Bangabandhu’s finest hour . . .

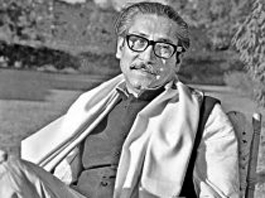

IT was his finest hour. As Bangaban-dhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman rose to speak before the million people gathered at the Race Course in Dhaka, indeed before the seventy five million people of Bangladesh on March 7, 1971, something of the electric was in the air. Over the preceding few days, reports and rumours had been making the rounds about an impending declaration of independence by the man whose party, the Awami League, had secured a clear majority of seats (167 out of a total of 313) in Pakistan’s national assembly at the general elections of December 1970.

IT was his finest hour. As Bangaban-dhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman rose to speak before the million people gathered at the Race Course in Dhaka, indeed before the seventy five million people of Bangladesh on March 7, 1971, something of the electric was in the air. Over the preceding few days, reports and rumours had been making the rounds about an impending declaration of independence by the man whose party, the Awami League, had secured a clear majority of seats (167 out of a total of 313) in Pakistan’s national assembly at the general elections of December 1970.

What should have been a journey to power as Pakistan’s prime minister on Mujib’s part had by early March 1971 been transformed into a movement for Pakistan’s eastern province to prise itself out of the state created through the division of India in 1947. The reasons were all out there. They had to do with the intrigues which had already been set in motion to thwart the assumption of power at the centre by the Awami League.

In the event, the speech Bangabandhu delivered at the Race Course served the very crucial purpose of bringing home the truth that Bangladesh was on its way to political freedom. At an intellectual level, the speech was a masterpiece. Within its parameters, Mujib deftly negotiated his way out of a bind, one in which he had found himself since President Yahya Khan had injudiciously deferred the scheduled March 3 meeting of the new national assembly in a broadcast on the first day of the month. Almost immediately, the fiery student leaders allied to the Awami League cause moved miles ahead to demand that Mujib declare Bangladesh free of Pakistan.

Over the next few days, such demands began to be echoed in other areas, eventually persuading everyone that the Bengali leader was actually about to give in to the pressure for an independence declaration. His rejection of an invitation to a round table conference called by General Yahya Khan for March 10 was seen as evidence of his intended action. Besides, there had been no perceptible move by him to restrain the students of Dhaka University when they decided to hoist the flag of what they believed would be an independent Bangladesh.

And yet those who stayed in touch with Bangabandhu, or watched the way he handled the situation in those tumultuous times, knew of the difficulties he had been pushed into. Caught between a rock and a hard place, he needed to find an acceptable, dignified way out of the crisis. On the one hand, a unilateral declaration of independence would leave him facing the charge of secessionism not only from the Pakistan authorities but also from nations around the world. He knew that as the leader of the majority party, he could not have his reputation destroyed in such cavalier manner. There were before him the poor instances of Rhodesia’s Ian Smith and Biafra’s Odumegwu Ojukwu, images he was not enthused by. Besides, any UDI would swiftly invite the retribution of the Pakistan military, at that point steadily reinforcing itself in East Pakistan.

On the other hand, Mujib realised that as undisputed spokesman of the Bengalis he was expected to provide his people with a sense of direction, one that would reassure them about the future. A recurring image is of Bangabandhu taking slow, ponderous steps as he went up to the dais on that March afternoon. It was the picture of a man with the weight of the world on his shoulders. There is every reason to believe that he was still shaping his ideas, those he would soon give expression to before that crowd of expectant Bengalis.

And then he began to speak, in oratory that was to prove once more the reality of why he had over the years scaled the heights in the politics of Bengal, of Pakistan. In that one speech he painted the entire history of why Pakistan had failed as a state. Even as he did so, he laid out his arguments in defence of what the Bengali nation needed to do. He mocked the conspiracies then afoot to deprive Bengalis of political power. With prescience, he told his people that even if he were not around, not amidst them, they should move on to protect the land, its history, from those who would trifle with it. Every moment bubbled with excitement. Bangabandhu soared, and we with him, as he defined our path to the future. The man who only minutes earlier had seemed wracked by deep worry now offered us a clear path out of the woods and into a very bright blue yonder.

“The struggle this time is the struggle for our emancipation. The struggle this time is for independence,” declaimed Bangabandhu. We cheered. We whooped for joy. We knew that he had not declared independence, but we were made aware that he had set us on the path to freedom. He had refused to be a secessionist; and he had abjured all ideas of a UDI. He had told us, in precise, unambiguous terms, that liberation was down the road, that it was a mere matter of time. We were content. As we went back home, with loud refrains of Joi Bangla around us and in our souls, we told ourselves that life for us had changed forever.

On March 7, 1971, Bangabandhu gave us reason to believe in ourselves once again. Because of him, we remembered our heritage. Because of him, we were Bengalis again. And because of him, we reached out to one another, to the world outside the one we inhabited, to build our own brave new world.

Author : Syed Badrul Ahsan, The writer is Executive Editor, The Daily Star. E-mail: bahsantareq@yahoo.co.uk