I recently met an old woman passing her days by in a wheelchair. Time takes its toll on even the best of us, and looking at this eighty plus elegant lady I instinctively realized that she would like nothing better than a happy exit from our grind. I used to regularly take her comments while working at the Deutsche Welle, Germany. In the 1950s Ruqayya Jafri was an active politician, she learnt politics from Suhrawardy while on campaign trail in North Bengal. Amongst her contemporaries Shaikh Mujib was also a part of their journey.

I recently met an old woman passing her days by in a wheelchair. Time takes its toll on even the best of us, and looking at this eighty plus elegant lady I instinctively realized that she would like nothing better than a happy exit from our grind. I used to regularly take her comments while working at the Deutsche Welle, Germany. In the 1950s Ruqayya Jafri was an active politician, she learnt politics from Suhrawardy while on campaign trail in North Bengal. Amongst her contemporaries Shaikh Mujib was also a part of their journey.

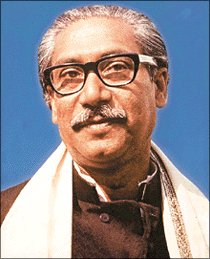

Ruqayya Jafri later became more friends with Fatema Jinnah, but her admiration for Mujib remains the same till date. They had an interesting dynamics, she would constantly suggest books to Mujib to read and persistently followed up on that reading. Even though there were times when Mujib could barely take out time from his political commitments, he would sacrifice whatever little personal time he had to read the fat volumes. It was either that or to face Ruqayya apa. That was the culture of diversity and political tolerance which Shaikh Mujib tried to maintain throughout his life. His friendships remained illuminated even when the friends chose to follow a different or adverse political cause.

Mujib never took food without ensuring the same for his team members. Ruqayya Jafri can recall so many occasions like that. In her eyes Mujib was an extraordinary man deeply in love with the soil and soul of Bengal. She is witness to several political brainstorming sessions between Mujib and his mentor Suhrawardy, always in impeccable English. To her that was the time Mujib was passionately preparing himself for a freedom flight.

During our discussion, she asked me about the impression that Mujib carries today among the masses of Bangladesh after decades for historical distortions. She didn’t need my answer as she knows the strength of the Phoenix, but she is clearly hurt by BNP’s defamation of Mujib. In all her time in Pakistan Ruqayya Jafri never saw Bhutto’s People’s Party utter a single word against Jinnah, just as defaming Gandhiji is disliked in India. She is a Bengali woman, so it’s heartbreaking for her to see her race dishonoring their Father of the Nation. Atleast for this sensitivity she still carries respect for Indians and Pakistanis.

While working as a civil servant in 1999 at the National Broadcasting House in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka, I was pleasantly surprised to find that the personal logistic staff assigned to me had served our father of the nation during his early years. It was also a matter for honor for me, so while I preferred to carry my own files, he assisted me like an ancient mariner serving me with his memories of Dhanmondi 32 Line.

To this ancient mariner Bangabandhu was an easygoing, informal man, with a sense of humor, who would often inquire about this little man’s personal wellbeing, generously tipping him whenever he could. He narrated Bangabanghu as his dream man who never took dinner without ensuring this orderly’s food, who didn’t differentiate between affections for his own children and the kids of his domestic helps.

Ruqayya Jafri in Karachi seconded the tales of this orderly, who is now in his seventies, wears specs and gazes at the sky to salute the star who always had a smile for him. This orderly withdrew from society after the killing of Dhamandi 32. He lost his position, was tortured by war criminals and his claims for getting his job back were repeatedly refused by the Jatiyo party and BNP governments. So in 1997 he got in touch with prime minister Shaikh Hasina and got his job back. But by then he had lost his concentration and even his appetite. I found him to be in a constant sense of trauma. While working for an audience program on Bangabandhu, I saw him fixing the photograph of the father of the nation with pain and tears.

In 2001 when BNP-Jamaat took over the reign, BNP cadres started ragging him. I was organizing an exit strategy for myself and in the process tried to get him a job at the Bishya Sahityo Kendra (World Literature Center, Dhaka) or some other good place like that, but he stopped me from doing do. He had lost all interest in a job. We separated on July 31, 2002, with tears and uncertainity. However, I will be ever grateful to this ancient mariner for showing me how the Phoenix rose from the ashes, and for helping me reinforce my belief in Shaikh Mujibur Rahman.

I have omitted this ancient mariner’s name deliberately to ensure his safety because he is among the few living proofs of the supermanhood of Bangabandhu.

Author : By Maskwaith Ahsan