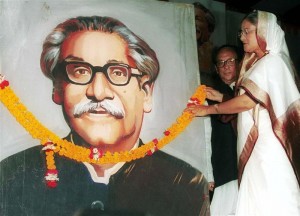

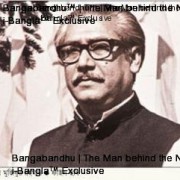

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is not just a name, an icon of freedom, an institution who portrayed the image of a most successful global leader and became voice of the people. The title of greatest man of the millennium or greatest man of Bangladesh ever lived – is not enough. His whole life symbolize of a leader who sacrificed his life for betterment of his people, of his country. His significant role entitled him as Bangabandhu, founder of Bangladesh, father of the nation and one of the most influential world leaders.

Life of the Poet of Politics:

1920

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was born in a respectable Muslim family on 17 March 1920, in Tungipara village under the then Gopalganj subdivision (at present district) of Faridpur district. He was the third child among four daughters and two sons of Sheikh Lutfar Rahman and Siara Begum. His parents used to call him Khoka out of affection. Bangabandhu spent his childhood in Tungipara.

1927

At the age of seven, Bangabandhu began his schooling at Gimadanga primary school. At nine, he was admitted to class three at Gopalganj public school. Subsequently, he was transferred to a local missionary school.

1934

Bangabandhu was forced to go for a break of study when, at the age of fourteen, one of his eyes had to be operated on.

1937

Bangabandhu returned to school after a break of four years caused by the severity of the eye operation.

1938

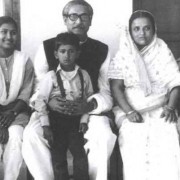

At eighteen, Mujib married Begum Fazilatnnesa. They subsequently became the happy parents of two daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, and three sons, Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal and Sheikh Russel. All the sons were to be killed along with their parents on 15 August 1975.

1939

Bangabandhu’s political career was effectively inaugurated while he was a student at Gopalganj missionary school. He led a group of students to demand that the cracked roof of the school be repaired when Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Huq, Prime Minister of undivided Bengal, came to visit the school along with Husein Shaheed Suhrawardy, later chief minister of Bangla and even later prime minister of Pakistan.

1940

Sheikh Mujib joined the Nikhil Bharat Muslim Chhatra Federation (All India Muslim Students Federation). He was elected to a one-year term.

1942

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman passed the Entrance (currently Secondary School Certificate) Examination. He then took admission as an intermediate student in the Humanities faculty of Calcutta Islamia College, where he had lodgings at Baker Hostel. That same year Bangabandhu got actively involved with the movement for the creation of Pakistan.

1943

Sheikh Mujib’s busy and active political career took off in the literal sense with his election as a councilor of the Muslim League.

1944

Bangabandhu took part in the conference of the All Bengal Muslim Students League held in Kushtia, where he played an important role. He was also elected secretary of Faridpur District Association, a Calcutta-based organization of the residents of Faridpur.

1946

Sheikh Mujib was elected General Secretary of Islamia College Students Union.

1947

Bangabandhu obtained Bachelor of Arts degree from Islamia College under Calcutta University. When communal riots broke out in the wake of the partition of India and the birth of Pakistan, Bangabandhu played a pioneering role in protecting Muslims and trying to contain the violence.

1948

Bangabandhu took admission in he Law Department of Dhaka University. He founded the Muslim Students League on 4 January. He rose in spontaneous protest on 23rd February when Prime Minister Khwaja Nazimuddin in his speech at the Legislative Assembly declared : “The people of East Pakistan will accept Urdu as their state language.”

Khwaja Nazimuddin’s remarks touched off a storm of protest across the country. Sheikh Mujib immediately plunged into hectic activities to build a strong movement against the Muslim League’s premeditated, heinous design to make Urdu the only state language of Pakistan. He established contracts with students and political leaders. On 2 March, a meeting of the workers of different political parties was held to chart the course of the movement against the Muslim League on the language issue. The meeting held at Fazlul Huq Hall approved desolation placed by Bangabandhu to form an All-Part State League age Action Council.

The Action Council called for a general strike on 11 March to register its protest against the conspiracy of the Muslim League against Bangla. On 11 March, Bangabandhu was arrested along with some colleagues while the were holding a demonstration in front of the Secretariat building. The student community of the country rose in protest following the arrest of Bangabandhu. In the face of the strong student movement the Muslim League government was forced to release Bangabandhu and other student leaders on 15 march. Following his release, the All-Party State Language Action Council held a public rally at Dhaka University Bat Tala on 16 March. Bangabandhu presided over the rally, which were soon sets upon by the police.

