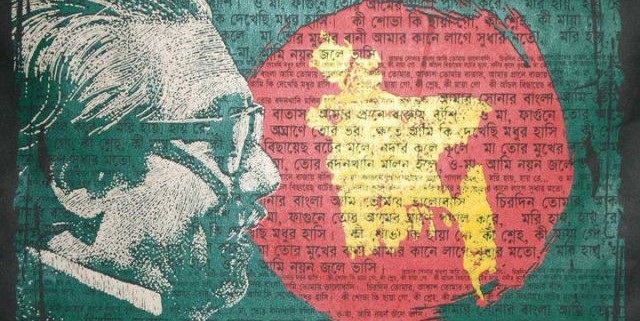

Bangabandhu and Bangladesh

By Muntasir Mamun

The inhabitants of Bangladesh had dreamt of a free land for long. Many individuals had sought to materialise this dream in the past. Many had spoken about that land during the first forty years of the last century. That plan was once again drawn during the partition of India. Moulana Bhashani had spoken about an independent territory for the Bangalis during the decade of 1960s. But none could give complete shape to that dream. That dream was finally realized on 16 December 1971 under the leadership of a pure Bangali – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It was he who could erect for the Bangalis the geographic boundaries of a free state. Bangabandhu, Father of the Nation, or Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – in whatever name we may call him – his iconic figure looms large whenever we talk about Bangladesh. That is why, his name has become ingrained in our history and because of that we repeatedly reminisce about him. There are numerous claimants to the Bangladesh dream. Many might have dreamt it; many had talked about Bangladesh through signs and gestures; but Sheikh Mujib had completed the task like an architect. Like many others, he also thought of Bangladesh, but preparations for the purpose continued up to 1971.

The inhabitants of Bangladesh had dreamt of a free land for long. Many individuals had sought to materialise this dream in the past. Many had spoken about that land during the first forty years of the last century. That plan was once again drawn during the partition of India. Moulana Bhashani had spoken about an independent territory for the Bangalis during the decade of 1960s. But none could give complete shape to that dream. That dream was finally realized on 16 December 1971 under the leadership of a pure Bangali – Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. It was he who could erect for the Bangalis the geographic boundaries of a free state. Bangabandhu, Father of the Nation, or Sheikh Mujibur Rahman – in whatever name we may call him – his iconic figure looms large whenever we talk about Bangladesh. That is why, his name has become ingrained in our history and because of that we repeatedly reminisce about him. There are numerous claimants to the Bangladesh dream. Many might have dreamt it; many had talked about Bangladesh through signs and gestures; but Sheikh Mujib had completed the task like an architect. Like many others, he also thought of Bangladesh, but preparations for the purpose continued up to 1971.

Moulana Bhashani had also spoken about Bangladesh in open forums. But his role was negligible in this field. However, all those dreams and speeches had prepared the people. Journalist Abdul Matin had written in his autobiography: “He met Mujib one day at noon during the military rule of Ayub Khan. Sheikh Saheb said that he did not care Ayub Khan. He knew the minds of the people. After remaining silent for a few moments, he talked about using the Agartala case in the anti-Ayub movement”. It can be said in this context that the Agartala conspiracy case might not have been fully cooked up. That dark gentleman had emerged from the very midst of our rural paddy culture. His heart was vast like nature itself, and he wanted to cover the Bangalis with that – the whole of Bangladesh. The Bangalis had repaid that gesture as long as he lived.

One day on 27 March 1971, a Major suddenly told the Bangalis to snatch freedom and they jumped for that – the Bangalis are not made of such stuff. It took a long time to awaken them and it was Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman who succeeded in doing that. Consequently, whether one likes it or not, can there be any option other than calling him the ‘architect of our freedom’? And it was not that Sheikh Mujib became ‘Bangabandhu’ overnight in 1970 and ‘Father of the Nation’ all of a sudden in 1972. It took him three decades to become Bangabandhu. If we consider the period between 1940 and 1974, we shall see that Sheikh Mujib became Bangabandhu and Father of the Nation for several reasons. These were: the vastness of his heart, his humanism and tolerance, his appearance, dresses and words; all of these had demonstrated his intention to maintain everlasting bonds with a huge population. Some information and proofs could be obtained about the long-drawn conspiracies of the villains of 1975 for seizing power. Khandakar Mostaque is an example. Evidence of the conspiratorial mentality of this principalvillain in our history could be observed even before the liberation war. The frontline leaders of Awami League had visited Bangabandhu at his Dhanmondi residence on 25 March 1971 and asked him to remain cautious. Only Khandakar Mostaque was not seen there. After independence, he lobbied with Dr. Wazed Miah to become Foreign Minister with seniority. Later, in 1974, Dr. Wazed Mia saw after going to Khandakar Mostaque’s residence that one Major Rashid was going out of the house after secret talks with him.

