Bangabandhu – The Legend

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (March 17, 1920 – August 15, 1975) was a Bengali politician and the founding leader of Bangladesh, considered the father of the nation. He headed the Awami League, served as the first President of Bangladesh and later became its Prime Minister. He is popularly referred to as Sheikh Mujib , and with the honorary title of Bangabandhu (????????? Bôngobondhu , “Friend of Bengal”). His eldest daughter Sheikh Hasina Wajed is the present leader of the Awami League and a former prime minister of Bangladesh.

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman (March 17, 1920 – August 15, 1975) was a Bengali politician and the founding leader of Bangladesh, considered the father of the nation. He headed the Awami League, served as the first President of Bangladesh and later became its Prime Minister. He is popularly referred to as Sheikh Mujib , and with the honorary title of Bangabandhu (????????? Bôngobondhu , “Friend of Bengal”). His eldest daughter Sheikh Hasina Wajed is the present leader of the Awami League and a former prime minister of Bangladesh.

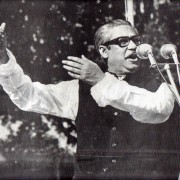

A student political leader, Mujib rose in East Pakistani politics and within the ranks of the Awami League as a charismatic and forceful orator. An advocate of socialism, Mujib became popular for his leadership against the ethnic and institutional discrimination of Bengalis. He demanded increased provincial autonomy, and became a fierce opponent of the military rule of Ayub Khan. At the heightening of sectional tensions, Mujib outlined a 6-point autonomy plan, which was seen as separatism in West Pakistan. He was tried in 1968 for allegedly conspiring with the Indian government but was not found guilty. Despite leading his party to a major victory in the 1970 elections, Mujib was not invited to form the government.

After talks broke down with President Yahya Khan and West Pakistani politician Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Mujib was arrested and a guerrilla war erupted between government forces and Bengali nationalists aided by India. An all out war between the Pakistan Army and Bangladesh-India Joint Forces led to the establishment of Bangladesh, and after his release Mujib assumed office as a provisional president, and later prime minister. Even as a constitution was adopted, proclaiming socialism and a secular democracy, Mujib struggled to address the challenges of intense poverty and unemployment, coupled with rampant corruption. Amidst rising popular agitation, he banned other political parties and declared himself president for life in 1975. After only seven months, Mujib was assassinated along with his family by a group of army officers.

Early life

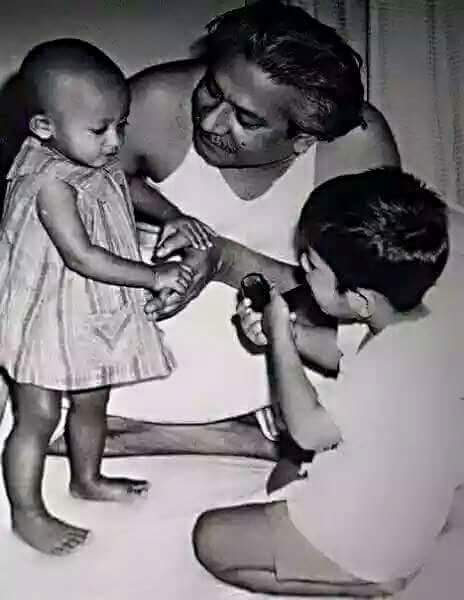

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was born in Tungipara, a village in Gopalganj District in the province of Bengal, to Sheikh Lutfar Rahman, a serestadar, or officer responsible for record-keeping at the Gopalganj civil court. He was the third child in a family of four daughters and two sons. Mujib was educated at the Gopalganj Public School and later transferred to the Gopalganj Missionary School, from where he completed his matriculation. However, Mujib was withdrawn from school in 1934 to undergo eye surgery, and returned to school only after four years, owing to the severity of the surgery and slow recovery. At the age of eighteen, Mujib married Begum Fazilatnnesa. She gave birth to their two daughters — Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana — and three sons — Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal and Sheikh Russel.

Mujib became politically active when he joined the All India Muslim Students Federation in 1940. He enrolled at the Islamia College (now Maulana Azad College), a well-respected college affiliated to the University of Calcutta in Kolkata to study law and entered student politics there. He joined the Bengal Muslim League in 1943 and grew close to the faction led by Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, a leading Bengali Muslim leader. During this period, Mujib worked actively for the League’s cause of a separate Muslim state of Pakistan and in 1946 he was elected general secretary of the Islamia College Students Union. After obtaining his degree in 1947, Mujib was one of the Muslim politicians working under Suhrawardy during the communal violence that broke out in Calcutta, in 1946, just before the partition of India.

