THE STORY OF AN INSPIRATIONAL FIGURE

The genre of biography has been undergoing lots of changes in terms of themes and styles ever since the publication of Boswell’s Life of Dr. Johnson (1791). While Boswell’s work is regarded as the finest literary biography ever written, and still enjoys its status as ‘a classic of language’, many other biographies assume the role of history. As Thomas Carlyle put it in his Heroes and Hero Worship (1840) “the history of the world is but the biography of great men”. Ralph Waldo Emerson was more advanced than Carlyle in this regard. He aimed at closing the gap between biography and history in his Essays: First Series (1841). To quote: “There is properly no history; only biography”. The tendency to overlap between biography and history has come down to us.

The genre of biography has been undergoing lots of changes in terms of themes and styles ever since the publication of Boswell’s Life of Dr. Johnson (1791). While Boswell’s work is regarded as the finest literary biography ever written, and still enjoys its status as ‘a classic of language’, many other biographies assume the role of history. As Thomas Carlyle put it in his Heroes and Hero Worship (1840) “the history of the world is but the biography of great men”. Ralph Waldo Emerson was more advanced than Carlyle in this regard. He aimed at closing the gap between biography and history in his Essays: First Series (1841). To quote: “There is properly no history; only biography”. The tendency to overlap between biography and history has come down to us.

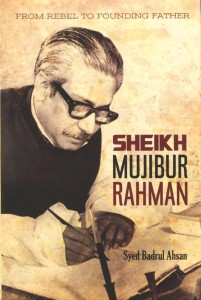

Syed Badrul Ahsan’s biography of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, too, is not an exception. It deliberately distances itself from Boswell’s treatment of the genre, and leans more towards Carlyle’s and Emerson’s notion about biography, allowing a considerable overlap between the two subjects. This is for obvious reasons. The subject of Boswell’s biography was Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), popularly known as Dr. Johnson, who was an English poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer, and ‘arguably the most distinguished man of letters in English history’, while the subject of Ahsan’s biography is a Bangladeshi pre-eminent politician and statesman, arguably the best Bengali ever, and honoured in Bangladesh as the father of the nation. Both subjects are larger than life characters — the former being presented artistically with utmost creativity, originality and literary skill and the latter historically by a gripping but candid narrative.

While there is a growing trend of muckraking biographies all around the subcontinent, Ahsan focuses on the significant things needed to be brought to light to deal with the subject of his study. Even Mahatma Gandhi’s biographers —Joseph Lelyveld or Jad Adams or Nehru’s biographer Stanley Wolpert orIndira Gandhi’s biographers — Pupul Jayakar, Zareer Masani, Inder Malhotra and Katherine Frank tried, on the pretext of writing biography, to wash their subjects’ dirty linen in public. The subjects of their biographies may have had feet of clay, but that hardly overshadows their achievements and hence should not be treated with a view to tickling popular fancy.

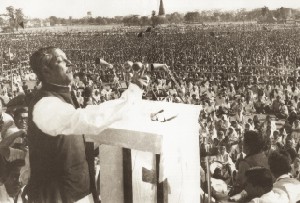

Ahsan’s biography of Sheikh Mujib is not at all of the cheap muckraking kind. He has rather come up with a sublime treatment of his subject and left no nasty taste in the mouth. He has chosen as his subject a man who stands no comparison with any other political personalities of his country. Mujib bears comparison with Abraham Lincoln of America, Vladimir Ilyich Lenin of Russia, Winston Churchill of England, De Gaulle of France, Mao-Tse-Tung of China, Ho Chi Minh of Vietnam, Sukarno of Indonesia, Kamal Ataturk of Turkey, Mandela of South Africa, Patrice Lumumba of Congo, Jomo Keneyatta of Kenya, Ben Bella of Algeria, Fidel Castro of Cuba, Mahatma Gandhi of India and Jinnah of Pakistan. Mujib’s life is deeply embedded in the history of the birth of Bangladesh. He was the fearless fighter of the Language Movement of 1952; the pioneer of the democratic movement of 1962; the originator of the Six-Point Movement of 1966; the life-force of the Mass Movement of 1969; the enviable victor of the election of 1970 and, above all, the greatest hero of the Liberation War of 1971. He is undisputedly the architect of independent Bangladesh. The story of such an iconic personality needs to be told and retold dispassionately by the right persons for the younger and future generations at home and abroad. The writer of the foreword of this biography, National Professor A. F. Salahuddin Ahmed, too, feels like that and is convinced that Syed Badrul Ahsan’s work on Sheikh Mujib “will do that job to the satisfaction of all.”

