Bangabandhu – A Name that Goes with Eternity

Embracing Bangabandhu at the Algiers Non-Aligned Summit in 1973, Cuba’s Fidel Castro remarked, “I have not seen the Himalayas. But I have seen Sheikh Mujib. In personality and in courage, this man is the Himalayas. I have thus had the experience of witnessing the Himalayas.”

This Sheikh Mujib is not just a mere individual or a name. He in an institution. A movement. A revolution. An upsurge. A tidal boar. A Lenin, a Mao, a Netaji, a Gandhi, a Fidel, a Kemal… He is the essence of epic, poetry and history. He is the architect of a nation – the Bengali Nation. He is Bangabandhu – friend of Bengalis.

The history of Bengali Nation goes back a thousand years. That is why contemporary history has recognised him as the greatest Bengali of the thousand years. The future will call him the idol of eternal time. And he will live, in luminosity of a bright star, in annals of historical legends. He will show the path to the Bengali Nation that his dreams are the basis of the existence of any nation struggling for freedom. A remembrance of him is the culture and the society that Bengalis have sketched for themselves. His possibilities, the promises put forth by him, are the fountain-spring of the civilised existence of the Bengalis.

Bangabandhu’s political life began as a humble worker while he was still a student. He was fortunate to come in early contact with such towering personalities as Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and AK Fazlul Huq, both charismatic Chief Ministers of undivided Bengal. Adolescent Bangabandhu grew up under the gathering gloom of stormy politics as the aging British Raj in India was falling apart and the Second World War was violently rocking the continents. He witnessed the ravages of the war and the stark realities of the great famine of 1943 in which about five million people lost their lives. The tragic plight of the people under colonial rule turned young Bangabandhu into a rebel.

This was also the time when he saw the legendary revolutionaries like Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose and Mahatma Gandhi challenging the British Raj. Also about this time he came to know the works of Bernard Shaw, Karl Marx, Rabindranath Tagore and rebel poet Kazi Nazrul Islam. Soon after the partition of India in 1947 it was felt that the creation of Pakistan with its two wings separated by a physical distance of about 1200 miles was a geographical monstrosity. The economic, political, cultural and linguistic characters of the two wings were also different. Keeping the two wings together under the forced bonds of a single state structure in the name of religious nationalism would merely result in a rigid political control and economic exploitation of the eastern wing by the all-powerful western wing which controlled the country’s capital and its economic and military might.

Bangabandhu started his fight against the British colonial overlords and then he directed his wrath against the then Pakistani neo-colonialists. Step by step he prepared his people for their eventual destination. He was in the forefront of mass movements. From his imprisonment in 1949 he gave active support to the formation of the first mass-based opposition political party, the Awami League, under the leadership of Maulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhasani, which subsequently spearheaded the struggle for independence. In the 1954 provincial elections, the Bengalis overwhelmingly voted the Awami League-led United Front to power. The victory was, however, short-lived. In order to maintain their sway and dominance, the rulers in the western wing of Pakistan through coercive means, imposed military rule in 1958. Bangabandhu and other nationalist leaders put up stiff resistance against it and were detained for years together.

In 1961 Bangabandhu was released from jail after he won a writ petition in the High Court. Then he started underground political activities against the martial law regime and dictator Ayub Khan. During this period he set up an underground organisation called “Swadhin Bangia Biplobi Parishad” or Independent Bangia Revolutionary Council, comprising outstanding student leaders in order to work for achieving independent Bangladesh.

Keeping the essence of Swadhin Bangladesh, Bangabandhu placed his historic Six-Points in 1966. He called for a federal state structure for Pakistan and full autonomy for Bangladesh with a parliamentary democratic system. The Six-Points became so popular in a short while that it was turned into the Charter of Freedom for the Bengalis or their Magna Carta. The Army Junta of Pakistan threatened to use the language of weapons against the Six-Points movement and the Bangabandhu was arrested under the Defence Rules on May 8, 1966. To subdue him, Bangabandhu was charged with secession and high treason, which was known as the infamous Agartala Conspiracy Case. But mass people burst into upsurge against his arrest.

With the defeat of Ayub Khan regime in 1969 in a mass-upsurge which led to the unconditional withdrawal Agartala conspiracy case, Bangabandhu had become an undisputed, home grown hero for the Bengali nation. People’s admiration to his unfathomable courage and yearning for his guidance convinced that he was the friend of Bengal. They then start calling him Bangabandhu. The torch of politics Bengali Nation was truly and irreversibly in his hands. He would carry it ahead, undaunted in his determination to transform the destiny of his people to make Shonar Bangla.

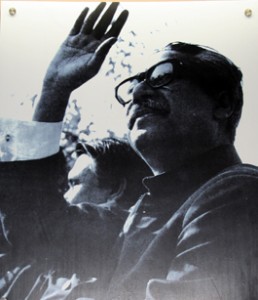

Bangabandhu’s finest hour came on 7th March 1971. His historic speech on that day changed the course of the history of struggle for independence in the then Pakistan and gave millions of Bengalis a new sense of direction. Bangabandhu possessed the rare quality of harnessing the awesome power of the masses that overthrew the military regime standing in the way of Bangladesh’s liberation.

He declared in his speech, “The struggle now is the struggle for our emancipation, the struggle now is the struggle for our independence.” In this historic speech, Bangabandhu urged the nation to break the shackles of subjugation and declared, “Since we have given blood, we will give more blood. The people of this country will be liberated Inshallah. He called upon people to turn every house into a fortress with whatever they had to fight the enemy.

He advised the people to prepare themselves for a guerrilla war against the enemy. He asked the people to start a total non-cooperation movement against the government of Yahya Khan. There were ineffectual orders from Yahya Khan on the one hand, while the nation, on the other hand, received directives from Bangabandhu’s Road 32 residence. The entire nation carried out Bangabandhu’s instructions. All institutions, including government offices, banks, insurance companies, schools, colleges, mills and factories obeyed Bangabandhu’s directives. The response of the Bengalis to Bangabandhu’s call was unparallel in history. It was Bangabandhu who conducted the administration of an independent Bangladesh from March 7 to March 25.

Another finest hour for Bangabandhu was when he declared independence of Bangladesh and all-out guerrilla war began against the Pakistani oppressive regime. In his declaration he said, “This may be my last message. From today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh, wherever you are and with whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh and final victory is achieved.”

And the victory achieved on the 16th December 1971 – a dream come true for Bangabandhu. Thousands of people sacrificed their lives in the name of Bangabandhu. It was his political inspiration and moral persuasion that made mass people to embrace martyrdom in Bangabandhu’s name. The quest for his independence became synonymous with his title “Bangabandhu”. And eventually he embraced martyrdom on the 15th August 1975 for the Bengali Nation.

The multifaceted life any great man cannot be put together in language or colour. Bangabandhu was such a great man that he has become greater than his creation. It is not possible to hold him within the confines of picture-frame when his greatness is so unfathomable. He is our emancipation – for today and tomorrow. The greatest treasure of the Bengali nation is preservation of his heritage and sustenance of his legacy. He has conquered death. His memory is our passage to the days that are to be.

By: shazzad

[Shazzad Khan works for Manusher Jonno Foundation]