bangabandhu.com.bd : Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and other members of Bangabandhu family, who were in Pakistani captivity even until a day after the December 16 Victory, were exposed to high risks of being massacred by frightened enemy guards, as last casualty of 1971, two crucial witnesses said.

“The Pakistani soldiers guarding the house were looked frightened but arrogant . . . visibly they were unaware of the surrender even on that morning of December 17,” one of the top Bangabandhu aides, Hazi Golam Morshed, told BSS in an interview coinciding with the Victory Day anniversary.

Morshed, now 85, was the man who escorted the four-man squad of Indian soldiers led by gallantry award winning Major Ashok Tara to the house at road number 18 of Dhanmandi where Begum Mujib, Sheikh Russel, Sheikh Rehana and Sheikh Hasina and her newborn son were in captivity at that moment.

“Major Tara approached the (Pakistani) soldiers in bare hands keeping his weapon to his men behind . . . One of the guards shouted, asking him not to proceed a single step further if he wanted to avoid being shot,” he recalled. Morshed described the subsequent few minutes to be highly delicate as it appeared that the “frustrated, frightened and directionless” Pakistani guards were going to kill the Bangabandhu family. In separate media interviews, Tara, 29, at that time, supplemented him saying from a close distance he also understood how the captive inmates of the house were desperately seeking to be rescued sensing the Pakistani guards could kill them all.

“It was a very sensitive and important operation, and had anything gone wrong, it would have brought a very bad name to the Indian government and the Indian Army,” recalled Tara, now 71, whom Bangladesh honoured conferring the “Friend of Bangladesh” award on him two years ago.

Morshed happened to be also the last man to accompany Bangabandhu until the Pakistani troops invaded his 32 Dhanmandi residence on the black night of March 25 and himself too was arrested to languish in Dhaka cantonment and subsequently in Dhaka Central Jail until November 25. On his release he found out that Bangabandhu’s family was detained in that house at Road No 18 of Dhanmandi, heavily guarded by the Pakistani troops even on December 17 morning, a situation that prompted him to bring to the notice of the allied force about their captivity.

“I heard that the Indian army has setup a (makeshift) camp at the Circuit House in Kakrail . . . my cousin Engineer Abu Elias Majid, now staying in the United States, drove me there in his car and we found Major General BF Gonzales sitting on a chair on the veranda,” Morshed recalled. After some initial conversation, he said, the Indian general asked him if we had any car with us and getting an affirmative reply he wanted a lift to the airport, which was being guarded by Indian soldiers to secure VIP movements with Tara being their commander.

“Gonzales introduced me to Tara and then entrusted him with the task of rescuing the Bangabandhu family,” Morshed recalled. According to Morshed, the Indian troops right that moment did not have vehicles at the scene and therefore they had to approach a Bengali gentleman who happened to be there with a car and driver and “the man instantly agreed to lend his car for the rescue mission”.

“Tara got onboard in our car driven by my cousin while three Indian soldiers including a JCO (junior commissioned officer) followed us in the other car,” he said. As the two cars reached near the house a crowd stopped them and cautioned Tara about the situation pointing towards a bullet-ridden car near the house with its unknown dead driver inside, whom they killed overnight apparently due to fright or nervousness. They also told him that on the previous night they also killed five people including a woman as they were passing by the house. Tara then came out of the car and handed his sten gun over to the JCO and asked his three men to stay on one side of the road and began a slow walk to the house when a sentry on the rooftop warned him that he would be shot if he took another step further being visibly confused seeing the Indian army appearance at the scene.

“See, I am an Indian Army officer standing unarmed in front of you . . . If I have reached unarmed in front of you, it means your army has surrendered, you can ask your officer,” Tara recalled shouting back in a mix of Punjabi and Hindi. After few moments the Pakistani havildar shouted back saying “I have no contact with the officer”. The Indian major recalled that he later came to know that a Pakistani captain had abandoned his post and the news of the surrender had not yet reached the lower ranks as communications were disrupted. Incidentally at that time, he said, few Indian helicopters flew overhead and “I pointed to them and shouted — look our helicopters are flying in the sky and look behind me, our jawans are inside Dhaka”. Tara again started walking slowly towards the house telling the guards “you have a family with children as I do; if you lay down your arms and come out peacefully, I guarantee you a safe passage to your camp or wherever you want to go to”. But as he reached the entrance a young Pakistani soldier aged only about 18 appeared from the bunker at the gates pointed his rifle at him.

“The young boy was shivering. It was probably the first time he saw an Indian army officer at such close quarters . . . I locked eyes with the boy even as I was talking to the havildar on the rooftop . . . I kept up the conversation and softly pushed the barrel of the gun away from my body,” he said. Tara, a Bengali who retired as a highly decorated colonel of Indian army later said the conversation lasted for about 10 minutes when he spoke to the captors in fluent Hindi and Punjabi and the tense situation was finally dispelled without any casualties.

“And as soon as I entered the house, (Bangabandhu) Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s wife hugged me and said I was her son sent by God from the heaven (to save the family),” he recalled. Tara also recalled that an Indian newspaper later commented “the release of Begum Mujibur Rahman along with the other family members has been as thrilling as the fall of Dacca or for that matter the liberation of Bangladesh”.