To protest the police action Bangabandhu immediately announced a countrywide student strike for 17 March. Later, on 19 May, Bangabandhu led a movement in support of the Dhaka University Class Four employees struggling to redress the injustice done to them by their employers. Mujib was arrested again on 11 September.

1949

Sheikh Mujib was released from jail on 21 January. Bangabandhu extended his support to a strike called by the Class Four employees of Dhaka University to press home their various demands. The university authorities illogically imposed a fine on him for leading the movement of the employees. He rejected the unjust order. Eventually, the anti-Muslim League candidate Shamsul Huq won a by-election in Tangail on 26 April, Mujib was arrested for staging a sit-in strike before the vice-chancellor’s residence. When the East Pakistan Awami Muslim League was formed on 23 June, Bangabandhu was elected its joint secretary despite his incarceration. He was released in late June. Immediately after his release, he began organizing an agitation against the prevailing food crisis. In September he was detained for violating Section 144. Later, however, he was freed.

He raised the demand for Chief Minister Nurul Amin’s resignation at a meeting of the Awami Muslim League in October. Immediately afterward, he was arrested again alone with Moulana Abdul Hamid Khan Bhashani for leading a delegation to Liaquat Ali Khan. That was towards the end of October.

1950

On the first of January, the Awami Muslim League brought out an anti-famine procession in Dhaka on the occasion of Pakistan’s Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan’s visit to the province. Once again Bangabandhu was arrested and jailed, this time for two years, for leading the demonstration.

1952

On 26 January, Khwaja Nazimuddin declared that Urdu would be the state language of Pakistan. Though still in jail, Bangabandhu managed to play a leading role in organizing a protest against this announcement. From prison he sent out a call to the State Language Action Council to obverse 21 February as Demand Day for releasing political prisoners and making Bangla the state language. He began a hunger strike on 14 February. On 21 February the student community violated Section 144 and brought out a procession in Dhaka to demand the recognition of Bangla as the state language. Police opened fire, killing in the process Salam, Barkat, Rafique, Jabbar and Shafiur, who thus became martyrs of the Language Movement. In a statement from jail, Bangabandhu condemned the police firing and registered his strong protest. He was on hunger strike for 13 consecutive days. He was moved from Dhakacentral jail to Faridpur Jail to prevent him from making contact with the organizers of the movement. He was released from jail on 26 February.

1953

On 9 July, Mujib was elected general secretary of East Pakistan Awami League at this council session. Efforts were made to forge unity among Moulana Bhashani, A.K. Fazlul Huq and Shaheed Suhrawardy with the objective of taking on the Muslim League at the general elections. To achieve this goal, a special council session of the party was called on 14 November, when a resolution to form the Jukta Front (United Front) was approved.

1954

The first general elections were held on 10 March. The United Front won 223 seas out of a total of 237, including 143 captured by the Awami League. Bangabandhu swept the Gopalganj constituency, defeating the powerful Muslim League leader Wahiduzzaman by a margin of 13,000 votes. On 15 May, Bangabandhu was given charge of the ministry of agriculture and forests when the new provincial government was formed. On 29 May, the central government arbitrarily dismissed the United Front ministry. Bangabandhu was again arrested once he landed at Dhaka airport after a flight from Karachi on 30 May. He was freed on 23 December.

1955

Bangabandhu was elected a member of the legislative assembly on 5th June. The Awami League held a public meeting at Paltan Maidan on 17th June where it put forward a 21-point program demanding autonomy for East Pakistan. On 23rd June the Working Council of the Awami League decided that this members would resign from the legislative assembly if autonomy was not granted to East Pakistan. On 25ht August Bangabandhu told Pakistan’s assembly in Karachi:

