen objectively, says Kamal. ‘Everything is coloured along political lines.’ ‘It wasn’t the AL’s duty alone to try the perpetrators,’ says Sultana Kamal, ‘it was a national duty. But this was not done.’

But it was only when Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s party, the Awami League, headed by his daughter, Sheikh Hasina, came to power in 1996 that the Indemnity Ordinance of 1975 was repealed and the process of justice initiated. A murder case was filed in October of that year by a member of Sheikh Mujib’s staff at the time who had delayed the action all those years for fear for his life. In November 1998, 15 army personnel were handed down the death sentence in a trial court, of which 12 of the death sentences were upheld by the High Court in April 2001. The convicted were: Syed Farook Rahman, Bazlul Huda, Shahriar Rashid Khan, Mohiuddin Ahmed, AKM Mohiuddin Ahmed, Khandaker Abdur Rashid, Shariful Haque Dalim, AM Rashed Chowdhury, SHMB Noor Chowdhury, Abdul Mazed and Risaldar Moslehuddin Khan. The first five were in custody and later appealed the verdict. The latter seven were absconding and are currently rumoured to be moving between countries like the US, Canada, Libya, Pakistan and Kenya.

The process was again stalled during the rule of the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP)-led coalition government from 2001 to 2006. Further delays were caused by judges frequently embarrassed to hear the case, thus avoiding their responsibilities. In September 2007, during the reign of the caretaker government, a three-member Appellate Division bench allowed five of the convicted to appeal the High Court order. The hearings began last month. Last week, the long-awaited verdict rejecting the appeals and upholding the death sentences of all 12 of the convicted was announced. The execution process has begun, while the verdict is under review and will be carried out following the presentation of a mercy petition to the president. For those who have been absconding and did not appeal the High Court verdict, steps will be taken to find and bring them home.

It has been difficult getting this to happen, says Barrister Sara Hossain. ‘In the years between the start and end of the trial, not only was nothing done but the process was actually blocked.’ Following the verdict, the law minister during the time of the BNP-led coalition rule and currently a standing committee member of the party, Barrister Moudud Ahmed, said that the nation ‘heaved a sigh of relief at the verdict’. The Jatiya Party said that it was a major step forward in the establishment of rule of law in the country. The Jamaat-e-Islami, a member of the BNP’s four-party alliance, declared its respect for the judgement of the highest court. Yet all these parties and key political players did nothing to bring about this verdict or to even initiate the process during their tenure in government.

‘This is sheer hypocrisy,’ says Barrister Sara Hossain. ‘For five years when his party was in power and he was the law minister, Barrister Moudud Ahmed did nothing to take this case forward.’ The role of the highest level of the judiciary — even in the case of the murder of someone like Bangabandhu — contributed to the process, says Hossain. ‘The judges could have heard the cases but they were embarrassed.’ The AL in its first term began the trial proceedings, and now in its second term has seen the final judgement passed. If the AL never came to power, would justice never have been done?

As positive as this verdict may be, what does it say about the legal and judicial system of our country and the sense of justice in general? Will justice only prevail for those in power and will the system always sway along with the political circumstances? Will those who are faced by injustices every day never be vindicated unless they are politically powerful? If such high profile cases take over three decades to be resolved, what of those which do not even make news headlines?

‘This verdict is positive, but it is also chilling to think about the whole difficult process of it actualising,’ says Sara Hossain. ‘Despite a close family member being in the highest position of power, it took this long, which shows that even if you are powerful you may not get justice, unless you are actually in power. But at least we know that it can be done.’

Though personally opposed to the death penalty, Hossain says that the verdict is comforting and reason for hope. ‘Now we must look to the endless other cases of abuse and torture committed by the security forces. This judgement should allow us to stand up against such gross abuses. We must make the whole system accountable to everyone.’

The government’s promise to try the perpetrators of the jail killings, the August 21 massacre, the attack on SAMS Kibria and the BDR mutiny is encouraging. But let justice not be limited to those cases which only affect the party in power. The list of pending cases is long, dark and complex, starting from former president Ziaur Rahman’s killing, which the BNP itself, for whatever reason, failed to settle.

Trials are aimed to ensure justice, not to take revenge, says Sultana Kamal. ‘All the injustices in our country must be dealt with, including extrajudicial killings, the jail killings and the trial of war criminals. Let this verdict be an inspiration. It should come as a lesson to our people, which says that criminals cannot get away with impunity; sooner or later, perpetrators will be held accountable and punished for their crimes. If we learn from it, then this judgement will be an achievement.’

This judgement is indeed a historic one. It brings closure to a long drawn out and bloody chapter in our history, which had set the unfortunate precedent of killers getting away with impunity. It also sets in motion a long overdue process of healing of a brutalised national psyche. Let us hope that it is also the beginning of a new chapter of doing justice in all cases in our past and future, regardless of who holds power and who the beneficiaries are. The word justice is stripped of all partisanship and leanings and implies ‘the quality of being just’; let our justice system also be so.

Author – Kajalie Shehreen Islam

I call upon the people of Bangladesh, wherever you might be and whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh and final victory is achieved.”

I call upon the people of Bangladesh, wherever you might be and whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh and final victory is achieved.”