Bangabandhu after the Liberation….A Turbulent Political Career

Bangabandhu returned home on January 10, 1972 after ten months of solitary confinement in a Pakistani prison. Seventy million people of the newly liberated country had been waiting for his return since the end of the war and the subsequent surrender of the Pakistani army on the 16th of December 1971.

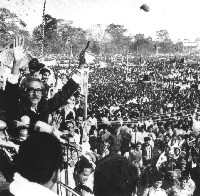

But January 10 was more than a leader’s triumphant homecoming. “Hundreds of thousands of people gathered on both sides of the streets that led to the airport. He was later taken to the Suhrawardy Uddyan; another hundreds of thousands of people gathered there just to have a glimpse of him,” Nafia Din, a student of Dhaka University during the turbulent days and now a professor of political science at a U.S. university describes the most momentous event in our political history after independence. In fact Suhrawardy Uddyan was the place where Mujib had made his last public speech, declaring civil disobedience against the Pakistani junta till the hand over of power to the legitimate representatives of the people. Ataus Samad, former correspondent of the BBC describes Mujib’s homecoming as an event that made our independence complete.

Anthony Mascarenhas, a journalist working for London based newspaper the Sunday Times who really broke the story of genocide against Bangali people internationally, writes in his book, “Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood” about Bangabandhu’s homecoming, “It was as if a human sea had been packed into the three square mile arena. Nothing like this had happened ever in Dhaka. There’s been nothing like it since then. The frenzied cheering, the extravagant praise, the public worship and obeisance were beyond the wildest day dream of any man.” But, Mascarenhas goes on “The trouble was that even before the last echoes of the cheering had faded Mujib the demi-god was brought face to face with an overwhelming reality.” Twenty million people displaced within the country plus ten million refugees who were coming home from India needed shelter, food and clothing.

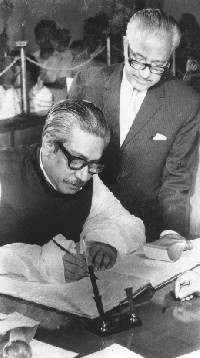

Bangabandhu affixes his signature to the draft of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh.

The country was devastated by what Mujib later called “the greatest man made disaster in history.” Topping it all was the destruction of the transport and communications systems, which made the movement of relief-supplies a daily miracle. The railway tracks and signalling equipment and rolling stock were severely damaged. Every major bridge and more than half the river transport were completely destroyed. Chittagong, one of the country’s two ports and principal entry point for food imports, was rendered unserviceable by 29 ship-wrecks blocking the Karnafulli River channel. Fewer than 1000 of the country’s 8000-truck fleet were serviceable. There was no gasoline. Bangladesh desperately needed 2.5 million tons of food to avoid famine. And when this was forthcoming from the international community it required an additional miracle to get it to the country’s 60,000 villages, Mascarenhas writes.

To make it a law and order nightmare for any government there were an estimated 3,50,000 guns with equally vast quantities of ammunition left in the hands of various self-styled ‘Bahinies’. The world’s newest nation and its fragile economy were tittering on the brink of a total collapse.

The desperation was evident in an interview Bangabandhu gave to the Sunday Times. “What do you do about the currency? Where do you get food? Industries are dead. Commerce is dead. How do you start them again? What do you do about defence? I have no administration. Where do I get one? Tell me, how do you start a country?” he remarked to his interviewer six days after the jubilant reception he received at the Suhrawardy Uddyan.

The first move he made to run the country had cost him dearly. Unlike the overwhelming numbers of army-men and members of the police, with a few honourable exceptions, the bureaucrats remained in the service of the Pakistani occupation forces. When Bangladesh became independent on December 16, 1971, they quickly jumped on the bandwagon, proclaiming their new-found nationalism. So did many other opportunistic elements who were derisively dubbed the ’16th Division’, Mascarenhas says. Mujib turned to the 16th Division in the bureaucracy to run Bangladesh. “It was one of the fundamental mistakes he made in his three and half years in the helm,” Ataus Samad says. “It has been said that Castro told him not to run an independent country with the help of officials experienced in running a colonial administration. He advised an overhaul in the administration during the Non-Aligned Summit in Algiers, in 1973, where the two met for the first and the last time. But Mujib didn’t listen to that suggestion,” Samad continues.

So about 11,00,000 government certified freedom fighters, at the very outset of the independence, felt ignored and excluded from the reconstruction of the new country. Though Mujib offered the FFs to join the armed forces, only 8,000 turned up and they were absorbed in the Jatiya Rakkhi Bahini; officially it was the national militia, in practice, it behaved like a private army of the ruling party.

Prime Minister Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in the parliament, 1973.