SIR, YOU WILL SEE THAT THEY WANT TO PLACE THE WORD ‘EAST PAKISTAN’ INSTEAD OF ‘EAST BENGAL’. WE HAVE DEMANDED SO MANY TIMES THAT YOU SHOULD USE BENGAL INSTEAD OF PAKISTAN. THE WORD ‘BANGAL’ HAS A HISTORY, HAS A TRADITION OF TIS OWN. YOU CAN CHANGE IT ONLY AFTER THE PEOPLE HAVE BEEN CONSULTED. IT YOU WANT TO CHANGE IT THEN WE HAVE TO GO BACK TO BENGAL AND ASK THEM WHETHER THE ACCEPT IT. SO FAR AS THE QUESTION OF ONE UNIT IS CONCERNED IT CAN COME IN THE CONSTITUTION. WHY DO YOU WANT IT TO BE TAKEN UP JUST NOW? WHAT ABOUT THE STATE LANGUAGE, BENGALI? WE WILL BE PREPARED TO CONSIDER ONE-UNIT WITH ALL THESE THINGS. SO, I APPEA TO MY FRIENDS ON THAT SIDE TO ALLOW THE PEOPLE TO GIVE THEIR VERDICT IN ANY WAY, IN THE FORM OF REFERENDUM OR IN THE FORM OF PLEDICITE.

On 21st October the party dropped the word ‘Muslim’ from its name at a special council of the Bangladesh Awami Muslim League, making the party a truly modern and secular one. Bangabandhu was reelected General secretary of the party.

1956

On 3 February, Awami League leaders, during a meeting with the Chief Minister, demanded that the subject of provincial autonomy be included in the draft constitution. On 14 July, the Awami League at a meeting adopted a resolution opposing the representation of the military in the administration. The resolution was moved by Bangabandhu. On 4 September an anti-famine procession was brought out under the leadership of Bangabandhu defying Section 144. At least three persons were killed when police opened fire on the procession in Chawkbazar area. On 16 September, Bangabandhu jointed the coalition government, assuming he charge of Industries, Commerce, Labor, Anti-Corruption and Village Aid Ministry.

1957

On 30 May, Bangabandhu resigned from the cabinet in response to a resolution of the party to strengthen the organization by working for it full-time. On 7 August, he went on an official tour of China and the Soviet Union.

1958

Pakistan’s President, Major General Iskandar Mirza, and the chief of Pakistan’s army Genera Ayub Khan, imposed martial law on 7 October and banned politics. Bangabandhu was arrested on 11 October. Thereafter, he was continuously harassed through one false case after another. Released from prison after 14 months, he was arrested again at the jail gate.

1961

Bangabandhu was released from jail after he won a writ petition in the High Court. Then he started underground political activities against the martial law regime and dictator Ayub Khan. During this period he set up an underground organization called “Swadhin Bangal Biplobi Parishad” or Independent Bangla Revolutionary Council, comprising outstanding student leaders in order to work for the independence of Bangladesh.

1962

Once again Bangabandhu was arrested under the Public Security Act on 6 February. He was freed on 18 June following the withdrawal of the four-year-long martial law on 2 June. On 25 June, Bangabandhu joined other national leaders to protest the measures introduced by Ayub Khan. On 5 July he addressed a public rally at Paltan Maid an where he bitterly criticized Ayub Khan. He went to Lahore on 24 September and joined forces with Shaheed Suhrawardy to form the National Democratic Front, an alliance of the opposition parties. He spent the entire month of October traveling across the whole of Bengal along with Shaheed Suhrawardy to drum up public support for the United Front.

1963

Sheikh Mujib went to London for consultations with Suhrawardy, who was there for medical treatment. On 5 December, Suhrawardy died in Beirut.

1964

The Awami League was revitalized on 25 January at a meeting held at Bangabandhu’s residence. The meeting adopted a resolution to demand the introduction of parliamentary democracy on the basis of adult franchise in response to public sentiment. The meeting elected Maulana Abdur Rashid Tarkabagish as party president and Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib as general secretary. On 11 March, an All-Party Action Council was formed. Bangabandhu led a committee to resist communal riots. Following the riots he took the initiative to start a vigorous anti-Ayub movement. Bangabandhu was arrested 14 days before the presidential election.

1965

The government charged Sheikh Mujib with sedition and making objectionable statements. He was sentenced to a one-year jail term. He was later released on an order of the High Court.

1966

On 5 February, a national conference of the opposition parities was held in Lahore. Bangabandhu placed his historic 6-point demand before the select committee of the conference. The 6-point demand was a palpable charter of freedom of the Bengalee nation. On the first day of March, Bangabandhu was elected president of the Awami League. Following his election, he launched a campaign to obtain enthusiastic support for the 6-point demand. He toured the entire country. During his tour he was arrested by the police and detained variously at Sylhet, Mymensingh and Dhaka several times. During the first quarter of the year he was arrested eight times. On 8 May, he was attested again after his speech at a rally of jute mill workers in Narayanganj. A countrywide strike was observed on 7 June to demand the release of Bangabandhu and other political prisoners. Police opened fire during the strike and killed a number of workers in Dhaka, Narayanganj and Tongi.

