#bangabandhu : Eminent scientist Professor Abdus Salam had been invited by the then Islamic Academy, Dhaka to give a lecture on religion and nationalism a couple of months before the presidential election in 1964. The Academy was housed in an old two-storey abandoned building. That house was demolished to construct Bailul Mokarram shopping complex in the late sixties. My friend Ahmed Safa, the late writer, and I attended the lecture.

After the seminar was over, the Director of the Islamic Academy, Abul Hashim, a politician and thinker, was chatting with Dr. Salam and some other distinguished persons including Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah and Dr. Qudrat-e-Khuda. All on a sudden, Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Dr. Mofazzar Ahmed Chowdhury, a reader in the political science department at the University of Dhaka, showed up on the veranda of the Islamic Academy. Seeing Prof. Salam and Abul Hashim in the auditorium, they joined them. It was a Sunday morning. Perhaps they had gone to Awami League office, opposite the Academy, for party work. We were listening to their conversation from a considerable distance.

Almost all major political parties in East Pakistan had been supporting “provincial autonomy.” Their idea of autonomy was some kind of “political autonomy.” But Maulana Bhasani and Sheikh Mujib’s concept of autonomy was different from that of other Bengali leaders. They demanded full provincial autonomy and an “autonomous economy” for East Bengal.

I still remember the gist of this informal conversation. Speaking on the provincial autonomy, Sheikh shaheb pointed out the disparity between the two wings of Pakistan. He quoted from Dr. Mahbubul Huq’s newly published Strategy of Economic Planning in Pakistan, and said that in order to redress the economic disparity between the two wings it was necessary to dismantle the central Planning Commission to create two powerful regional planning bodies. He emphatically said that the region should have the authority to tax, and the power to make fiscal and monetary policy on its own. So far as I can recollect, Dr. Salam endorsed the views of Sheikh Mujib. Bangabandhu further said that the provinces should have the power to form foreign policy and conduct foreign relations. It was two years before the announcement of his Six Points.

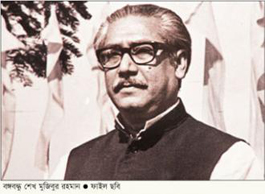

By the early 1960s, Sheikh Mujib was known to all as the standard-bearer of Bengali nationalism. It was the period of military dictatorship of Field Martial Ayub Khan. Sheikh Mujib was his greatest opponent. He fought relentlessly for the revival of democracy in Pakistan and provincial autonomy for East Pakistan. From the nationalist and from the conservative standpoint, his role in power politics was unparalleled.

In 1963, Sheikh Mujib went to London to consult with his ailing political guru, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, who was in self-exile. The two had detailed discussions on the political situation prevailing in Pakistan. Mujib didn’t like foreign involvement in achieving the rights of the people of East Pakistan.

Suhrawardy wrote in his unfinished memoirs: “Mujib has doubts that national unity and national integration will solve the problems of East Pakistan. He is not interested in the field of foreign politics as he does not believe that any foreign country should become deeply committed here; East Pakistan must work out its own destiny. Hence, there is no point seeking foreign political involvement.” [Memoirs of Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, P. 71]

After the death of Suhrawardy in December 1963, it became difficult to keep the party together. Ataur Rahman Khan was a gentleman politician. He had neither courage nor charisma. Neither he nor any other leader had any command over the younger leaders and workers. At that crucial time, Mujib took over the helm of the party. Sheikh Mujib not only led the Awami League, but also led the nation to independence in seven years.

After liberation, Bangabandhu had to tackle multifarious problems. He faced severe opposition from various quarters at home and abroad. Anti-liberation parties like Jamat-e-Islami, Muslim League and Nezam-e-Islam, which were banned by the government, and other reactionary forces, communal elements, and underground ultra-Left outfits went on with their conspiracy and anti-government propaganda. The political and social elite did not cooperate with the government. Because of economic hardship the ordinary people were frustrated. In the meantime, creation of Baksal — one-party rule — angered the Western capitalist bloc.

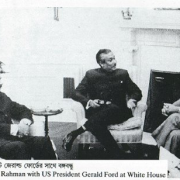

The Bangladesh liberation war got active support from the Soviet Union and its East European allies. Both the US and the Soviet Union were trying to gain influence in the impoverished nation. The influence of US was more than that of the USSR as the US was able to pour in more aid and assistance and its intelligence was more efficient and pro-active. Pakistani intelligence was also active and got support from the US. China and Muslim countries were against the Bangladesh freedom movement because of India’s total support to Bangladesh. In these circumstances, Bangabandhu had become a victim.