With this end in view, the biographer seems to have done that job to the best of his ability. He has been a writer and journalist for about three decades now and written considerably on Bangladesh politics, South Asian history, American presidential history, Soviet and Chinese communism and politics in post-colonial Africa. To write about the tumultuous events of the Bangladesh Liberation War (1971) and of the life of Sheikh Mujib was always a deeper passion with him which he, perhaps, inherited from his father. In his own words: “My association with Sheikh Mujibur Rahman… began in early 1968 when I heard my father speaking in whispers with his colleagues about the charge of conspiracy laid at Mujib’s door by the Pakistan government. My father’s conviction was absolute: Mujib, a believer in constitutional politics, was made of better stuff.” But he never killed his passionate subject of writing with kindness or emotion. His intellectual rigour, emanating from his research as a Fellow at the Jawaharlal Nehru Institute of Advanced Studies on three major Bengali political figures–Chittaranjan Das, Subhas Chandra Bose and Sheikh MujiburRahman — has found expression in this biographical account.

Ahsan tries quite arguably to establish Mujib as the most inspirational figure in Bangladesh politics by portraying the transformation of his role spread over a period of about three decades, starting from the Bengalis’ struggle for self-dignity and ending in the War of Independence, and even after he was killed. As Ahsan puts it in the preface of his book: “…in the broad perspective of history, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman remains a metaphor for Bangladesh and for its long sustained struggle for freedom. In life he was the Bengalis’ spokesman in the councils of the world. In death, he continues to be a powerful voice, forever ready and willing to speak for those who yearn for freedom and national self-dignity.” Ahsan tells us the story of the “rebel who did not give up and because he did not, Bangladesh was born.” What Stanley Wolpert said about Mohammad Ali Jinnah is more applicable to Mujib. To quote: “Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state. Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.” Ahsan must have meant to say that Mujib, too, did all three and he did them in a far better and more successful way than Jinnah. A perfect foil for Jinnah, he altered the course of history by aborting Jinnah’s so-called ‘two-nation theory’, modified the map of the world by demarcating 56,000 square miles for a new-born country and created a nation-state called Bangladesh. And how a young follower of the All India Muslim League had gradually been transformed into a veteran political leader, who led his country and people from the front to the way to independence through a revolution and finally was consumed by a counter-revolution, constitutes the factual plot around which Ahsan’s biography revolves.

Ahsan’s book showcases all the historic events associated with the political birth of Bangladesh under Mujib’s able and charismatic leadership. He has substantiated his proposition with facts and figures which speak for themselves. The book is organized into seven parts, beginning with Mujib’s initiation into politics in the late 1930s and ending in his murder, and tags a postscript on to its end which is germane to the core parts. The core parts discuss at necessary length subjects/issues/events/matters like Mujib’s initiation into politics, Awami Muslim League, Pakistan after Jinnah, Language Movement, Mujib as an emerging star, politics in crisis, at the epicenter, martial law and Tagore, taking charge after Suhrawardy,1965 war and East Pakistan, Six-Point programme, rise of Bhutto, Agartala and resurgent Bengal, Bengal’s spokesman, Pakistan’s prime minister in waiting, Road to Bangladesh, Genocide and Mujibnagar, Trial in Mianwali, Triumph in Dhaka, Flight to freedom, Mujib in power, Shaping foreign policy, Emerging cracks, Mujib in Lahore once more, Gaining UN, losing Tajuddin, From pluralism to second revolution and Murder of Caesar.

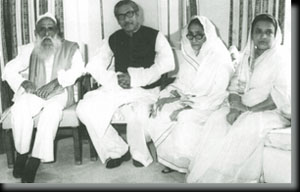

That Syed Ahsan writes good English is well known to his readers. His biography has been written in a lucid style. The liberal interpretation of facts and niceties of argument have endowed the book with the qualities of a successful biography. The pictures used in the book have added to its merit. It’s sure been worth a read. The good writer has more claim to the book’s success than anybody. From Rebel to Founding Father—Sheikh Mujibur Rahman—is a prized inclusion in the list of Mujib biographies in English.

**************************************

Rashid Askari dissects a biography of Bangladesh’s founder

From Rebel to Founding Father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Syed Badrul Ahsan Niyogi Books, New Delhi

Dr. Rashid Askari writes fiction and columns, and teaches English literature at Kushtia Islamic University, Bangladesh. Email: rashidaskari65@yahoo.com