1968

The Pakistan government instituted the notorious Agartala conspiracy case against Bangabandhu and 34 Bengalee military and CSP officers. Sheikh Mujib was named accused number one in the case that charged the arrested persons with conspiring to bring about the secession of East Pakistan from the rest of Pakistan. The accused were kept detained inside Dhaka Cantonment. Demonstrations started throughout the province to demand the release of Bangabandhu and the other co-accused in the Agartala conspiracy case. The trial of the accused began on 19 June inside Dhaka Cantonment amidst tight security.

1969

The Central Students Action Council was formed on 5 January to press for the acceptance of the 11-point demand that included the 6-point demand of Bangabandhu. The council initiated a countrywide student agitation to force the government to withdraw the Agartala conspiracy case and release Bangabandhu. The agitation gradually developed into a mass movement. After months of protests, violations of Section 144 and curfews, firing by the police and the EPR and a number of casualties, the movement peaked into an unprecedented mass upsurge that forced Ayub Khan to convene a round-table conference of political leaders and announce Bangabandhu’s release on parole. On 22 February, the central government bowed to the continued mass protests and free Bangabandhu and the other co-accused. The conspiracy case was withdrawn. The Central Student Action Council arranged a reception in honor of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 23 February at the racecourse (Suhrawardy Uddyan). At this meeting of one million people, Mujib was publicly acclaimed as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal). In his speech on the occasion, Bangabandhu pledged his total support to the 11-point demand of the student.

On 26 February, Bangabandhu joined the round-table conference called by Ayub Khan in Rawalpindi. At the conference Bangabandhu placed the 6-point demand of his party and the 11-point demand of the students and said: “To end the people’s anger there is no alternative to the acceptance of the 6-point and 11-point demand and the granting of regional autonomy”. When the Pakistani politicians and rulers rejected his demand he left the conference on 13 March. The next day he returned to Dhaka. On 25 March, Gen. Yahya Khan seized power and imposed martial law. On 25 October, Bangabandhu went to London on a three-week organizational tour. On 5 December, Bangabandhu declared at a discussion meeting held to observe the death anniversary of Shaheed Suhrawardy that henceforth East Pakistan would be called Bangladesh. He added: “There was a time when all efforts were made to erase the word ‘Bangla’ from this land and its map. The existence of the word ‘Bangla’ was found nowhere except in the term Bay of Bangal. I on behalf of Pakistan announce today that this land will be called ‘Bangladesh’ instead of ‘East Pakistan.’

1970

Bangabandhu was re-elected President of the Awami League on 6 January. The Awami League at a meeting of the Working committee on 1 April decided to take part in the general elections scheduled for later that year. On 7 June, Bangabandhu addressed a public meeting at the racecourse ground and urged the people to elect his party on the issue of the 6-point demand. On 17 October, Bangabandhu selected the boat as his party’s election symbol and launched his campaign through an election rally at Dhaka’s Dholai Khal. On 28 October, he addressed the nation over radio and television and called upon the people to elect his party’s candidates to implement the 6-point demand. When a mighty cyclone storm hit the coastal belt of Bangladesh, killing at lest one million people, Bangabandhu suspended his election campaign and rushed to the aid of the helpless people in the affected areas. He strongly condemned the Pakistani rulers indifference to the cyclone victims and protested against it. He called on the international community to help the people affected by the cyclone. In the general elections held on 7 December, the Awami League gained an absolute majority. The Awami League secured 167 out of 169 National Assembly seats in the then East Pakistan and gained 305 out of 310 seats in the Provincial Assembly.

1971

On 3 January, Bangabandhu conducted the oath of the people’s elected representatives at a meeting at the Race Course ground. The Awami League members took the oath to frame a constitution on the basis of the 6-point demand and pledged to remain loyal to the people who had elected them. On 5 January, Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto, the leader of the majority party, the People’s Part, in the then West Pakistan, announced his readiness to form a coalition government at the centre with the Awami League. Bangabandhu was chosen as the leader of his party’s parliamentary part at a meeting of the National Assembly members elected from his party. On 27 January, Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto arrived in Dhaka for talks with Bangabandhu. The talks collapsed after three days of deliberations. In an announcement on 13 February, President Yahya Khan summoned the National Assembly to convince in Dhaka on 3 March. On 15 February, Bhutto announced that he would boycott the session and demanded that power be handed over to the majority parties in East Pakistan and West Pakistan. In a statement on 16 February, Bangabandhu bitterly criticized the demand of Bhutto and said, “The demand of Bhutto sahib is totally illogical. Power has to be handed over to the only majority party, the Awami League. The people of East Bengal are now the masters of power.”