The people of Bangladesh had experienced the military coups of Ayub and Yahya Khan. Both were bloodless. But the August 15 coup was the worst possible military savagery.

Who killed Sheikh Mujib? Dalim-Faruk and others in the army were mercenaries. And Mushtaq? Brutus was better.

Samar Sen, an astute diplomat, was India’s high commissioner to Bangladesh in 1975. He saw the political developments in Bangladesh from close quarters. Twenty-three years after the coup, Sen told the Frontline journalist Sukumar Muralidharan in 1998: “We had been keeping in touch with all elements within Bangladesh. India’s intelligence services — whose operations few of us know much about — retained contact even with elements hostile to Sheikh Mujib. He felt that these contacts were uncalled for and asked us to stop them. We did so. As a result, until the time of the coup, we had no idea that things had deteriorated quite so badly. In retrospect, it is clear that the August coup, apart from being a rude awakening, was perhaps a logical outcome of the situation of chaos that prevailed.”

The August 15 military action was a coup with a difference. It changed, among other things, the secular and democratic character of Bangladesh.

I saw Bangabandhu for the first time in 1954 on the banks of the mighty Padma at Aricha ghat. The last I saw him was in the Bangabhaban Darbar Hall on July 31, 1975. To him, personal relationship was very important. He maintained excellent relations with his opponents and adversaries. Two weeks before the 1973 elections, National Awami Party chairman Maulana Bhasani was admitted to PG Hospital. Bangabandhu rushed to visit him. Hearing the voice of Bangabandhu, the Maulana sat up from the bed. Bhasani touched the hands of Mujib and wished him all success in the election. He stressed on “a stable government” under his premiership.

While in the IPGMR, the Maulana did not have the chance to eat any food supplied by the hospital. Admirers sent home-made food for him. Begum Fazilatunnesa Mujib herself went or sent somebody to the hospital almost everyday with big tiffin-carriers. She cooked small fish curries with hot green chilly and spices to the taste of the Maulana. This gesture of the Mujibs annoyed the leaders and candidates of NAP.

I would like to cite another anecdote. A couple of months before the August tragedy, poet Jasimuddin asked me: “Bhai, could you accompany me to Dhanmondi? I’ve an urgent talk with Bangabandhu.” I gladly agreed. So far as I can recollect, the rickshawalla demanded taka two. It was exorbitant. The poet got angry. He haggled with the rickshaw-puller over the fair and hired the rickshaw from Bangladesh Bank to Bangabandhu Bhavan for taka one and a-half.

On reaching Bangabandhu Bhavan, the poet paid and patted the rickshawalla and walked straight to the drawing room. I followed him. Bangabandhu came down from the first floor. The two great Bengalis exchanged warm greetings and sat down on a sofa.

The poet said: “You’re from Faridpur, I’m also from Faridpur (district). I’ve come to you for a tadbir (a favour). My son-in-law is your son-in-law. Isn’t it?” “Of course,” Bangabandhu laughed and quipped: “Your son-in-law (meyejamai) is my son-in-law. I do understand what you want to say. You and Bhabi should not worry for Maudud. He is alright in jail. He will be released as soon as possible. I’m giving the order.”

Then they chatted for some time. The poet was highly gratified by the gesture of the president and supreme leader of the nation. Bangabandhu knew very well that the palli-kavi shouldn’t be entertained with tea or coffee. So, he asked his servant to serve him with muri, gur (molasses) and coconut — favourites of the poet.

This was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. As a politician and statesman, he was not above mistakes or follies. As a mortal human being, he had his weaknesses and limitations. History will absolve all his mistakes and weaknesses. As the independence hero and nationalist leader, he is second to none.

Author : Syed Abul Maksud is a noted writer, researcher and columnist.

“Why did they kill Bangabandhu? I’m feeling very bad [about it],” a six-year old Suha asked his father while visiting the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum in the city on Monday.

“Why did they kill Bangabandhu? I’m feeling very bad [about it],” a six-year old Suha asked his father while visiting the Bangabandhu Memorial Museum in the city on Monday.