A statement before the Supreme Court of Bangladesh By Lawrence Lifschultz

Ref: Writ Petition 7236 of 2010

Regarding the Trial & Execution of Abu Taher in July 1976

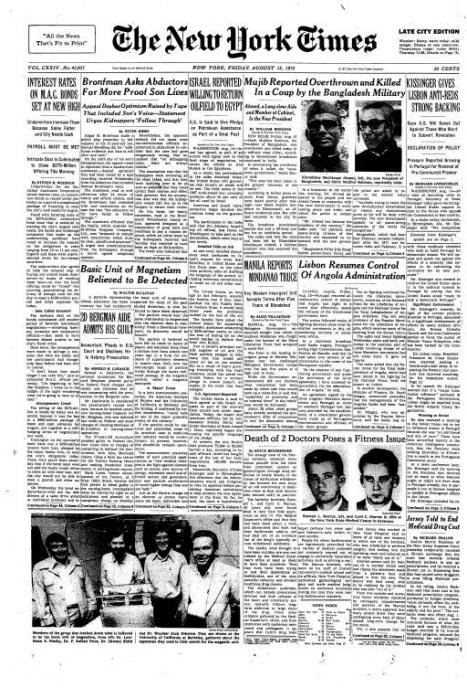

My name is Lawrence Lifschultz. I am a writer by profession. In July 1976 I was South Asia Correspondent of the Far Eastern Economic Review (Hong Kong) and a contributor to the BBC and The Guardian (London). In January this Court requested that I appear before it in order to give evidence on what knowledge I may possess pertaining to the case of Colonel Abu Taher.

On 3 February 2011, M. K. Rahman, the Additional Attorney General of Bangladesh, read out my Affidavit to this Court. I was unable to travel to Bangladesh in January because a family member had recently been in a serious accident and I was simply unable to leave.

Today it is one of the great honours of my life to be present before you in this Court. As the Court drew its deliberations to a close, you again graciously made a second request that I travel to Dhaka and appear before you. By then circumstances had changed and I was able to make the journey.

We are all here because of one of the most essential elements of civilised society. It is called “memory”. We have come to remember what happened in this city nearly thirty-five years ago. Some of us remember it well. Others were just children then. But, we are here because many of us refused to forget. It became our duty to remember.

For thirty-five years it has been my hope that one day I would stand in a courtroom aware that a verdict would soon be rendered in Taher’s case, and that the verdict would declare, whether or not, Abu Taher’s trial and execution in 1976 had been illegal, but also a fundamental violation of both his constitutional and human rights.

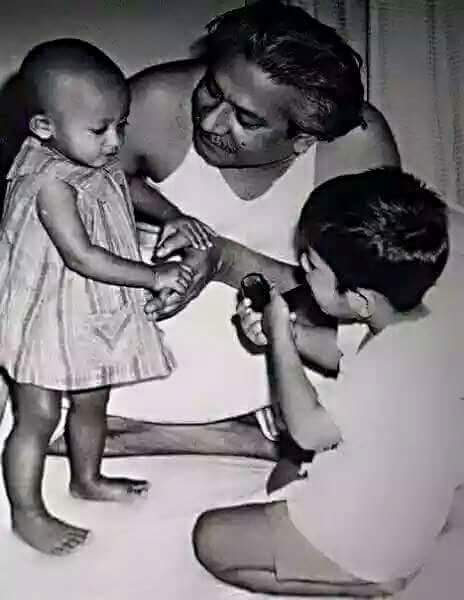

I did not know until a few months ago that it would be your Courtroom, nor did I know your names would be Justice Shamsuddin and Justice Hussain. We do not pre-judge your verdict. But, like others, I have hoped for a day like this one, these many decades. Only last week, Taher’s daughter Joya told me, “I have been waiting my whole life for this particular moment.” She was five years old when her father died. So you see, after a lifetime of waiting, many have come before you in search of justice for Abu Taher.

A year after Abu Taher was executed a meeting was organised at Conway Hall in London by a group of relatives and some of Taher’s former colleagues. Only a year after he had died people gathered to remember him. As you know, such a meeting in Dhaka would have been impossible in 1977. Many who might have attended were in prison. I was asked to speak at the Conway Hall meeting. As a journalist, I was not certain I should accept the invitation. Would my independence and objectivity be questioned? At the time I explained to those in attendance why in the end I accepted the invitation to speak. Certain of the remarks I made then I believe still have meaning today.