There has been much debate about the message of Sheikh Mujib broadcast by Mr. Hannan from Chittagong on 26 March 1971. Dr. Wazed Miah had written: “Bangabandhu’s message was in a taped form. After transmitting that message from Dhaka’s Baldah garden, that brave member of EPR had sought fresh orders by contacting Bangabandhu’s residence over telephone. Bangabandhu then directed the EPR member via Mr. Golam Morshed to leave that place instantly after throwing the transmitter into the pond of Baldah garden.” I shall not go into the debate on whether this information was correct or not. I understand as an ordinary student of history that the country called Bangladesh was founded at the very start of March 1971 and that had happened at the directive of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Professor Borhanuddin Khan Jahangir highlighted this in a very clear and logical manner in his essay titled ‘Accountability of the State’. He wrote: “The 35 directives issued by Sheikh Mujib had laid the ground for all-out noncooperation with the Pakistani state through resistance and rejection of its authority and complete cooperation of the Bangali masses with their administration through establishment of a pro-people authority.

—— The Bangali people had nurtured the thought of becoming the inhabitants of a separate, different and independent state in their bosom, head and heart even before the commencement of the war.” From the 1960s, Bangabandhu had two objectives. One of those was unambiguous, while another was unclear or something akin to a dream. The clear objective was to build up the Awami League, spread the organization throughout the country and establish a civil society by going to power on Awami League platform. There were infightings within the Awami League, which was natural for a big party. But Sheikh Mujib’s organizational capacity was unique. He had the two qualities of tolerance and flexibility, which were needed for making the party bigger. I have even seen old people in remote rural areas, whose only possession was a tea-stall, who never got anything from the party, but had never left it after coming to the fold of Awami League at the behest of Sheikh Mujib. There are many more selfsacrificing Awami Leaguers in the nooks and corners of Bangladesh, who did not leave the party despite becoming destitute. The leaders, however, do not keep track of them. Besides, Sheikh Mujib had such individuals as his

companions, without whose help he might not have achieved his cherished goal. As a result, the Awami League became bigger, expanded after the 6- point movement and simultaneously Sheikh Mujib became the undisputed leader of the masses. He also had tremendous self-confidence and courage. The blossoming of the party had also raised his confidence in himself as well as the people. That was why he could transform the 6-points into a 1-point. And this was his unclear vision or dream. That he was unwavering on the question of this

objective and had the necessary courage and confidence for materialising this dream were highlighted during the Agartala conspiracy trial. Fayez Ahmed had written about an incident during this trial. He was sitting beside the main accused Sheikh Mujib. They were not allowed to talk inside the court.

Sheikh Mujib tried to draw the attention of Fayez Ahmed a number of times in order to say something. Fayez Ahmed said, “Mujib Bhai, conversations are not allowed. I can’t turn my head. They will throw me out.” A loud reply came forthwith, “Fayez, one has to talk to Sheikh Mujib if he wants to stay in Bangladesh.” –

——-He did not know then that this symbolic utterance by Sheikh Mujib was not meant for any individual person; it was a message for the entire people of a country, which could ignite fire. Sheikh Mujib returned to the Bangladesh of his dream in 1972. Now his role was not that of a wager of movements. Rather, he played his part in materialising the dream of a Golden Bangla. He worked tirelessly with that objective in mind until 15 August 1975. Reconstruction of the country was in full swing and the Constitution was already framed by that time. The biggest achievement of Bangabandhu and the then Awami League government was to endow the country with a Constitution. I do not know whether there is any other example of a country where it was possible to provide a Constitution so swiftly in the aftermath of such a bloody war. The four core principles of the state were proclaimed through this Constitution, which could have been termed as radical in the context of the then realities. These were: Democracy, Socialism, Secularism and Nationalism. These principles in fact contained those very ideals for which the liberation war was fought. This was especially true of secularism. That is why the military generals had at the very outset struck at these core principles, especially secularism. Besides, the Constitution described the social, economic and political rights of citizens and the philosophy of the state. In other words, it indicated that the liberation war was waged for establishing a civil society in place of a military-dominated one. The 1972 Constitution had incorporated the necessary institutions for a civil society; it firmly strove to lay the foundation for a vibrant civil society in Bangladesh.