On his return to East Bengal, he enrolled in the University of Dhaka to study law and founded the East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League and became one of the most prominent student political leaders in the province. During these years, Mujib developed an affinity for socialism as the ideal solution to mass poverty, unemployment and poor living conditions. On January 26, 1949 the government announced that Urdu would officially be the state language of Pakistan. Though still in jail, Mujib encouraged fellow activist groups to launch strikes and protests and undertook a hunger strike for 13 days. Following the declaration of Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the province chief minister Khwaja Nazimuddin in 1948 that the people of East Pakistan, mainly Bengalis, would have to adopt Urdu as the state language, agitation broke out amongst the population. Mujib led the Muslim Students League in organising strikes and protests, and was arrested along with his colleagues by police on March 11. The outcry of students and political activists led to the immediate release of Mujib and the others. Mujib was expelled from the university and arrested again in 1949 for attempting to organize the menial and clerical staff in an agitation over workers’ rights.

Early political career

Mujib launched his political career, leaving the Muslim League to join Suhrawardy and Maulana Bhashani in the formation of the Awami Muslim League, the predecessor of the Awami League. He was elected joint secretary of its East Pakistan unit in 1949. While Suhrawardy worked to build a larger coalition of East Pakistani and socialist parties, Mujib focused on expanding the grassroots organisation. In 1951, Mujib began organising protests and rallies in response to the killings by police of students who had been protesting against the declaration of Urdu as the sole national language. This period of turmoil, later to be known as the Bengali Language Movement, saw Mujib and many other Bengali politicians arrested. In 1953, he was made the party’s general secretary, and elected to the East Bengal Legislative Assembly on a United Front coalition ticket in 1954. Serving briefly as the minister for agriculture, Mujib was briefly arrested for organizing a protest of the central government’s decision to dismiss the United Front ministry. He was elected to the second Constituent Assembly of Pakistan and served from 1955 to 1958. During a speech in the assembly on the proposed plan to dissolve the provinces in favour of an amalgamated West Pakistan and East Pakistan with a powerful central government, Mujib demanded that the Bengali people’s ethnic identity be respected and that a popular verdict should decide the question:

“Sir [President of the Constituent Assembly], you will see that they want to place the word “East Pakistan” instead of “East Bengal.” We had demanded so many times that you should use Bengal instead of Pakistan. The word “Bengal” has a history, has a tradition of its own. You can change it only after the people have been consulted. So far as the question of one unit is concerned it can come in the constitution. Why do you want it to be taken up just now? What about the state language, Bengali? We will be prepared to consider one-unit with all these things. So I appeal to my friends on that side to allow the people to give their verdict in any way, in the form of referendum or in the form of plebiscite.”

In 1956, Mujib entered a second coalition government as minister of industries, commerce, labour, anti-corruption and village aid, but resigned in 1957 to work full-time for the party organization. When General Ayub Khan suspended the constitution and imposed martial law in 1958, Mujib was arrested for organising resistance and imprisoned till 1961. After his release from prison, Mujib started organising an underground political body called the Swadhin Bangal Biplobi Parishad ( Free Bangla Revolutionary Council ), comprising student leaders in order to oppose the regime of Ayub Khan and to work for increased political power for Bengalis and the independence of East Pakistan. He was briefly arrested again in 1962 for organising protests.

Leader of East Pakistan

Following Suhrawardy’s death in 1963, Mujib came to head the Awami League, which became one of the largest political parties in Pakistan. The party had dropped the word “Muslim” from its name in a shift towards secularism and a broader appeal to non-Muslim communities. Mujib was one of the key leaders to rally opposition to President Ayub Khan’s Basic Democracies plan, the imposition of martial law and the one-unit scheme, which centralized power and merged the provinces. Working with other political parties, he supported opposition candidate Fatima Jinnah against Ayub Khan in the 1964 election. Mujib was arrested two weeks before the election, charged with sedition and jailed for a year. In these years, there was rising discontent in East Pakistan over the atrocities committed by the military against Bengalis and the neglect of the issues and needs of East Pakistan by the ruling regime. Despite forming a majority of the population, the Bengalis were poorly represented in Pakistan’s civil services, police and military. There were also conflicts between the allocation of revenues and taxation.

