Remembering 7th March of 1971

Seminar on Speech Made by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 7th March 1971 A seminar was held on March 5, 2005 under the auspices of ‘Jatir Janak Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Memorial Trust’ at the auditorium of Institute of Engineers packed to its full capacity at 4 p.m. Three hour long seminar, participated by leading intellectuals of the country, was presided over by AL Chief Jananetri, as she is dearly called by her followers, Mrs. Sheikh Hasina, president of the memorial trust. The keynote article entitled “Bangabandhur Satoi Marcher Bhasan : Amar Aniyata Bhabna” (The 7th March Speech of Bangabandhu: My random thoughts) was presented by Professor Dr. Ajoy Roy, a physicist and our MM member. The discussants included Historian Prof. A. F. Salahuddin Ahmed, educationist Prof. Mustafa Nurul Islam, Mr. Ashrafuzzaman Khan, a nanogerian Director General (retd) of Bangladesh Radio, freedom fighter Major (retd) Rafiqul Islam, BU, Dr. Abul Barkat, professor of economics of DU, and Prof. Momtaz Latif. With non stop applause and vibrating slogans, the daughter of Bangabandhu, Sheikh Hasina entered the Hall right at 3-55 p.m. The proceedings of the seminar started immediately.

Seminar on Speech Made by Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman on 7th March 1971 A seminar was held on March 5, 2005 under the auspices of ‘Jatir Janak Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Memorial Trust’ at the auditorium of Institute of Engineers packed to its full capacity at 4 p.m. Three hour long seminar, participated by leading intellectuals of the country, was presided over by AL Chief Jananetri, as she is dearly called by her followers, Mrs. Sheikh Hasina, president of the memorial trust. The keynote article entitled “Bangabandhur Satoi Marcher Bhasan : Amar Aniyata Bhabna” (The 7th March Speech of Bangabandhu: My random thoughts) was presented by Professor Dr. Ajoy Roy, a physicist and our MM member. The discussants included Historian Prof. A. F. Salahuddin Ahmed, educationist Prof. Mustafa Nurul Islam, Mr. Ashrafuzzaman Khan, a nanogerian Director General (retd) of Bangladesh Radio, freedom fighter Major (retd) Rafiqul Islam, BU, Dr. Abul Barkat, professor of economics of DU, and Prof. Momtaz Latif. With non stop applause and vibrating slogans, the daughter of Bangabandhu, Sheikh Hasina entered the Hall right at 3-55 p.m. The proceedings of the seminar started immediately.

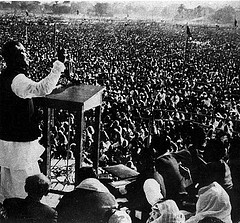

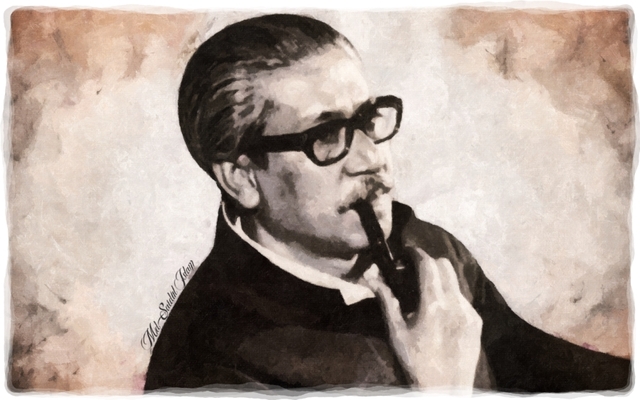

The 25-minutes duration article presented by Professor Roy set the tune of the proceedings and mood of the audience; it was presented with eloquence, emotion and solemnity demanded by the occasion- but based on facts and information and punched with recitation from the parts of historic speech of Bangabandhu delivered on March 7, 1971 in presence of not less than one million people of all cross-section of the society whom we call ‘mass’. He

stressed that speech delivered at the race course was a finest example of extempore speech ever delivered by a national leader made before an emotionally chocked mass of not less than one million. The speech emanated from the core of his heart for his people whom he loved so much. The speaker ended his with a quotation “Ekti Bangladesh, Tumi Jagrata Janatar Ekti Bangladesh, Tumi Jagrata Bismoy”