In this context, Bangabandhu had said in one of his speeches: “I do not know whether democracy was initiated immediately after a bloody revolution in any country of the world. —– Elections have been organised. The right of vote has been expanded in scope by lowering the voting age from 21 to 18. Bangladesh’s own aeroplanes are now flying in the skies of different countries; a fleet of commercial ships has also been launched. The BDR is now guarding the borders. The ground forces are ready to repel any attack on the motherland. Our own navy and air-force are now operational. The police force and thanas have been rebuilt, 70 percent of which were destroyed by the Pakistanis. A ‘National Rakkhi Bahini’ has been raised. You are now the owners of 60 percent of mills and factories. Taxes for up to 25 bighas of land have been exempted. We do not believe in the policy of vengeance and revenge. Therefore, general amnesty has been declared for those who were accused and convicted under the Collaborators’ Act for opposing the liberation war.” But the people were not inclined to appreciate the framing of Constitution, its principles, and the successes of Sheikh Mujib due to rising price of essentials and the law and order situation. Not only was Bangabandhu killed along with his family, the husband

of his sister Abdur Rab Serniabat and his nephew (sister’s son) Sheikh Moni

were also killed along with their family members. It was quite apparent that intense hatred had worked behind this; otherwise this kind of brutality could

not have been carried out in cold blood. The assumption that if any of the family members survived, then he would come forward to provide leadership was also at work. That this assumption was not unfounded has been proved subsequently.

Bangabandhu’s two daughters Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana survived as they were staying abroad. Later, Sheikh Hasina became the leader of the Awami League and is now once again waging a struggle to reinforce the civil society.

It is clear from the manner in which the Bangabandhu family was assassinated that there were local and international conspiracies and a long time was spent for planning it. The conspirators took risks and that risktaking paid off. A faction of the Awami League led by Khandakar Mostaque was involved in it. It can be cited as evidence that it was during Mostaque’s rule that the four Awami League and national leaders Tajuddin Ahmed, Syed Nazrul Islam, Mansur Ali and Kamruzzaman were killed inside the central jail on 3 November 1975. Saudi Arabia and China recognised Bangladesh immediately after Khandakar Mostaque came to power. Relationships with Pakistan and the USA also improved. Consequently, the theory that foreign powers had a hand in the killings cannot be dismissed outright.

Almost three decades after Sheikh Mujib’s killing, the people can once again feel what Sheikh Mujib really was and why he was awarded the title ‘Bangabandhu’. People can realize today that he wanted to raise the stature of the Bangalis, and one way of doing that was to give back the honour to the unarmed people. Whichever parties and persons might have ruled Bangladesh after his murder, his name could not be erased from the minds of the people. That effort still continues. That is because it is evident today that we got that honour only once, that path was opened for us only once in 1971, when Bangladesh succeeded in ousting all kinds of armed thugs under the leadership of an unarmed Bangali called Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Despite the many flaws and heaps of criticisms levelled against Sheikh Mujib, we should note, just as an opponent of Sheikh Mujib and Awami League – Moudud Ahmed – had written (translator’s translation from Bengali): “The appearance of Sheikh Mujib was the biggest event in the national history of Bangladesh. His burial did not take place through his death. More pragmatic, efficient, capable and dynamic political personalities than Sheikh Mujib might have emerged or may emerge, but it will be very difficult to find someone who has contributed more to the independence movement of Bangladesh and the shaping of its national identity.” He had endeavoured to uphold the interests of the Bangalis throughout his life and had never compromised until his objectives were attained. That is why the Bangalis gave him the title ‘Bangabandhu’ and ‘Father of the Nation’ out of sheer love and emotion. His lifestyle was like that of an ordinary Bangali of eternal Bengal; that is why he could so intensely connect with the ordinary people and their communities. He possessed all the attributes of an ordinary Bangali.

But his love for his people and country was extraordinary, almost blind. He used to say: “My strength is that, I love human beings. My weakness is that, I love them too much.” The position of Bangabandhu vis-à-vis other doers in the civil society of Bangladesh will become clear if the events of 1971 and 1971-75 are analysed. It is impossible to write the history of pre and post-independence

Bangladesh without mentioning him. The names of two great Bangalis will remain forever shining in the minds of the Bangalis. One is Rabindranath Thakur and the other is Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. One had shaped the Bengali language and wrote the national anthem of Bangladesh. The other materialised the age-old dream of the Bangalis by helping create an independent territory called Bangladesh for an entire nation. I feel proud for this, and my posterity will also be so. The names ‘Bangali’ and ‘Bangladesh’ will continue to live on. And that is why Anandashankar Ray had written: “As long as the Padma, Meghna, Gouri, Jamuna flows on, Your accomplishment will also live on, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman.”

Translation: Helal Uddin Ahmed

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!