Unrest over continuing denial of democracy spread across Pakistan and Mujib intensified his opposition to the disbandment of provinces. In 1966, Mujib proclaimed a 6-point plan titled Our Charter of Survival at a national conference of opposition political parties at Lahore, in which he demanded self-government and considerable political, economic and defence autonomy for East Pakistan in a Pakistani federation with a weak central government. According to his plan:

1. The constitution should provide for a Federation of Pakistan in its true sense on the Lahore Resolution and the parliamentary form of government with supremacy of a legislature directly elected on the basis of universal adult franchise.

2. The federal government should deal with only two subjects: defence and foreign affairs, and all other residuary subjects shall be vested in the federating states.

3. Two separate, but freely convertible currencies for two wings should be introduced; or if this is not feasible, there should be one currency for the whole country, but effective constitutional provisions should be introduced to stop the flight of capital from East to West Pakistan. Furthermore, a separate banking reserve should be established and separate fiscal and monetary policy be adopted for East Pakistan.

4. The power of taxation and revenue collection shall be vested in the federating units and the federal centre will have no such power. The federation will be entitled to a share in the state taxes to meet its expenditures.

5. There should be two separate accounts for the foreign exchange earnings of the two wings; the foreign exchange requirements of the federal government should be met by the two wings equally or in a ratio to be fixed; indigenous products should move free of duty between the two wings, and the constitution should empower the units to establish trade links with foreign countries.

6. East Pakistan should have a separate militia or paramilitary forces.

Mujib’s points catalysed public support across East Pakistan, launching what some historians have termed the 6 point movement — recognized as the definitive gambit for autonomy and rights of Bengalis in Pakistan. Mujib obtained the broad support of Bengalis, including the Hindu and other religious communities in East Pakistan. However, his demands were considered radical in West Pakistan and interpreted as thinly-veiled separatism. The proposals alienated West Pakistani people and politicians, as well as non-Bengalis and Muslim fundamentalists in East Pakistan.

Mujib was arrested by the army and after two years in jail, an official sedition trial in a military court opened. Widely known as the Agartala Conspiracy Case, Mujib and 34 Bengali military officers were accused by the government of colluding with Indian government agents in a scheme to divide Pakistan and threaten its unity, order and national security. The plot was alleged to have been planned in the city of Agartala, in the Indian state of Tripura. The outcry and unrest over Mujib’s arrest and the charge of sedition against him destabilised East Pakistan amidst large protests and strikes. Various Bengali political and student groups added demands to address the issues of students, workers and the poor, forming a larger “11-point plan.” The government caved to the mounting pressure, dropped the charged and unconditionally released Mujib. He returned to East Pakistan as a public hero.

Joining an all-parties conference convened by Ayub Khan in 1969, Mujib demanded the acceptance of his six points and the demands of other political parties and walked out following its rejection. On December 5, 1969 Mujib made a declaration at a public meeting held to observe the death anniversary of Suhrawardy that henceforth East Pakistan would be called “Bangladesh”:

“There was a time when all efforts were made to erase the word “Bangla” from this land and its map. The existence of the word “Bangla” was found nowhere except in the term Bay of Bengal. I on behalf of Pakistan announce today that this land will be called “Bangladesh” instead of East Pakistan.”

Mujib’s declaration heightened tensions across the country. The West Pakistani politicians and the military began to see him as a separatist leader. His assertion of Bengali cultural and ethnic identity also re-defined the debate over regional autonomy. Many scholars and observers believed the Bengali agitation emphasized the rejection of the Two-Nation Theory — the case upon which Pakistan had been created — by asserting the ethno-cultural identity of Bengalis as a nation. Mujib was able to galvanise support throughout East Pakistan, which was home to a majority of the national population, thus making him one of the most powerful political figures in the Indian subcontinent. It was following his 6-point plan that Mujib was increasingly referred to by his supporters as “Bangabandhu” (literally meaning “Friend of Bengal” in Bengali).