“Many a time I thought that neither I nor the Indian officer (Tara) will survive this. It is a new lease of life for us,” the report quoted Begum Mujib as saying later in an interview. Tara remembered that inside the house, there was barely any furniture and the family had been sleeping on the floor and “there were hardly enough rations either . . . I saw only biscuits”.

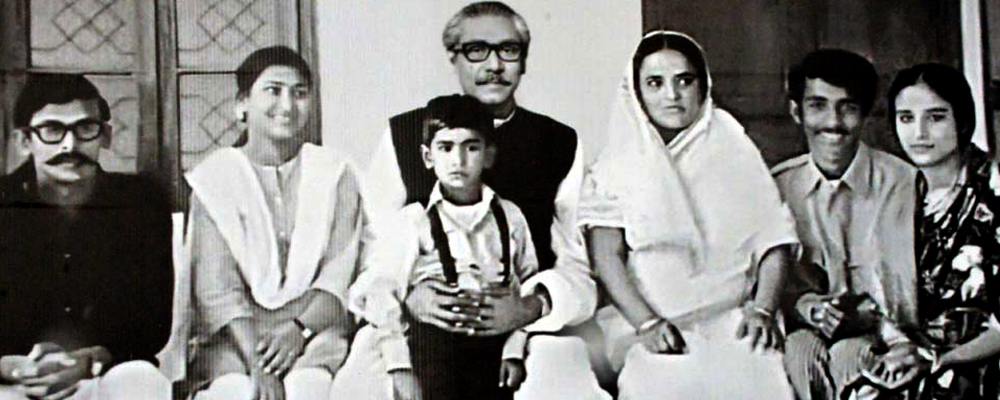

Tara recalled clicking a picture of the 24-year-old Sheikh Hasina with her baby in her arms. The Pakistani troops tracked Bangabandhu family down from a house in Moghbazar area few days after the war began and his elder son Sheikh Kamal joined the Liberation War in the first chance as he left 32 Dhanmandi hours ahead of the March 25 crackdown. His younger brother Sheikh Jamal later also managed to escape the makeshift Dhanmandi jail and eventually joined the resistance, while the rest of the family members were detained until December 17 and for the last two days Sheikh Hasina’s nuclear scientist husband also could not enter the house where he too was staying with the family. A would be mother Sheikh Hasina was in her advance stage, deprived of proper food and care required during the pregnancy and she was eventually allowed to be admitted at a hospital but her mother was debarred from accompanying her.

“When my mother wanted to come with me, the (Pakistani troops) was plainly told her ‘what you will do in the hospital? There are nurses and doctors in hospital. Are you a nurse or a doctor? You can’t go.”

“When my mother told them being the mother I want to stay beside my daughter to give her courage. But her appeal carried no value to them,” Sheikh Hasina later wrote in an article recalling her critical those days in 1971. Sheikh Hasina’s son – Sajib Wajed Joy — was born on July 27, 1971. She named her “Joy” which in Bangla means “victory”, in line with the desire of her father during her early days of pregnancy as the nation was heading towards the Liberation War.

By Anisur Rahman

The Day make the victory completeমে 10, 2019 - 8:43 অপরাহ্ন

The Day make the victory completeমে 10, 2019 - 8:43 অপরাহ্ন “Bangabandhu” – An illustrious leaderমার্চ 30, 2018 - 8:06 অপরাহ্ন

“Bangabandhu” – An illustrious leaderমার্চ 30, 2018 - 8:06 অপরাহ্ন Unesco recognises Bangabandhu’s 7th March speechঅক্টোবর 31, 2017 - 12:15 অপরাহ্ন

Unesco recognises Bangabandhu’s 7th March speechঅক্টোবর 31, 2017 - 12:15 অপরাহ্ন National Mourning Day observedআগস্ট 16, 2016 - 12:39 পূর্বাহ্ন

National Mourning Day observedআগস্ট 16, 2016 - 12:39 পূর্বাহ্ন National Mourning Day todayআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 1:43 অপরাহ্ন

National Mourning Day todayআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 1:43 অপরাহ্ন Bangabandhu had no illusions about Pakistanisআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 12:44 পূর্বাহ্ন

Bangabandhu had no illusions about Pakistanisআগস্ট 15, 2016 - 12:44 পূর্বাহ্ন HIS GREATNESS CANNOT BE TARNISHEDএপ্রিল 14, 2015 - 8:03 অপরাহ্ন

HIS GREATNESS CANNOT BE TARNISHEDএপ্রিল 14, 2015 - 8:03 অপরাহ্ন THE STORY OF AN INSPIRATIONAL FIGUREজানুয়ারি 17, 2014 - 2:20 অপরাহ্ন

THE STORY OF AN INSPIRATIONAL FIGUREজানুয়ারি 17, 2014 - 2:20 অপরাহ্ন The Declaration of Independenceজুন 6, 2013 - 5:49 অপরাহ্ন

The Declaration of Independenceজুন 6, 2013 - 5:49 অপরাহ্ন The day they killed Bangabandhuজুন 6, 2013 - 5:34 অপরাহ্ন

The day they killed Bangabandhuজুন 6, 2013 - 5:34 অপরাহ্ন