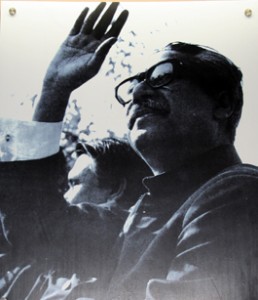

THUS CAME HOME BANGABANDHU

BANGABANDHU left home or was forced to leave by the Pakistani 0ccupation forces immediately after the ‘Operation Searchlight’ (in reality Operation Genocide) had started on the fateful night of •25 March 1971. He would remain in the Pakistani custody for the following nine agonising months. He would not know how much blood was being spilled in his Bangladesh to free the country as well as him of the occupation forces. He had to leave his country a captive; but on 10 January 1972, he returned to a hero’s welcome. What a turn-around: a captive about to be sentenced to death became free and turned hero of a country which had been occupied, but turned free! History does not bear testimony to such a turn-around having taken place in such a short span of time —that is, a liberation war fought to a successful finish within an unprecedented nine months. The day 10 January is etched in our annals as an episode not simply because Bangabandhu could return alive to lead a victorious nation; it was more so for what he got across in his home-coming address to the exultant and euphoric nation. He addressed at the same place – the Race Course, and the same pulpit from which he had delivered the historic speech of 7 March a year back. In the first speech he laid out a roadmap of liberation; and on 10 January he outlined the future of the victorious and independent state of Bangladesh. On both occasions he appeared, as it were, to fit adequately in the leadership typology as had been delineated by Winston Churchill: “The ability [of a leader] to fore-tell what is going to happen tomorrow next week, next month, and next month, and next year And to have the ability afterwards to explain why it didn’t happen.

” On 7 March 1971, — Bangabandhu foretold the inevitability of independence through a liberation war; and on 10 January he shared a blueprint for the new country the speech was extempore (as had been the case with the speech of 7 March), demonstrating the fact that although physically detached from his country and completely in the dark about the happenings back at home, he remained psychologically close to his country and people. The speech of 10 January touched upon two broad themes: state building and nation—building. These are the two tasks a newly-born state is required to address itself for charting a future for the state of Bangladesh. In retrospect, it appears that Bangabandhu had a clear vision about these two tasks as well as the challenges involved. To meet these challenges he outlined at least fifteen responses; some major ones may be drawn attention to. He began the speech by Expressing his abundant gratitude to the heroes, both fallen and alive, for freeing the country from the occupation forces. But he chirmed in with the popular exuberance as he spoke quite aloud, “I have my desire fulfilled today’ Bangladesh is free,” The following utterance was more emphatic, “I knew Bangladesh would be free;” he did know as in the 7 March speech he had said, “I would surely free the people of Bengal [Banglar] through the mercy of Allah,” and also, “No one can now keep down the people.” As to the nature and quality of the new state of Bangladesh he clearly indicated, “Bangladesh would be an ideal state; it would not be a religion-based state. The foundation of this state would be democracy socialism and religious pluralism? G am using the phrase religious pluralism for dharmanirapeksata, the word used by Bangabandhu, as I do not think This Bangla word can be translated into secularism, Etymologically and in connotation these two words are different).

The socio-economic objective of Bangladesh came out in clearest possible terms as he spoke in emotion-laden words, “I address you as a brother of yours, not president or leader that the independence would be a failure if the people do not ` get food and the young people do not get jobs — if so independence would not be complete? We have to bear in mind that he was taking upon himself as well as the people such a challenge in a country which had emerged completely war-devastated and with no resource base at all. It may be said that Bangabandhu rightly mustered the requisite courage to sensitize himself as well as his people about the enormity of challenge that lay ahead. Bangabandhu acknowledged the pro-Bangladesh role of the members of the international community He had special gratitude for the people, government of India, and their Prime Minster Indira Gandhi. He had words of gratitude for the erstwhile Soviet Union, Germany and France; but he did not have any word on China; and certainly for understandable reasons. But it is to be noted that he thanked the US people not their government; and that too for understandable reasons. He called upon all the members of the international community to extend immediate diplomatic recognition to Bangladesh. He said, “lurge all free countries of the world to recognize Bangladesh.” He also requested them to come forward with aid and assistance for his completely devastated country and demanded immediate UN membership for Bangladesh.

Bangabandhu had his own perception as to what should be done about the collaborators of genocide rape and wanton destruction. He cautioned his countrymen against taking law i.nt0 their hands and going for immediate retribution. His cautionary words were unequivocal, “Steps would be taken against them at the appropriate time. They will be put on trial; and leave this responsibility upon the government.” He also urged the people to refrain from harming the non-Bengalis who had collaborated with the Pakistani occupation forces in letting loose a reign of terror killing and destruction. His specific words were “They are also our brethren. We would demonstrate to the world that while Bengalis can sacrifice their lives for the cause of independence, they can also live in peace.” In both these cautionary utterances Bangabandhu represented the humane and tolerant Bengali psyche. A special point was made on the future •of Bangladesh’s relationship with Pakistan. As Bangabandhu addressed Pakistan: “You live in peace; but we are not with you anymore. The Bengali people would rather die than compromise on independence. I Wish you well. Accept that we are independent. You live as an independent country” Such words had a bearing on the Pakistani move for a Bangladesh-Pakistan confederation; and which was literally dismissed out of hand by Bangabandhu. Bangabandhu outlined the core principles of the would-be Bangladesh foreign policy His initial words were on the relationship with the Muslim countries, who, as we know had anti-Bangladesh role during the Liberation War but Bangabandhu, with a states- manlike foresight knew that Eventually Bangladesh would have to carve out a place in the Muslim Ummah; and this would be because of the country’s Muslim majority demo- graphic status. As he said, “Let it be known to all that Bangladesh is now the second largest Muslim state; Pakistan’s is the fourth place. Indonesia occupies the first position; and India third.” Such an astute wording of this statement pushed Pakistan as a Muslim country behind Bangladesh; and, in consequence of which, the significance of Bangladesh as a Muslim entity ` was enhanced in the eyes of the Muslim Ummah, and that was despite the country’s declared intention to be a Secular political entity this was Bangabandhu the diplomat with an eye to the future of his country ‘ The last point touched upon was the controversy as to when the Indian Army would leave Bangladesh. The sovereign status of independent Bangladesh was being questioned in some quarters of the international community because of the presence of a foreign army on its soil. But Bangabandhu assuaged any fear or suspicion when he said, “I have had words with Srimati Indira Gandhi in Delhi [about this matter]. The Indian Army would leave as and when I would desire.” The 10 January speech was supplementary to the one that had been delivered on 7 March both the speeches were future-oriented; and in which the Bangabandhu was at his best with all the qualities of a political leader and statesman.

Author : Prof. Dr. Syed Anwar Husain

(English rendering of excerpts of the speech is by the author)

Writer is editor of daily sun.