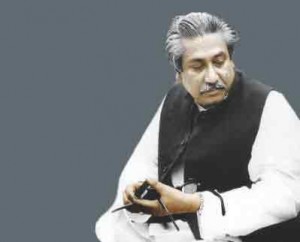

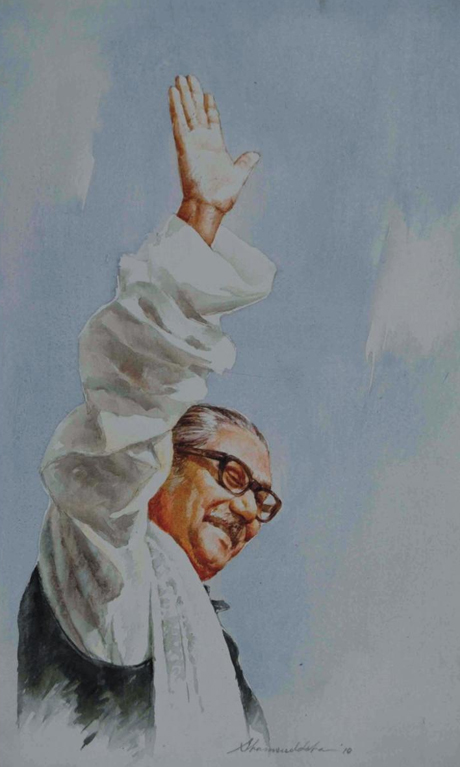

Father of the Nation Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman

He is not a mere individual. He in an institution. A movement. A revolution. An upsurge. He is the architect of the nation. He is the essence of epic poetry and he is history. This history goes back a thousand years. Which is why contemporary history has recognized him as the greatest Bengali of the past thousand years. The future will call him the superman of eternal time. And he will live, in luminosity reminiscent of a bright star, in historical legends. He will show the path to the Bengali nation his dreams are the basis of the existence of the nation. A remembrance of him is the culture and society that Bengalis have sketched for themselves. His possibilities, the promises thrown forth by him, are the fountain-spring of the civilized existence of the Bengalis.

He is not a mere individual. He in an institution. A movement. A revolution. An upsurge. He is the architect of the nation. He is the essence of epic poetry and he is history. This history goes back a thousand years. Which is why contemporary history has recognized him as the greatest Bengali of the past thousand years. The future will call him the superman of eternal time. And he will live, in luminosity reminiscent of a bright star, in historical legends. He will show the path to the Bengali nation his dreams are the basis of the existence of the nation. A remembrance of him is the culture and society that Bengalis have sketched for themselves. His possibilities, the promises thrown forth by him, are the fountain-spring of the civilized existence of the Bengalis.

He is a friend to the masses. To the nation he is the Father. In the view of men and women in other places and other climes, he is the founder of sovereign Bangladesh. Journalist Cyril Dunn once said of him, “In the thousand – year history of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujib is the only leader who has, in terms of blood, race, language, culture and birth, been a full – blooded Bengali. His physical stature was immense. His voice was redolent of thunder. His charisma worked magic on people. The courage and charm that flowed from him made him a unique superman in these times.”Newsweek magazine has called him the poet of politics.

The leader of the British humanist movement, the late Lord Fenner Brockway once remarked, “In a sense, Sheikh Mujib is a great leader than George Washington, Mahatma Gandhi and De Valera.” The greatest journalist of the new Egypt, Hasnein Heikal (former editor of Al Ahram and close associate of the late President Nasser) has said, “Nasser is not simply of Egypt. Arab world. His Arab nationalism is the message of freedom for the Arab people. In similar fashion, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman does not belong to Bangladesh alone. He is the harbinger of freedom for all Bangalis. His Bengali nationalism is the new emergence of Bengali civilization and culture. Mujib is the hero of the Bengalis, inn the past and in the times that are.

Embracing Bangabandhu at the Algiers Non – Aligned Summit in 1973, Cuba’s Fidel Castro noted, “I have not seen the Himalayas. But I have seen Sheikh Mujib. In personality and in courage, this man is the Himalayas. I have thus had the experience of witnessing the Himalayas.