On 1 March, Yahya Khan abruptly postponed the National Assembly session, prompting a storm of protest and throughout Bangladesh. Bangabandhu called an emergency meeting of the working committee of the Awami League, which called a countrywide hartal for 3 March. After the hartal was successfully observed, Bangabandhu called on the President to immediately transfer power to his party.

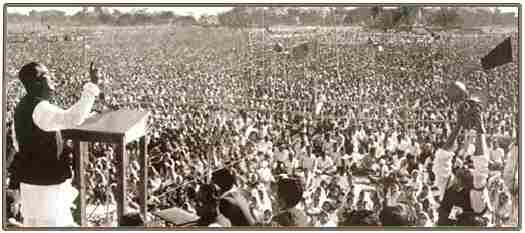

On 7 March, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed a mammoth public rally at the Race Course ground, where he declared:

“THE STRUGGLE NOW IS THE STRUGGLE FOR OUR EMANCIPATION, THE STRUGGLE NOW IS THE STRUGGLE FOR OUR INDEPENDENCE. JOI BANGLA.” IN THIS HISTORIC SPEECH, BANGABANDHU URGED THE NATION TO BREAK THE SHACKLES OF SUBJUGATION AND DECLARED, “SINCE WE HAVE GIVEN BLOOD, WE WILL GIVE MORE BLOOD. GOD-WILLING, THE PEOPLE OF THIS COUNTR WILL BE LIBERATED…. TURN EVERY HOUSE INTO A FORT. FACE (THE ENEMY) WITH WHATEVER YOU HAVE.”

He advised the people to prepare themselves for a guerilla war against the enemy. He asked the people to start a total non-cooperation movement against the government of Yahya Khan. There were ineffectual orders from Yahya Khan on the one hand, while the nation, on the other hand, received directives from Bangabandhu’s Road 32 residence. The entire nation carried out Bangabandhu’s instructions. Ever organization, including government offices, banks, insurance companies, schools, colleges, mills and factories obeyed Bangabandhu’s directives. The response of the people of Bangladesh to Bangabandhu’s call was unparalleled in history. It was Bangabandhu who conducted the administration of an independent Bangladesh from March 7 to March 25.

On 16 March, Yahya Khan came to Dhaka for talks with Bangabandhu on the transfer of power. Bhutto also came a few days later to Dhaka for talks. The Mujib-Yahya-Bhutto talks continued until 24 March. Yahya Khan left Dhaka in the evening of 25 March in secrecy. On the night of 25 March, the Pakistan army cracked down on the innocent unarmed Bangalees. They attacked Dhaka University, the Peelkhana Headquarters of the then East Pakistan Rifles and the Rajarbagh Police Headquarters.

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman read out a wireless message, moments after the crackdown began, declaring the independence of Bangladesh as 25 March gave way to 26 March. His declaration was transmitted over wireless to the country:

“THIS MAY BE MY LAST MESSAGE, FROM TO-DAY BANGLADESH IS INDEPENDENT. I CALL PON THE PEOPLE OF BANGLADESH WHEREVER YOU MIGHT BE AND WITH WHATEVER YOU HAVE, TO RESIST THE ARMY OF OCCUPATION TO THE LAST. YOUR RIGHT MUST GO ON UNTIL THELAST SOLDIER OF THE PAKISTANOCCUPATION ARMY IS EXPELLED FROM THE SOIL OF BANGLADESH. FINAL VICTORY IS OURS.”

He called upon all sections of people, including Bangalee military and civilian personnel, students, workers and peasants, to join the resistance against the occupation Pakistan army. This message of Bangabandhu was immediately disseminated throughout the country through radio equipment under special arrangements. The same night jawans and officers in Chittagong, Comilla and Jessore cantonments put up resistance to the Pakistan army after receiving this message. Bangabandhu’s declaration was broadcast by Chittagong Radio station. The Pakistanarmy arrested Bangabandhu from his Dhanmondi residence at 1-10 A.m. and whisked him away to Dhakacantonment. On 26 March he was flown to Pakistan as a prisoner. The same day, General Yahya Khan, in a broadcast banned the Awami League and called Bangabandhu a traitor.