In contrast to the above administrative failures Bangabandhu’s government produced a very important success: a Constitution was framed on November 4, 1972, enshrining most of the noblest of principles found in any other constitution. On December 16 that year it took effect. “It was a Herculean task, and it was done, unbelievably, within a year of our independence. It was like France after the bourgeois revolution; the Constitution guaranteed every basic right of the citizens. It was the finest document of liberal democracy,” Nafia says. Democracy, socialism, nationalism and secularism were made the four basic guiding principles of the newly liberated country. Mascarenhas, too, believes Bangladesh “had a Constitution, which any country could be proud of.”

The first general election, held in 1973, in the independent Bangladesh was smooth sailing for Bangabandhu and the Awami League. In a landslide victory, the party won 307 out of the 315 of the total seats in the Jatiya Sangsad. Maulana Bhashani, the octogenarian leader of the National Awami Party saw the election result, according to a Guardian report, as “the signal for the arrival of undiluted socialism.”

On the diplomatic front Bangabandhu’s foreign policy saw some significant success. The newly independent country got diplomatic recognition from all the major powers of the world including the four veto-wielding nations( all except China’s) at the United Nation’s Security Council. Bangabandhu’s presence at the Organisation of Islam Council’s (OIC) summit meeting in the Pakistani City of Lahore was a decision only a leader of his statute could make. Farhad Mazhar, believes “Mujib went to the OIC and set up the Islamic Foundation because he could feel the pulse of the people.” And his larger than life presence at the NAM conference in Algiers gave a huge boost to the morale of this tiny nation of 70 million people. The speech he made in Bangla at the United Nations in 1974 and the international publicity that followed made Bangladesh the voice of the Third world.

However some dark cloud of failure began to gather in the independent sky of Bangladesh. The rot was setting in from within. Corruption and monopolisation of state contracts by the ruling party cliques became so rampant that an economy of nepotism, corruption and black market literally took over the economy. Political oppression on Shiraz Sikdar revealed the autocratic nature of the highly personalised government run by Bangbandhu. The breaking out of JSD from within the ranks of Awami League clearly revealed the breach within ruling party ranks.

By this time Bangladesh was facing a new menace that had almost crippled its already fragile economy. It was smuggling. Tony Hagen, then head of the UN Relief Operation to Dhaka, aptly described the situation to the Sunday Times“Bangladesh is like a bridge suspended in India.” Some unscrupulous businessmen and officials smuggled, almost all they could, to the neighbouring country. According to some reports the smuggling of goods across the border during the first three years cost the country’s economy about Tk. 60,000 million. The goods that were smuggled were mostly food-grains, jute and materials imported from abroad. In fact by December 1973, the economy was completely bankrupt, and about 2-billion US dollars of international aid had already been injected to the country’s economy. Some of these “unscrupulous businessmen and office bearers” were Awami Leaguers; and though, the whole party was in no way collectively responsible for the smuggling, Nafia Din believes, “ Some of their involvement in smuggling and the ’25-years treaty’ with India gave the Awami League a pro-India label.”

Then came the flood of 1974. Smuggling coupled with corruption and sheer nepotism in food distributions had turned the natural disaster into a man-made calamity. Bangabandhu publicly admitted the death of 27,000 people of starvation. Mascarenhas believes the death toll “of the (subsequent) famine was well into the six figures.”

Bangabandhu wanted to make Bangladesh “the Switzerland of the east.” Nonetheless when the Rakkhi Bahini was raised to 25,000 men with basic military training and modern automatic weapons, the discontent amongst some army men turned into antagonism. “Most people wanted to see a Che Guevara out of Sheikh Mujib, but certainly he wasn’t Che,” says Farhad Mazhar. Mazhar thinks that because he wasn’t a revolutionary like Che or Castro, Mujib couldn’t make any people’s army after the independence like Castro did in Cuba after the liberation; which he believes the country at that moment desperately needed.

Bangabandhu, in the name of socialism, without giving the local entrepreneurs a level playing filed, nationalised all the industries in the name of a ‘planned and controlled economy’. Ataus Samad believes Mujib’s economic policy “had demolished the entrepreneurship skill of the Bangalis.”

“Corruption, cronyism, sycophancy and political repression had virtually isolated Bangabandhu from the people by then,” observes Nafia. Bangabandhu himself told the press that almost 4000 of his party workers, including 5 MPs had been killed by numerous self-styled political factions. In November that year, Tajuddin Ahmed, who led the nation on behalf of Bangabandhu and tipped as Mujib’s natural successor, publicly criticised the government for corruption and mismanagement. In a move that may be termed as suicidal for Sheikh Mujib, he asked Tajuddin to resign who readily complied and retired from politics for the moment. As the situation got worse and Bangabandhu became more isolated, on December 28, 1974 he declared a state of emergency and on January 25, 1975 he was sworn in as the President. On June 7 that year the one party state was formed.