As the author finished his speech, he was greeted with non-stop applause from the emotionally chocked audience. Each of the discussants dealt some aspect of the historic speech of 7th March form different angle. As for example Prof. Barkat of economics department stressed that by the term emancipation (Mukti) in his last but most important sentence of his speech Bangabandhu meant the economic self reliance for the common men. And this could not be achieved unless the East Pakistan attained political freedom from the West Pakistani economic oppressor.

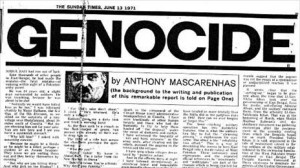

Taking part in the discussion Major (retd) Rafiqul Islam said that he took the historic speech as ‘go ahead signal’ foe all out war against Pakistani occupation. And started the war of independence when moment came- not waiting for any other call from another major. Mr. Ashrafuzzaman Khna narrated the dramatic situation when the military people surrounded the Radio broadcasting station just 10 minutes before Bangabandhu arriving at the race course. As the leader proceeded toward the microphone, the army officers ordered the radio staff not to broadcast the speech of Bangabandhu directly. Fortunately however the entire speech was tape recorded at the race course by the technicians of the Dhaka Radio station. This recorded speech was broadcast on the following day from all radio stations throughout East Pakistan. So the message of independence spread just like fire. Crores of Bengalis heard Bangabandhu clarinet call “Ebarer Sngram Amader Muktir Sabgram, Ebarer sangram Swadhinatar Sangram”

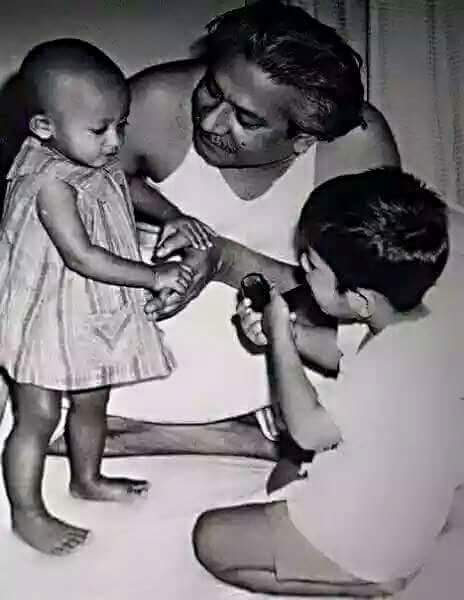

(Present struggle- struggle for our emancipation, Present struggle- struggle for independence). Mr. Khan recalled that when he informed Sheikh Mujib that his speech would be broadcast at 8-30 a.m. on March 8, he invited Mr. Khan to come to his residence so that they together listen the historic speech. And they did with Begum Mujib and other inmates of the family.

Professor Mustafa Nurul Islam evaluated the speech of Bangabandhu as one of the greatest speech ever delivered by a national leader- probably it would top the list as this speech won us the independence- a free Bangladesh. The learned professor said that at this critical hour when evil forces are engulfing Bangladesh the young generation must draw its inspiration from the speech of 7th March.

Thanking Prof. Roy, the main author of the theme of the seminar for his beautiful presentation punched with facts and figures, and other participants, the president of the seminar Sheikh Hasina winded up the discussion. In her concluding speech she urged upon the youth to be united with the spirit in which Bangabandhu urged and inspired the then youths on 7th March 34 years back to face the evil forces. Similarly the present evil forces must be met with the spirit of 7th March of seventy one, and this must be done unitedly with all forces believing in spirit of war of liberation, democracy, secularism and Bengali nationalism. Referring to the spread of terrorist fundamentalism she asked the government to arrest two Jamati ministers in the government in order to get true information about the terrorists and terrorism.