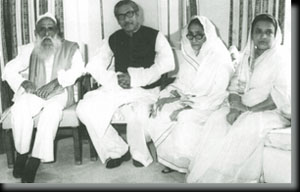

The atonement still goes on Bangabandhu with parents

When Bangabandhu was gunned down in the early hours on 15 August 1975, the Bengali nation to which he gave independence began a process of atonement for having committed patricide that continues even now. What can be crueler than killing the nation’s father that gave identity to a people who remained colonized for twenty-five years after the British had pulled out of the subcontinent in 1947?

When Bangabandhu was gunned down in the early hours on 15 August 1975, the Bengali nation to which he gave independence began a process of atonement for having committed patricide that continues even now. What can be crueler than killing the nation’s father that gave identity to a people who remained colonized for twenty-five years after the British had pulled out of the subcontinent in 1947?

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was a rare personality who is not born in every generation. It was because of his uncompromising and visionary political struggle for which Bengalis gained a homeland of their own, and it was also because of his unflinching courage to boldly face the persecution of the Pakistani leadership, Bengalis are today getting opportunities in all fronts to prosper and flourish. Why then was he so brutally killed, with all members of his family, only a few years after independence?

The assassination of Bangabandhu is similar to the fall of a tragic hero. Indeed he was a protagonist in the political stage of the subcontinent unparallel to any other politicians of his own and the previous generation. Tragic heroes cannot be ordinary men, they have to be Kings or Princes, and therefore no tragedy has been written after the 16th Century. This genre of literature flourished only during the 5th century BC in ancient Greece and the 16th Century AD in England and France. With the advent of democracy, tragedy retreated to the background because ordinary men could not be endowed with the unqualified greatness of tragic heroes.

Bangabandhu’s life is characterized by many of the traits of a tragic hero: his extraordinary personality, his greatness of heart and his awesome popularity were all like the strengths of a tragic hero. But did Bangabandhu have a tragic flaw that like Hamlet or King Lear ultimately transformed him to the victim of his own mistake? Banganbandhu is not a character of a Shakespearean play; he was a rare human being, a politician with an extraordinary caliber. However like Prince Hamlet, procrastination partly led him to his tragic fall. Yes, he delayed like the prince of Denmark; his first reluctance was to form a government of national unity immediately after his release from Pakistani prison. Later when he declared the establishment of the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BAKSAL), it was much too late, for the conspirators already had enough time to regroup and strike at an opportune moment to eliminate the towering man who had always outmaneuvered them in the past.

Bangabandhuhu’s second delay was his inability to summarily try and punish those who had killed, raped, burnt and looted in the soil of Bengal alongside the blood-drinking Pakistani military. Like King Lear, he did not realize that evil men could never change; those without compassion could never love humanity. The magnanimous Bangabandhu allowed the killers too much time to reorganize and strike back at him. Like Shakespeare’s King Lear, Bangabandhu also hurried. Lear the old King hastily banished and disinherited Cordelia his daughter who loved him the most. Bangabandhu in all his glory, only in his early 50s, decided to prematurely visit Pakistan at the behest of some Arab leaders. His sudden decision to attend the Organization of Islamic Conference (OIC) meeting in Lahore gave the conspirators a renewed opportunity of plotting to kill a man who had to be earlier spared because of international pressure. The crafty Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto had managed to secure the release of the 195 listed war criminals of the Pakistani military as an outcome of the Shimla agreement signed by Pakistan and India in 1973. Why then was the hurry and the necessity of returning to a country whose military, fully supported by Zulfiqar Bhutto, wanted the entire territory of Bangladesh to be smeared in blood only a couple of years ago in 1971? What could have Bangabandhu asked from Pakistan? His trip to the humbled Pakistan of 1971 can at best be described as the journey of a proud victor to the land of the vanquished. Little did he realize that behind the glitter and the razzmatazz surrounding his arrival at the Lahore airport, and his participation in the OIC meeting, a plot was underway to avenge the defeat in the hands of the Bengalis in 1971.

Lawrence Lifschultz, one of the most dispassionate chroniclers of the history of our glorious war of liberation, mentions in his book Bangladesh: the Unfinished Revolution the link of the infamous Inter Services Intelligence (ISI) of Pakistan in the murder of Bangabandhu. The ISI mustered support of a few disgruntled soldiers of the Bangladesh Army and successfully carried out its sinister mission on that fateful morning of 15 August 1971. When Bangabandhu’s body, riddled with bullets, lay lifeless at his home in Dhanmandi abettors to the conspiracy in the Pakistani army Headquarters, as Lifschultz states, were among the first to rejoice the news of this macabre happening.

The tragedy had turned full circle with the elimination of Bangabandhu, but the Bengali nation continues to atone for its collective guilt of giving birth to those who like cunning wolves stealthily moved from behind and felled a titan.

Author : Golam Sarwar Chowdghury is Professor of English at university of Liberal Arts Bangladesh (ULAB).