BKSAL (Bangladesh Krishok Sramik Awami League), now the only legitimate political party, was officially described as the “Second Revolution.” But in effect it made Bangladesh a one party state with every political and administrative power personally vested in Sheikh Mujib. The promulgation says: “When the national party is formed a person shall:

a) In case he is a member of Parliament on the date the National party is formed, cease to be such a member, and his seat in Parliament shall become vacant if he does not become a member of the National Party within the time fixed by the President

b) Not be qualified for election as President or as a Member of Parliament if he is not nominated as a candidate for such election by the National Party.

c) Have no right of form, or to be a member or otherwise take part in the activities of any political party other than the National Party.”

Bangabandhu handpicked 61 men, which included many serving bureaucrats, as District Governors, to run the country. These non-elected “Governors” were to control the Bangladesh Rifles, the Rakkhi Bahini, police and army units stationed in their respective areas from September 1. Thus the man who led his country towards independence and freedom, within four years after its independence turned it into a monolithic and one party state. Through promulgating BKSAL all newspapers, except four under government control , were closed.

But the worst was yet to come for this infant nation wobbling on its independent feet. On August 15, 1975, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was killed, along with 13 members of his family, by a bunch of disgruntled army officers, under the political leadership of Khondokar Mushtak Ahmed.It was the most gruesome political assassination that continues to haunt the nation even today.

On that fateful night a group of killers led by ex-Major Noor and Major Mohiuddin, along with a group of mutineers from the Bengal Lancers, went to the private house at Dhanmandi to kill Bangabandhu. Ex-Major Noor fired a burst from his Sten gun on the right side of Bangabandhu; his whole body twisted backwards and then it slipped to the landing space of the stairs. It was 5:40 in the morning. Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman died at an age of 56, at his home, from where he had led his people to independence. Begum Mujib was killed a moment later in front of their bedroom. Then the mayhem began. Sheikh Kamal and Sheikh Jamal, Bangabandhu’s two sons and their newly wed wives were killed. Sheikh Nasir, Mujib’s brother, who had allegedly amassed a heavy fortune during that period, was also killed. The self styled saviours of the people then killed Mujib’s 7-year old son, Sheikh Russell.

By this time another killer team, according to Mascarenhas, led by major Dalim went to Abdur Rab Serniabat’s house. In a 20-minute long massacre that followed, Serniabat was killed along with his wife, daughters and 3 minor members of the family. Serniabat’s son Abul Hasnat, a survivor in the family who had luckily escaped on that frightful night, according to Mascarenhas, “(later) saw his wife, mother and 20-year-old sister badly wounded and bleeding. His two young daughters, uninjured, were sobbing behind a sofa where they had hidden during the massacre. Lying dead on the floor were his 5-year-old son, two sisters aged 10 and 15 and his 11-year old brother, the family ayah (maid), a house-boy and his cousin Shahidul Islam Serniabat.”

Bangladesh Krishak Sramik Awami League (BKSAL), a national front comprising major political parties and professional groups of the country was formed in 1975. People are seen attending the first conference.

The attack on Sheikh Moni’s house was, to quote Mascarenhas, “Brief and devastating.” Risaldar Muslehuddin led the killers to the house of Sheikh Moni, which was also at Dhanmandi. Moni’s seven months pregnant wife jumped in front of her husband, in an attempt to save him from the Risaldar’s bullet. Both were killed by a single bullet.

Khandakar Moshtaque Ahmed who declared himself as the president on August 15 following Bangabandhu’s brutal assassination, promulgated, on 26th September, an ordinance indemnifying the killers. The Ordinance was promulgated, as the Bangladesh Gazette dated that day says, “ to restrict the taking of any legal or other proceedings in respect of certain acts or things in connection with, or in preparation or execution of any plan for, or steps necessitating, the historical change and the Proclamation of Martial Law on the morning of 15th August, 1975.”

The August 15 killing and the Indemnity Ordinance had encouraged several successful and unsuccessful coup attempts later in the army. The killers were later awarded with high-ranking government jobs by the subsequent military governments that came as a natural by-product of the August 15 mayhem. The Ordinance, which was turned into an act and incorporated in our Constitution by General Ziaur Rahman who succeeded to power in November ’75 was scrapped in the late 1996 when Awami League came to power. The trial was held under the ordinary law of the land and after several years of legal proceedings verdict was given on this historic case. It is now under appeal at the highest court.

Author : AHMEDE HUSSAIN /