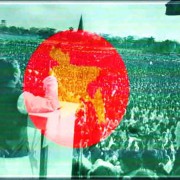

1970 elections and independence

A major coastal cyclone struck East Pakistan in 1970, leaving hundreds of thousands dead and millions displaced. The subsequent period exposed extreme outrage and unrest over the perceived weak and ineffective response of the central government. Public opinion and political parties in East Pakistan blamed the governing authorities as intentionally negligent. The West Pakistani politicians attacked the Awami League for allegedly using the crisis for political gain. The dissatisfaction led to divisions within the civil services, police and military of Pakistan. In the elections held in December 1970, the Awami League under Mujib’s leadership won a massive majority in the provincial legislature, and all but 2 of East Pakistan’s quota of seats in the new National Assembly, thus forming a clear majority.

The election result revealed a polarisation between the two wings of Pakistan, with the largest and most successful party in the West being the Pakistan Peoples Party of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, who was completely opposed to Mujib’s demand for greater autonomy. Bhutto threatened to boycott the assembly and oppose the government if Mujib was invited by Yahya Khan (then president of Pakistan) to form the next government, demanding his party’s inclusion. There was also widespread opposition in the Pakistani military and the Islamic political parties to Mujib becoming Pakistan’s prime minister. And even though neither Mujib nor the League had explicitly advocated political independence for East Pakistan, smaller nationalist groups were demanding independence for Bangladesh .

Following political deadlock, Yahya Khan delayed the convening of the assembly — a move seen by Bengalis as a plan to deny Mujib’s party, which formed a majority, from taking charge. It was on March 7, 1971 that Mujib called for independence and asked the people to launch a major campaign of civil disobedience and organised armed resistance at a mass gathering of people held at the Race Course Ground in Dhaka.

“The struggle now is the struggle for our emancipation; the struggle now is the struggle for our independence. Joy Bangla!..Since we have given blood, we will give more blood. God-willing, the people of this country will be liberated…Turn every house into a fort. Face (the enemy) with whatever you have.”

Following a last ditch attempt to foster agreement, Yahya Khan declared martial law, banned the Awami League and ordered the army to arrest Mujib and other Bengali leaders and activists. The army launched Operation Searchlight to curb the political and civil unrest, fighting the nationalist militias that were believed to have received training in India. Speaking on radio even as the army began its crackdown, Mujib declared Bangladesh’s independence at midnight on March 26, 1971:

“This may be my last message; from today Bangladesh is independent. I call upon the people of Bangladesh wherever you might be and with whatever you have, to resist the army of occupation to the last. Your fight must go on until the last soldier of the Pakistan occupation army is expelled from the soil of Bangladesh. Final victory is ours.”

Mujib was arrested and moved to West Pakistan and kept under heavy guard in a jail near Faisalabad (then Lyallpur). Many other League politicians avoided arrest by fleeing to India and other countries. Pakistani general Rahimuddin Khan was appointed to preside over Mujib’s criminal court case. The actual sentence and court proceedings have never been made public.

The Pakistani army’s campaign to restore order soon degenerated into a rampage of terror and bloodshed. With militias known as Razakars, the army targeted Bengali intellectuals, politicians and union leaders, as well as ordinary civilians. It targeted Bengali and non-Bengali Hindus across the region, and throughout the year large numbers of Hindus fled across the border to the neighbouring Indian states of West Bengal, Assam and Tripura. The East Bengali army and police regiments soon revolted and League leaders formed a government in exile in Kolkata under Tajuddin Ahmad, a politician close to Mujib. A major insurgency led by the Mukti Bahini ( Freedom Fighters ) arose across East Pakistan. Despite international pressure, the Pakistani government refused to release Mujib and negotiate with him. Most of the Mujib family was kept under house arrest during this period. His son Sheikh Kamal was a key officer in the Mukti Bahini, which was a part of the struggle between the state forces and the nationalist militia during the war that came to be known as the Bangladesh Liberation War. Following Indian intervention in December 1971, the Pakistani army surrendered to the joint force of Bengali Mukti Bahini and Indian Army, and the League leadership created a government in Dhaka. Mujib was released by the Pakistani authorities on January 8, 1972 following the official ending of hostilities. He flew to New Delhi via London and after meeting Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, he publicly expressed his thanks to “the best friends of my people, the people of India. He returned to Bangladesh on January 10, 1972. With Gandhi, he addressed a crowd of approximately half a million people gathered in Dhaka.