On 26 March, M.A Hannan, an Awami League leader in Chittagong, read out Bangabandhu’s declaration of dependence over Chittagong radio. On 10 April, The Provisional Democratic Government of Bangladesh was formed with Bangabandhu as President.

The revolutionary government took the oath of office on 17 April at the Amrakanan of Baidyanathtala in Meherpur, which is now known as Mujibnagar. Bangabandhu was elected President, Syed Nazrul Islam acting President and Tajuddin Ahmed Prime Minister. The Liberation War ended on 16 December when the Pakistani occupation forces surrendered at the historic racecourse ground accepting defeat in the glorious was led by the revolutionary government in exile. Bangladesh were finally free.

Earlier, between August and September of 1971, the Pakistani junta held a secret trial of Bangabandhu inside Lyallpur jail in Pakistan. He was sentenced to death. The freedom-loving people of the world demanded absolute security of Bangabandhu’s life. Once Bangladesh was liberated, the Bangladesh government demanded that Bangabandhu be released immediately and unconditionally. A number of countries, including India and the Soviet Union, and various international organizations urged the release of Bangabandhu. Pakistan had no right to hold Bangabandhu, who was the architect of Bangladesh. In the meantime, Bangladesh had been recognized by many countries of the world.

1972

The Pakistan government freed Bangabandhu on 8 January 1972. Bangabandhu was seen off at Rawalpindi by Zulfiquar Ali Bhutto, by now Pakistan’s president the same day Bangabandhu left for London en route to Dhaka. InLondon, British Prime Minister Edward Heath met him. On his way back home from London Bangabandhu had a stop-over in New Delhi, where he was received by Indian President V. V. Giri and Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

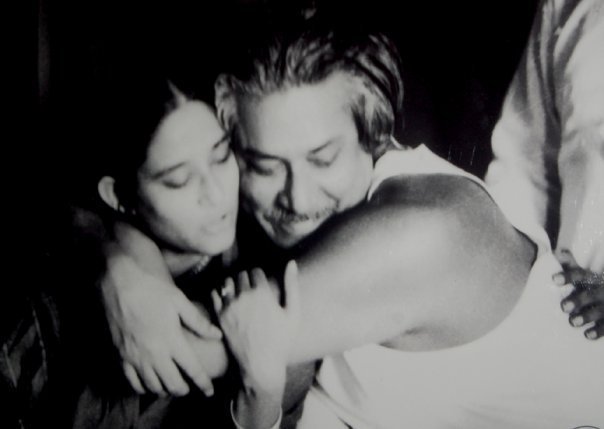

A memorable reception was accorded to Bangabandhu when the Father of the Nation reached Dhaka on 10 January. From the airport he drove straight to the Racecourse Ground where he made a tearful address before the country. On 12 January, Bangabandhu became Bangladesh’s Prime Minister. On 6 February he traveled to India at the invitation of the Indian government. After twenty-four years the Dhaka University authorities rescinded his expulsion order and accorded him the University’s life membership.

On 1 March he went to the Soviet union on an official visit. The allied Indian army left Dhaka on 17 March at the request of Bangabandhu. On 1 Ma he announced a raise in the salary of class three and four employees of the government. On 30 July Bangabandhu underwent a gall bladder operation in London. From there he went toGeneva. On 10 October the World Peace Council conferred the Julio Curie award on him. On 4 November, Bangabandhu announced that the first general election in Bangladesh would be held on 7 March, 1973. On 15 December, Bangabandhu’s government announced the provision of according state awards to the freedom fighters. On the first anniversary of liberation the constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh was framed.

Among the important achievements of the Bangabandhu government:

The reorganization of the administrative system, framing of the constitution, rehabilitation of one crore people, restoration and development of communication system, expansion of education, supply of free books to students upto class V and at low price to students upto class VIII, effective ban on all anti-Islamic and anti-social activities like gambling, horse races, drinking of liquor, establishment of Islamic Foundation, reorganization of Madrasa Board, establishment of 11,000 primary schools, nationalization of 40,000 primary schools, establishment of women’s rehabilitation centre for the welfare of distressed women, Freedom Fighters Welfare Trust, waiving tax upto 25 bighas of land, distribution of agricultural inputs among farmers free of cost or at nominal price, nationalization of banks and insurance companies abandoned by the Pakistanis and 580 industrial nits, employment to thousands of workers and employees, construction of Ghorasal fertilizer factory, primary work of Ashuganj complex and establishment of other new industrial units and reopening of the closed industries. Thus Bangabandhu successfully built an infrastructure for the economy to lead the country towards progress and prosperity. Another landmark achievement of the Bangabandhu government was to gain recognition of almost all countries of the world and the United Nations membership in a short period of time.