Upon hearing the news of Bangabandhu’s assassination, former British Prime Minister Harold Wilson wrote to a Bengali Journalist, “This is surely a supreme national tragedy for you. For me it is a personal tragedy of immense dimensions.” Refers to the founder of a nation-state. In Europe, the outcome of democratic national aspirations has been the rise of modern nationalism and the national state.

Those who have provided leadership in the task of the creation of nations or nation-states have fondly been called by their peoples as founding fathers and have been placed on the high perches of history. Such is the reason why Kamal Ataturk is the creator of modern Turkey. And thus it is that Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman is the founder of the Bengali nation – state and father of the nation of his fellow Bengalis. But in more ways than one, Sheikh Mujib has been a more successful founding father than either Ataturk or Gandhi. Turkey existed even during the period of the Ottoman Empire. Once the empire fell, Ataturk took control of Turkey and had it veer away from western exploitation through giving shape to a democratic nation – state.

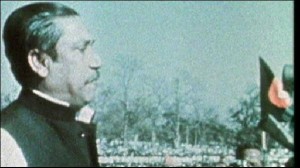

In Gandhi’s case, India and Indians did not lose their national status either before or after him. But once the British left the subcontinent, the existence of the Bengali nation appeared to have been blotted out. The new rulers of the new state of Pakistan called Bangladesh by the term “East Pakistan” in their constitution. By pushing a thousand – year history into the shadows, the Pakistani rulers imposed the nomenclature of “Pakistanis” on the Bengalis, so much so that using the term “Bengali” or “Bangladesh” amounted to sedition in the eyes of the Pakistani state. The first man to rise in defense of the Bengali, his history and his heritage, was Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. On 25 August 1955, he said in the Pakistan Constituent Assembly, “Mr. Speaker, they ( government) want to change the name of East Bengal into East Pakistan. We have always demanded that the name ‘Bangla’ be used. There is a history behind the term Bangla. There is a tradition, a heritage, If this name is at all to be changed, the question should be placed before the people of Bengal: are they ready to have their identity changed?”

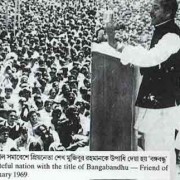

Sheikh Mujib’s demand was ignored. Bangladesh began to be called East Pakistan by the rulers. Years later, after his release from the so – called Agartalas case, Sheikh Mujib took the first step toward doing away with the misdeed imposed on his people. On 5 December 1969, he said, “At one time, attempts were made to wipe out all traces of Bengali history and aspirations. Except for the Bay of Bengal, the term Bengal is not seen anywhere. On behalf of the people of Bengal, I am announcing today that henceforth the eastern province of Pakistan will, instead of being called East Pakistan, be known as Bangladesh.” Sheikh Mujib’s revolution was not merely directed at the achievement of political freedom. Once the Bengali nation – state was established, it become his goal to carry through programmes geared to the achievement of national economic welfare.

The end of exploitation was one underlying principle of his programme, which he called the Second Revolution. While there are many who admit today that Gandhi was the founder of the non – violent non – cooperation movement, they believe it was an effective use of that principle which enabled Sheikh Sheikh Mujib to create history. Mujib’s politics was a natural follow – up to the struggle and movements of Bengal’s mystics, its religious preachers, Titumir’s crusade, the Indigo Revolt, Gandhiji’s non – cooperation, and Subhash Chandra Bose’s armed attempt for freedom. The secularism of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, the liberal democratic politics of Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Hague and Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy Contributed to the molding of the Mujib character.

He was committed to public welfare. Emerging free of the limitations of western democracy, he wished to see democracy sustain Bengali nationalism. It was this dream that led to the rise of his ideology. At the United Nations, he was the first man to speak of his dreams, his people’s aspiration, in Bangla. The language was, in that swift stroke of politics, recognized by the global community. For the first time after Rabindranath Tagore’s Nobel achievement in 1913, Bangla was put on a position of dignity. The multifaceted life to the great man cannot be put together in language or color. The reason is put on; Mujib is greater than his creation. It is not possible to hold within the confines of the frame the picture of such greatness. He is our emancipation – today and tomorrow. The greatest treasure of the Bengali nation is preservation of his heritage, a defense of his legacy. He has conquered death. His memory is our passage to the days that are to be.

Abdul Gaffar Choudhury