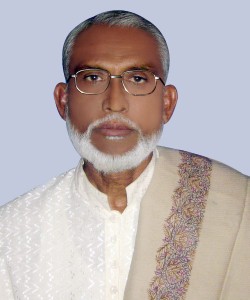

Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

The bravest son of Bangladesh. A peoples’ leader who fought all his life for their political rights and dared everything on earth to achieve independence for the Bangalees of East Bangla. The great nationalist leader of Bangladesh who voiced the demands of the nation and won the victory against the Pakistani colonists.

Declaration of Independence War of 1971

……”Pak Army suddenly attacked E.P.R Base at Pilkhana, Rajarbag Police Line and killing citizens. Street battle are going on in every street of Dhaka-Chittagong. I appeal to the Nations of the World for help. Our freedom fighters are gallantly fighting with the enemies to free the motherland. I appeal and order you all in the name of Almighty Allah to fight to the last drop of blood to liberate the country. Ask police, E.P.R, Bengal regiment and Ansar to stand by you and to fight. No compromise. Victory is ours. Drive out the last enemy from the holy soil of motherland. Convey this message to all Awami League leaders, workers and other patriots and lovers of freedom. May Allah bless you.

Joy Bangla

SK. MUJIBUR RAHMAN

Life: Mujib

| Year | Date |

Personal/Political Events |

| 1920 | Mar 17 | Born at Tungipara village in Faridpur district (presently Gopalgonj) |

| 1938 | Imprisoned for his nationalist speech in a political gathering | |

| 1940 | During a visit by the state minister Fazlul Huq and minister of food Suhrawardi to the Gopalgonj School, Sheikh Mujib, with few other students, blocked their way in demand of government initiative for the improvement of condition of the school. The leaders accepted his demands. | |

| 1946 | Elected the General Secretary of the central students’ union of Calcutta Islamia College | |

| 1947 | Formed the East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League | |

| 1947 | Nov | First use of the name “Bangladesh’ in the conference of Students’ League in Narayanganj. |

| 1949 | June 23 | Elected as the founder joint secretary of Awami Muslim League from prison. Released in July and was immediately imprisoned for hunger strike |

| 1952 | Hunger strike at Dhaka Central Jail in support of the heroes of Bangla language movement. | |

| 1953 | The responsibility of the General Secretary of Awami League was accorded to him | |

| 1954 | A new ministry was formed on 12 May 1954 by the Chief Minister Fazlul Haque and Sheikh Mujib was inducted as the youngest member of the cabinet. | |

| 1954 | May 30 | The central government dissolved Fazlul Haque’s cabinet, imposed direct rule and arrested their arch enemy, Sheikh Mujib. He was released on December 18. |

| 1955 | Sept | Turned “Muslim Awami League” into a non-communal political party by reoving the word “Muslim” from its official name. |

| 1956 | June 2 | Governor’s rule was lifted and election of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan was held in the same month. Sheikh Mujib was elected a member of the Constituent Assembly. |

| 1956 | Sept | Minister for trade, industry and anti-corruption in the ministry formed by Ataur Rahman Khan |

| 1957 | May | Resigned from the ministry in order to commit himself to organizational work for the party. |

| 1958 | October | Arrested by the military dictator General Ayub Khan on 12 false charges. |

| 1966 | Feb5, 6 | In the national conference for the opposition political parties in Lahore, Sheikh Mujib first pronounced the historic six point demands. Arrested again |

| 1968 | January | While serving long term jail sentences, the Pakistani military dictator brought charges of high treason against Sheikh Mujib. They accused Sheikh Mujib of conspiring with senior army and civil officials to overthrow the government. The trial started under a special tribunal and the case became famous as Agartala Conspiracy Case. |

| 1969 | Feb 22 | The protest against the so-called Agartala conspiracy case slowly gained momentum and the huge mass upsurge of February brought the downfall of Gen Ayub Khan and withdrawal of Agartala Conspiracy Case as well as the release of Sheikh Mujib and other co-accused. |

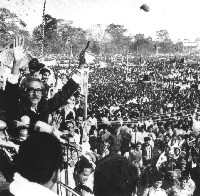

| 1969 | Feb 23 | The people gave an unprecedented reception to Sheikh Mujib and he was accorded the title “Bangabandhu”- friend of Banga (Bengal). |

| 1969 | Dec 5 | In the death anniversary of Suhrawardi, Sheikh Mujib announced that the name of the independent East Pakistan would be Bangladesh. |

| 1970 | Dec 7 | In the general election of Pakistan, Awami Leage won 167 seats out of 169 in East Pakistan. |

| 1971 | Jan 3 | Awami League inaugurated the oath of the elected members of parliament in the Race Course ground. The six points were declared a must for the people of East Pakistan |

| 1971 | Mar 3 | In protest to Gen Yahyah Khan’s deliberate refusal to hand over political power, Sheikh Mujib declared the cancellation of the session of the National Council. Under the leadership of Sheikh Mujib, all Bangalees vehemently opposed Yahya’s dictatorial intervention into national politics. |

| 1971 | March 7 | The historical speech upholding the promise for the liberation of the Bangalees……..this is our fight for liberation, this is our fight for independence………….Joy Bangla |

| 1971 | March 25 | Pakistan army unleashed its barbaric attack on the unprepared Bangalees in the dead of the night. Official declaration of independence via wireless from his residence, 32 Dhanmondi Road, just before he was captured by the Pakistani occupation forces |

| 1971 | April 17 | Formation of the Mujibnagar (provisional) government in Meherpur and Sheikh Mujib was elected the president. Syed Nazrul Islam the acting president and Tajuddin Ahmed the prime minister. |