Governing Bangladesh

Mujibur Rahman briefly assumed the provisional presidency and later took office as the prime minister, heading all organs of government and decision-making. In doing so, he dismissed Tajuddin Ahmad following a controversial intra-party power struggle that had occurred during Mujib’s incarceration. The politicians elected in 1970 formed the provisional parliament of the new state. The Mukti Bahini and other militias amalgamated to form a new Bangladeshi army to which Indian forces transferred control on March 17. Mujib described the fallout of the war as the “biggest human disaster in the world,” claiming the deaths of as many as 3 million people and the rape of more than 200,000 women. The government faced serious challenges, which including the rehabilitation of millions of people displaced in 1971, organising the supply of food, health aids and other necessities. The effects of the 1970 cyclone had not worn off, and the state’s economy had immensely deteriorated by the conflict. There was also violence against non-Bengalis and groups who were believed to have assisted the Pakistani forces. By the end of the year, thousands of Bengalis arrived from Pakistan, and thousands of non-Bengalis migrated to Pakistan; and yet many thousands remained in refugee camps.

After Bangladesh achieved recognition from major countries, Mujib helped Bangladesh enter into the United Nations and the Non-Aligned Movement. He travelled to the United States, the United Kingdom and other European nations to obtain humanitarian and developmental assistance for the nation. He signed a treaty of friendship with India, which pledged extensive economic and humanitarian assistance and began training Bangladesh’s security forces and government personnel. Mujib forged a close friendship with Indira Gandhi, strongly praising India’s decision to intercede, and professed admiration and friendship for India. The two governments remained in close cooperation during Mujib’s lifetime.

He charged the provisional parliament to write a new constitution, and proclaimed the four fundamental principles of ” nationalism, secularism, democracy and socialism,” which would come to be known as “Mujibism.” Mujib nationalised hundreds of industries and companies as well as abandoned land and capital and initiated land reform aimed at helping millions of poor farmers. Major efforts were launched to rehabilitate an estimated 10 million refugees. The economy began recovering and a famine was prevented. A constitution was proclaimed in 1973 and elections were held, which resulted in Mujib and his party gaining power with an absolute majority. He further outlined state programmes to expand primary education, sanitation, food, healthcare, water and electric supply across the country. A five-year plan released in 1973 focused state investments into agriculture, rural infrastructure and cottage industries.

Although the state was committed to secularism, Mujib soon began moving closer to political Islam through state policies as well as personal conduct. He revived the Islamic Academy (which had been banned in 1972 for suspected collusion with Pakistani forces) and banned the production and sale of alcohol and banned the practice of gambling, which had been one of the major demands of Islamic groups. Mujib sought Bangladesh’s membership in the Organization of the Islamic Conference and the Islamic Development Bank and made a significant trip to Lahore in 1974 to attend the OIC summit, which helped repair relations with Pakistan to an extent. In his public appearances and speeches, Mujib made increased usage of Islamic greetings, slogans and references to Islamic ideologies. In his final years, Mujib largely abandoned his trademark “Joy Bangla” salutation for “Khuda Hafez” preferred by religious Muslims.

BAKSAL

Mujib’s government soon began encountering increased dissatisfaction and unrest. His programmes of nationalisation and industrial socialism suffered from lack of trained personnel, inefficiency, rampant corruption and poor leadership. Mujib focused almost entirely on national issues and thus neglected local issues and government. The party and central government exercised full control and democracy was weakened, with virtually no elections organised at the grass roots or local levels. Political opposition included communists as well as Islamic fundamentalists, who were angered by the declaration of a secular state. Mujib was criticized for nepotism in appointing family members to important positions. A famine in 1974 further intensified the food crisis, and devastated agriculture — the mainstay of the economy. Intense criticism of Mujib arose over lack of political leadership, a flawed pricing policy, and rising inflation amidst heavy losses suffered by the nationalised industries. Mujib’s ambitious social programmes performed poorly, owing to scarcity of resources, funds and personnel, and caused unrest amongst the masses.