1973

The Awami League secured 293 out of the 300 Jatiya Sangsad (parliament) seats in the first general elections. On 3 September, the Awami League, CPB and NAP formed Oikya Front (United Front). On 6 September, Bangabandhu traveled to Algeria to attend the Non-Aligned Movement summit conference.

1974

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh was accorded membership of the United Nations. On 24 September, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman addressed the UN General Assembly in Bengali.

1975

On 25 January, the country switched over to the presidential system of governance and Bangabandhu took over as President of the republic. On 24 February, Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League, comprising all the political parties of the country, was launched. On 25 February, Bangabandhu called upon all political parties and leaders to join this national party. He felt the need for making Bangladesh a self-reliant nation by reducing dependence on foreign aid. So he overhauled the economic policies to achieve the goal of self-reliance, He launched the Second Revolution to make independence meaningful and ensure food, clothing, shelter, medicare, education and work to the people. The objectives of the revolution were: elimination of corruption, boosting production in mills, factories and fields, population control and establishment of national unity.

Bangabandhu received an unprecedented response to his call to achieve economic freedom by uniting the entire nation. The economy started picking up rapidly within a short time. Production increased. Smuggling stopped. The prices of essentials came down to within the purchasing capacity of the common man. Imbued with new hope, the people untidily marched forward to extend the benefits of independence to ever doorstep. But that condition did not last long.

In the pre-dawn hours of 15 August, the noblest and the greatest of Bengalees in a thousand years, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the architect of Bangladesh and the Father of the Nation, was assassinated by a handful of ambitious and treacherous military officers. On that day, Bangabandhu’s wife, a noble woman, Begum Fazilatunnessa; his eldest son, freedom fighter Sheikh Kamal; second son Lt. Sheikh Jamal; youngest son Sheikh Russel; tow daughters-in-law Sultana kamal and Rosy kamal; Bangabandhu’s brother Sheikh Naser; brother-in-law and agriculture minister Abdur Rab Serniabat and his daugher baby Serniabat; Arif Serniabat, grand son Sukanto Abdullah and nephew Shahid Serniabat Bangabandhu’s nephew, youth leader and journalist Sheikh Fazlul Huq Moni and his pregnant wife Arzoo Moni; Bangabandhu’s security officer Brig. Jamil and a 14-year-old boy Rintoo were killed. In all the killers slaughtered 16 members and relatives of Bangabandhu’s family.

Martial law was imposed in the country after the killing of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. Democracy was done away with and basic rights were snatched away. Thus began the politics of killing, coups and conspiracy. The people’s rights to food and vote were taken away.

There is international provision to hold trial of killers to protect human rights in the world. But unfortunately inBangladesh, a law was enacted under a martial law ordinance exempting the self-confessed killers of Bangabandhu from any trial. Having captured power illegally through a military coup, Gen. Ziaur Rahman spoiled the sanctity of the constitution by incorporating the notorious Indemnity Ordinance in the Fifth Amendment to the constitution. He rewarded the killers by providing them with jobs in Bangladesh diplomatic missions abroad. The people are suffering from lack of security as the killers, instead of being punished, have been rewarded. The Indemnity Ordinance, which is opposed to basic human rights, has to be repealed and the killers punished to restore rule of law in the country. The indemnity Ordinance was repealed by parliament only after the Awami League led by Bangabandhu’s daughter Sheikh Hasina returned to power in 1996.

August 15, 1975, is the blackest day in Bangladesh’s national life. The nation observes this day as National Mourning Day.

@bangabandhu.com.bd

Although our indebtedness to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is immense, his name had been officially proscribed for almost three decades, with the exception of those years (1996-2001) when the Awami League formed the government under the leadership of Sheikh Hasina.

Although our indebtedness to Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is immense, his name had been officially proscribed for almost three decades, with the exception of those years (1996-2001) when the Awami League formed the government under the leadership of Sheikh Hasina.

-180x180.jpg)