As I stood at a podium in Conway Hall, I said: “As a writer and journalist, I make a distinction, which some may find hard to see, between objectivity and neutrality. There can be no compromise or qualification on objectivity, as there can be no compromise with the pursuit of accuracy, but I also recognise there is no ‘neutrality’ on certain questions. That is why I have accepted the Taher Memorial Committee’s invitation to speak. When it comes to a question of secret trials and secret executions, I am not neutral. I condemn them whether they have been carried under the orders of Franco, Stalin or General Ziaur Rahman.” “A year ago, by a coincidence of timing, I happened to arrive in Bangladesh as just such as case was about to begin, full of its own dimensions of death, betrayal and tragic injustice……….. I am an American by nationality, and in America we too have had in our history famous incidents of exceptional judicial debasement, where the institutions of law have been used to commit crimes “for reasons of state.” In America the names and memory of the executions of the Rosenberg’s, Joe Hill and Sacco & Vanzetti stand out most starkly.”

Today I am reminded most clearly of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, two poor Italian immigrants who came to America for a better life and instead found a frame-up. They were killed because we in America also have our Salauddin Ahmeds and our A. M. S. Safdars. In the time of Sacco and Vanzetti they were called Attorney General Palmer and J. Edgar Hoover.”

Today I mention Sacco and Vanzetti because last month [June 1977] — 50 years after their execution — Governor Michael Dukakis of the State of Massachusetts declared that in the official view of the state, Sacco and Vanzetti were innocent men and were wrongly executed. Governor Dukakis declared that each year, on the anniversary of their execution, the people of the State of Massachusetts where these two men were executed would observe “Sacco and Vanzetti Memorial Day.” I doubt whether it will take the people of Bangladesh so long to set right what happened on the gallows of Dhaka Central Jail a year ago.”

Who could have known it would have taken this long? Fifty years have not passed as in the Sacco and Vanzetti case. However, nearly thirty-five years have elapsed since Taher’s death. The time has come to face the issues squarely. Can we even call what Taher and his colleagues faced a “trail”? There existed a “Special Military Tribunal No. 1” which convened in Dhaka Central Jail. I was there. I stood outside the prison. I watched men, like Colonel Yusuf Haider, the so-called Tribunal’s chairman, walk through the prison gates.

Although they tried to hide themselves and cover their faces, I took their photographs. Soon they took my camera, my film and arrested me, under what charge I was never told. But, today no records can be found of this “ghost” Tribunal. Even, back then, they were trying to cover their tracks and keep hidden what they had done. Perhaps, only George Orwell, could explain to us where the records and transcripts have gone.

These men who committed this crime against Taher, were not like us, who gather here today. They did not want anyone in the future to come together to remember what they had done and who they were. They preferred that their crime stay hidden. As this Court has discovered, there are no documents. There are no transcripts. There are no “official records”. At the outset they sought to cover up what they were doing.

What these “men of power” did not reckon on was the persistence and determination of a handful of people that this history would not be lost but would be remembered. We are here to remember, and the Supreme Court of Bangladesh has now become an integral part of a ‘process of remembrance.’

This Court has arduously reconstructed a picture of what took place by requesting witnesses to voluntarily appear and also ordering reluctant witnesses to give testimony. The Court has also ordered a search for any and all surviving documents. You are to be commended for your diligence and seriousness of purpose.

As I indicated in my Affidavit, I do not believe what happened can even be formally called a “trial”. It was not even a “show trial” because the military government did not want to “show it.” General Zia’s regime feared the repercussions of an open court of law and the public reaction that would have ensued had a trial been held by a lawfully constituted court with a free press being able to report. In my January 31st Affidavit I have described in some detail how I met General Mhd Manzur, Chief of General Staff, at his office in the Cantonment a month before the Special Tribunal. I had known Manzur for several years. I also explained how Manzur had opposed Taher’s so-called trial, and according to what he told me in June 1976, he was doing everything he could to see that it would not take place.