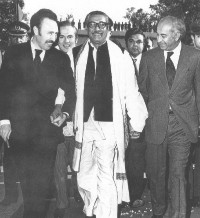

| 1972 | Jan 8 | Release from Pakistan Military custody. |

| 1972 | Jan 10 | Return to independent Bangladesh. |

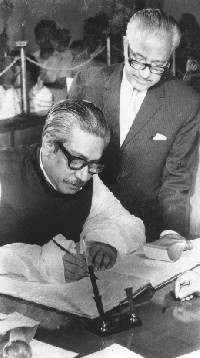

| 1972 | Jan 12 | Commencement of parliamentary democracy. Elected as the Prime Minister. Promise to presented the nation with a modern constitution in ten months. |

| 1973 | Mar 7 | General Election. Formed the government again. |

| 1973 | May 23 | Accorded the Julie Curie medal for peace |

| 1974 | Sept 28 | Address in the general assembly of the UN in Bangla |

| 1975 | Jan 25 | Formation of BKSAL (Bangladesh Krisak Sramik Awami League) for economic independence. |

| 1975 | Aug 15 | Assassinated by a band of artillery forces led by Col Faruk and Col Rashid. Many suspect CIA especially Kissinger’s involvement in the assassination of Mujib as Mujib, like Alende of Chili, defied US foreign policy formulated by Kissinger.. In the same afternoon Mujib’s body was taken straight to Tungipara, escorted by the military, his place of birth and was given a hasty burial. |

Personal Information

| Father | Sheikh Lutfur Rahman |

| Mother | Sahera Begum |

| Wife | Begum Fazilatun Nesa |

| Children | Sheikh Hasina, Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Zamal, Sheikh Rehana, Sheikh Russell |

Education

| Year | Degree | Institution |

| 1942 | SSC | The Mission High School, Faridpur |

| 1944 | HSC | Fridpur |

| 1947 | BA | Calcutta Islamia College (History & Political Science) |

| 1949 | LAW | As a student of Law Department, Dhaka university, Sheikh Mujib was arrested as he supported the strike called by the 4th class employees of Dhaka university. The university authority fined him for his involvement in worker’s politics. As Sheikh Mujib saw their strike legitimate, he refused to pay the fine and consequently was withdrawn from the university. |

Declaration of Independence

| ” Tajuddin came to my residence for shelter in that terrible night. It was, most probably, 12:45 am. With great concern Tajjuddin told me about two serious events: 1. Bangabonhu has officially declared the independence of Bangladesh and sent it to Chittagong (radio station) via wireless; 2. I implored him, holding his knees, to leave his residence and hide out, but he did not agree” |

Mr Abdul Gafur, Engineer Bangladesh Railway

“…..Before he was arrested, Sheikh Mujib made a formal declartion of independence of Bangladesh sometime between 12:00 am and 1:30 am on March 26, 1971. It was broadcast over the clandestine Swadhin Bangladesh Betar (Radio) controlled by the Mukti Fauj (freedom fighters) at noon of March 26, 1971

SK Chkrabarti: The Evolution of Politics in Bangladesh, 1947-78 (p-208)

“…The 25th of March was spent by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his party leaders in awaiting a call from General Pirzada for a final meeting with Yahya Khan and also for the final drafting session for working out the details of interim transfer of power. No such call came. At zero hours on the 26th March, the army swang into action against the unarmed people of East Pakistan, launching operation on a war scale. Meanwhile Sheikh Mujibur Rahman proclaimed the birth of sovereign Independent State of Bangladesh”

Prabodh Chandra: Bloodbath in Bangladesh, New Delhi (p-127)

“……In the night of March 25, 1971, he (Mujib) formally declared the independence of Banglaesh. This declaration was later broadcast all over the country via wireless. In the morning of March 26, 1971, I got this message at Mymensingh Agricultural university (BAU). The then Vice Chancellore of BAU, Kazi Fazlur Rahman called all the teachers, showed them Mujib’s declaration message and said: “This message came via the Mymensingh Police Line and Mr Rafiq Bhuiyan, the leader of Mymensingh Awami League, personally brought this message to me”. Immediately after the VC’s announcement, a meeting was held where Mr Bhuiyan read out the declaration of independence and recounted the dreadful Military crack down in Dhaka city the previous night….”

Shamsuz Zaman Khan (The Janakantha: 26 March, 2002)

…..” When the first shot had been fired, the voice of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman came faintly through an wavelength close to that of the official Pakistan Radio. In what must have been, and sounded like, a prerecorded message, the Sheikh proclaimed East Pakistan to be the People’s Republic of Bangladesh….”

Siddique Salik: Witness to Surrender (p.75)

Jesus of ’75

An Appeal

The killers of Sheikh Mujib haven’t killed Mujib and his family only, they axed the very foundation of the democratic system of governance. Its a blow to all civilized norms. On behalf of the people of Bangladesh Muktadhara.net appeals to the people of the world to help the government of Bangladesh to find the absconding killers of Sheikh Mujib and bring them to justice.

Copyright © muktadhara.net