Political unrest gave rise to increasing violence, and in response, Mujib began increasing his powers. On January 25, 1975 Mujib declared a state of emergency and his political supporters approved a constitutional amendment banning all opposition political parties. Mujib was declared “president for life,” and given extraordinary powers. His political supporters amalgamated to form the only legalised political party, the Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League, commonly known by its initials — BAKSAL. The party identified itself with the rural masses, farmers and labourers and took control of government machinery. It also launched major socialist programmes. Using government forces and a militia of supporters called the Jatiyo Rakkhi Bahini, Mujib oversaw the arrest of opposition activists and strict control of political activities across the country. The militia and police were accused of torturing suspects and political killings. While retaining support from many segments of the population, Mujib evoked anger amongst veterans of the liberation war for what was seen as a betrayal of the causes of democracy and civil rights. The underground opposition to Mujib’s political regime intensified under the clout of dissatisfaction and the government’s inability to deal with national challenges and the dissatisfaction within the Bangladeshi army.

Assassination

On August 15, 1975, a group of junior army officers invaded the presidential residence with tanks and killed Mujib, his family and the personal staff. Only his daughters Sheikh Hasina Wajed and Sheikh Rehana, who were on a visit to West Germany, were left alive. They were banned from returning to Bangladesh. The coup was planned by disgruntled Awami League colleagues and military officers, which included Mujib’s colleague and former confidanté Khondaker Mostaq Ahmad, who became his immediate successor. There was intense speculation in the media accusing the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency of having instigated the plot. Lawrence Lifschultz has alleged that the CIA was involved in the coup and assassination, basing his assumption on the then US ambassador in Dhaka Eugene Booster.

Mujib’s death plunged the nation into many years of political turmoil. The coup leaders were soon overthrown and a series of counter- coups and political assassinations paralysed the country. Order was largely restored after a coup in 1977 gave control to the army chief Ziaur Rahman. Declaring himself President in 1978, Ziaur Rahman signed the Indemnity Ordinance, giving immunity from prosecution to the men who plotted Mujib’s assassination and overthrow. Ziaur Rahman and Hossain Mohammad Ershad reversed the state’s commitment to secularism and socialism, as well as most of Mujibur Rahman’s signature policies.

In exile, Sheikh Hasina became the leader of the Awami League. She returned to Bangladesh on May 17, 1981 and led popular opposition to the military regime of President Ershad. In the elections following the restoration of democracy in 1991, Sheikh Hasina became the leader of the opposition and in 1996, she won the elections to become Bangladesh’s prime minister. Revoking the Indemnity Ordinance, an official murder case was lodged and an investigation launched. One of the main coup leaders, Colonel Syed Faruque Rahman was arrested along with 14 other army officers, while others fled abroad. Sheikh Hasina lost power in the 2001 elections, but remained the opposition leader and one of the most important politicians in Bangladesh.

Criticism and legacy

The Pakistani leadership in 1971 was considered by some observers and governments to be fighting to keep the country united in face of violent secessionist activities led by Mujib. Indian support for the Mukti Bahini dented the credibility of Mujib and the League in the community of nations. Some historians argue that the conflicts and disparities between East and West Pakistan were exaggerated by Mujib and the League and that secession cost Bangladesh valuable industrial and human resources. The governments of Saudi Arabia and China criticised Mujib and many nations did not recognise Bangladesh until after his death.

Several historians regard Mujib as a rabble-rousing, charismatic leader who galvanised the nationalist struggle but proved inept in governing the country. During his tenure as Bangladesh’s leader, Muslim religious leaders and politicians intensely criticized Mujib’s adoption of state secularism. He alienated some segments of nationalists and the military, who feared Bangladesh would come to depend upon India and become a satellite state by taking extensive aid from the Indian government and allying Bangladesh with India on many foreign and regional affairs. Mujib’s imposition of one-party rule and suppression of political opposition alienated large segments of the population and derailed Bangladesh’s experiment with democracy for many decades.

Following his death, succeeding governments offered low-key commemorations of Mujib, and his public image was restored only with the election of an Awami League government led by his daughter Sheikh Hasina in 1996. August 15 is commemorated as “National Mourning Day,” mainly by Awami League supporters. He remains the paramount icon of the Awami League, which continues to profess Mujib’s ideals of socialism. Mujib is widely admired by scholars and in Bengali communities in India and across the world for denouncing the military rule and ethnic discrimination that existed in Pakistan, and for leading the Bengali struggle for rights and liberty.

In a 2004 poll conducted on the worldwide listeners of BBC’s Bengali radio service, Mujib was voted the “Greatest Bengali of All Time” beating out Rabindranath Tagore and others.

WIKIPEDIA©