Clearly, Manzur was outnumbered and outflanked. It would only be a matter of time before they would come for him. However, as I discussed in the Affidavit, Manzur sent an emissary to see me in England after Taher had been executed. He wanted me to know that he knew positively that General Zia had personally taken the decision to execute Taher well before Colonel Yusuf Haider and his team “opened for business,” albeit sordid business, behind the walls of Dhaka Central Jail.

At the end of January, Moudud Ahmed, who I once knew as a young human rights lawyer, made certain claims in the press, citing my work repeatedly but in almost every instance inaccurately. Mr. Ahmed has traveled far from the principles I once associated him with when he was young. This is not an uncommon phenomenon on the road to power. But, he did make one claim, which if true, has importance for this Court’s deliberations. Moudud Ahmed claimed that Ziaur Rahman had convened a gathering of 46 “repatriated” officers to discuss the sentence that should be passed on Taher. It is well known that not a single officer who had participated in the Liberation War was willing to serve on special Military Tribunal No. 1. But, General Zia’s special convocation of repatriates appears to have ended with a unanimous decision. They wanted Taher to hang.

Moudud claims his source for this story was General Zia himself. In this respect, Moudud’s version of events tallies with what General Manzur claimed to me regarding General Zia having personally taken the decision on what the verdict would be. One man Ziaur Rahman decided, on his own, to take another’s life. He then asked a group of about fifty military officers to endorse his decision.

What can we say about this? By what stretch of the imagination can we call this a “lawful procedure”? By what authority or law did this klatch of military men render unto themselves the role of judge and jury? Military dictatorships write their own rules and that is precisely what happened in this instance. In my view, perhaps the most accurate way to describe the events that took place behind the gates of Dhaka central jail in July 1976, would be to recognise that what really occurred was simply a form of “lynching” organised by the Chief Martial Law Administrator, General Ziaur Rahman. There was no trial. A facade was created and dressed up to look like a trial. Yet, even the facade quickly crumbled. If it was a trial, why was it not taking place in a Court? It took place in a prison. What sort of trial occurs in a prison? The answer is a trial that is not a trial.

Joya Taher has characterised what happened to her father as an “assassination”. The Special Military Tribunal No. 1 was the mechanism by which the assassination was accomplished. Perhaps, Joya Taher’s view is closest to the mark. Syed Badrul Ahsan has called the Taher case “murder pure and simple”. In an article published in July 2006, Ahsan writes, “When he [Lifschultz] speaks of Colonel Abu Taher and the macabre manner of his murder (it was murder pure and simple), in July 1976, he revives within our souls all the pains we have either carefully pushed under the rug all these years or have not been allowed to feel through the long march of untruth in this country.” (Syed Badrul Ahsan, “Colonel Taher, Lifschultz & Our Collective Guilt”, The Daily Star, 26 July 2006.)

Ahsan was only partly right. When he called the Taher case “murder pure and simple”, he left out the element of premeditation or perhaps he assumed it. Moudud Ahmed, whatever else he has done, has made clear that General Zia went about his murderous work in a premeditated fashion, and pre-meditation under the law, has great significance.

It means you understood what you were doing and you planned your crime accordingly. In criminal law premeditated murder is murder in the first degree. (Why Moudud Ahmed was an associate of this man and a minister in his government is a question for another day.)

In his 2006 article Ahsan also referred to the “long march of untruth” in Bangladesh. He was certainly correct about the ‘state of affairs’ five years ago. However, a new phase appears to have opened. The Supreme Court has declared the 5th and 7th amendments to be at variance with the constitution thereby invalidating the attempt of two successive martial law regimes to retrospectively immunise their past actions from any form of accountability. This Court in my opinion is boldly taking on issues that are at the very heart of a new and challenging period. This Court is an integral part of the culture of this society and it is potentially an instrument of change. In the United States the warren court broken down the doors of racial segregation and became a critical force in changing American society. Bangladesh in 1971 sought to break from the disastrous traditions of Pakistan’s history of martial law regimes and dictatorship. If the inviolability of the constitution and the “rule of law” are to mean anything, the civilian courts must become paramount, indeed hegemonic.

It must become impossible for a small group of military officers to ever again establish themselves as “judge and jury” and thus supersede the civilian judicial authorities. This is the heart of the matter. The question is not only whether “the rule of law” will be paramount, but also whether the judiciary can acquire the strength to secure its paramount position? The Supreme Court clearly shows it is intent on doing so. Of course, there are no guarantees.

The “mindset”, so characteristic of the Pakistan Army and other military dictatorships, must be broken if democracy and democratic freedoms are not once again to be endangered in this country. The courts can play a critical role in strengthening the institutions of democratic rule. By overturning the 5th and 7th amendments a significant step has been taken in making unambiguously clear to the armed forces that if they ever cross the line again and embrace armed dictatorship, they will face grave consequences for breaching the constitution and the “rule of law”.

The challenge before the Supreme Court in the Taher case is to determine whether the procedures that were followed by “Special Military Tribunal No. 1” can be considered in any way to have been legal or constitutional. If they were not, they should be appropriately characterised.

For Taher’s family this is the essential matter. Will the “verdict” of a Tribunal that had no legal standing under the constitution and whose own records have “disappeared”, be allowed to stand, or will the secret proceedings of July 1976 at Dhaka Central Jail be overturned and declared to have been unconstitutional and illegal? To Taher’s wife and three children this is what matters. Everything else is detail.

“Now I am eagerly waiting for the verdict,” Taher’s daughter, Joya, wrote me ten day ago. The verdict “will not bring back my dad,” she said, but it will bring an end the “kind of assassination” which took her father from her and her two brothers at such an early age. To have their father exonerated, and admired for the remarkable man he was, will bring some peace to their hearts. If you accomplish this Justice Shamsuddin and Justice Hossain, you will have accomplished a very great and good deed.

It was almost exactly thirty-five years ago this month that I finished writing “Abu Taher’s last testament”. It was the spring of 1977. I was young then. I was only twenty-six. Less than a year had passed since Taher’s trial any my deportation from Bangladesh. I was living in Cambridge, England at that time. I remember when I typed the last page. I reread the text and put a copy in an envelope.

I was living in a small house on Clare Street. I remember walking around the corner to a tiny post office where I knew the staff. I bought the requisite number of stamps and two Air Mail stickers. The envelope was addressed to Krishna Raj, Editor of the Economic & Political weekly in Bombay. I wondered if he would publish it. I slipped the envelope into the mailbox.

It was published as a special issue of EPW in August 1977 and would soon become part of a book on Bangladesh. The book would be banned in Bangladesh for over a decade. Of course, my first desire would have been to publish the manuscript in Bangladesh. Yet, for obvious reasons that was not possible.

Two crucial events compelled me to write “Taher’s last testament”. I had been trying to decide how to write an account of all that had taken place. Then two things happened. A copy of Taher’s secret testimony before the special military tribunal arrived on my doorstep. Someone had called me from London saying they were mailing me an important document that had been brought from Dhaka. When I received it, I read it and was transfixed. It was an eloquent statement by a man of remarkable courage and integrity.

What happened next settled the matter. I received a translation of letter that Lutfa, Taher’s wife, had written to her brother at Oxford. It was one of the most beautiful letters I’ve ever read. I would like to conclude my testimony to this Court by reading an excerpt from Lutfa’s letter. She is here today.

“My dear bora bhaijan,

I cannot think of what to write you today. I cannot realise that Taher is no longer with me. I cannot imagine how I will live after the partner of my life has left. It seems the children are in great trouble. Such tiny children do not understand anything. Nitu says, Father, why did you die? You would have been alive, if you were still here.’

The children do not understand what they have lost. Every day they go to the grave with flowers. They place the flowers and pray, ‘let me become like father.’ Jishu says that father is sleeping on the moon…

I am very fortunate…When he was alive, he gave me the greatest honour amongst Bengali women. In his death he gave me the respect of the world. All my desires he has fulfilled in such a short time. When the dear friends and comrades of Taher convey their condolences to me, then I think: Taher is still alive amongst them, and will live in them. They are like my own folk. I am proud. He has defeated death. Death could not triumph over him…

Although it is total darkness all around me and I cannot find my moorings, and am lost, yet I know this distress is not permanent, there will be an end. When I see that the ideals of Taher have become the ideals of all, then I will find peace. It is my sorrow that when that day comes, Taher will not be there.

Affectionately,

Lutfa