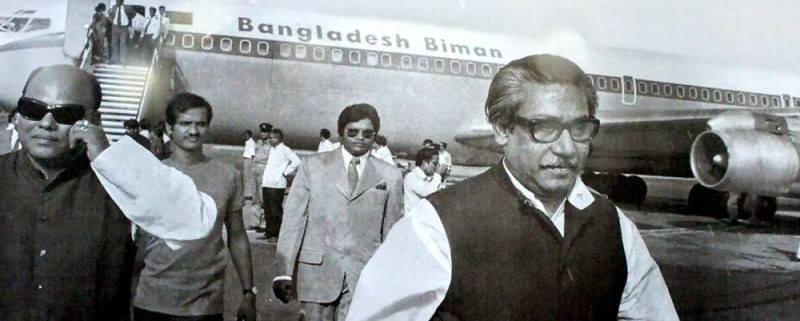

Bangabandhu at the helm and 1972

I will recall the historic role that he played as the master helmsman during 1972 and how he safely guided our ship through troubled waters amidst a devastated post-war scenario. I will do so because many have forgotten his significant role and his commitment towards democracy and institution building.

I will recall the historic role that he played as the master helmsman during 1972 and how he safely guided our ship through troubled waters amidst a devastated post-war scenario. I will do so because many have forgotten his significant role and his commitment towards democracy and institution building.

I was fortunate to meet Bangabandhu in Hotel Claridge’s in London after his arrival from Pakistan. I was there at that time on political asylum after having arrived in that city from my previous place of posting in the Pakistan Embassy in Cairo, Egypt. I had met him many times before, but this time it was totally different. It was an overpowering experience, listening to him and his plans for Bangladesh. Consequently, when he asked me if I wanted to stay on in London in the Bangladesh Mission or come to Bangladesh and help build the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, I had no hesitation in answering that it would be a privilege to be in Dhaka, in his proximity, and be able to contribute towards the creation of the new Ministry of Foreign Affairs under his guidance. He immediately agreed and gave the necessary orders for arrangements to be made so that I could return to Dhaka. I joined our Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the last week of January 1972.

A charismatic leader, dedicated and committed to the cause of Bangladesh, he encapsulated his vision for his new country at Palam Airport, New Delhi on January 10, 1972. He described his journey to a free Bangladesh as “a journey from darkness to light, from captivity to freedom, from desolation to hope.”

A statesman, a gifted orator, Bangabandhu, quite naturally was overwhelmed with emotion after setting foot for the first time in independent Bangladesh. His speech delivered on January 10 at Suhrawardy Uddyan (within a few hours of his arrival) was masterly in its pragmatic approach and in the advice for the victorious people of Bangladesh. At this first opportunity, he did not fail to warn that no one should “raise” their “hands to strike against non-Bangalees.” At the same time, he displayed his concern for the safety of the “four hundred thousand Bangalees stranded in Pakistan.” While re-affirming that he harboured no “ill-will” for the Pakistanis, he was also clear in pointing out that “those who have unjustly killed our people will surely have to be tried.”

In another significant assertion in the same speech, he pointed out to the Muslim world (to counter false and contentious Pakistani propaganda that Bangladesh had ceased to believe in Islam) that “Bangladesh is the second largest Muslim state in the world, only next to Indonesia.” He also drew their attention to the fact that “in the name of Islam, the Pakistani army killed the Muslims of this country and dishonoured our women. I do not want Islam to be dishonoured.” He also appealed to the United Nations to “constitute an International Tribunal to enquire and determine the extent of genocide committed in Bangladesh by the Pakistani army.”

The above views were inter-related, and demonstrated his determination not only to hold a war crimes trial but also to point out that Islam had been abused by the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. It was also this outlook that led him later on to strongly express his regret on February 10, 1972 (in a message sent to Tenku Abdur Rahman, Secretary General of the Organisation of the Islamic Conference Secretariat) and admonish the OIC that “during the last nine months (of 1971) when three million Bengalis were killed in cold blood by the West Pakistani forces you did not raise your voice to stop the killing of innocent Muslims and members of other communities in the second largest Muslim state.” This riposte was fired after the OIC Secretary General expressed his anxiety over the treatment of “Biharis and non-Bengali Muslims” in Bangladesh.

Later, on April 17, 1973, after the completion of investigations into the crimes committed by the Pakistan occupation forces and their auxiliaries, it was decided to try 195 persons for serious crimes, which included genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, breaches of Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions, murder, rape and arson. It was also decided that the trials of such persons and others associated in planning and executing such crimes would be held in accordance with universally recognised judicial norms. This argument and the related judicial process were to be central till his murder in August 1975. Unfortunately, his death also resulted in the setting aside of the entire judicial process. One can only hope that under the present government this trial will be activated and completed. We owe it to the millions who lost family members and the tens of thousands of women who were molested.

Many detractors of Bangabandhu have, after 1975, tried to portray him and Awami League as having given up Bangladesh’s interest in the context of relations with India. This is far from true. The Joint Communiqué issued at New Delhi on January 9 (before the return of Bangabandhu to Dhaka), following the visit of Bangladesh Foreign Minister Mr. M. Abdus Samad, thanked India for their contribution to the liberation struggle but also emphasised that “the Indian armed forces which had joined the Mukti Bahini in the task of liberation at the request of the Government of Bangladesh would be withdrawn from the territory of Bangladesh whenever the Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh would so desire.” This premise was strictly followed later on. Bangabandhu, after his return to Dhaka, openly thanked India for its past assistance and then requested that country to withdraw all its troops from Bangladesh. This was complied with immediately, and belied claims by the then Pakistani leadership that Bangladesh was going to remain as an Indian colony.

Another important achievement of Bangabandhu and his government was the creation of confidence among the war-affected citizens within the devastated country and also among the 10 million Bangladeshi refugees who had sought sanctuary on the other side of the border in India. By February 8, 1972, Mrs. Indira Gandhi, the Indian prime minister acknowledged in Calcutta that more than 7 million refugees had returned from India to Bangladesh in the short space of six weeks. The rest of them, that included hundreds of thousands who had been tortured by the Pakistani army, returned home within the following months, sure of a new beginning. Providing relief and rehabilitation to such a large population was a daunting task but handled efficiently by Bangabandhu and his team in cooperation with the United Nations.

Bangabandhu believed strongly in the sovereign equality of all nations. In this context (as Director of the India Desk in our Ministry of Foreign Affairs) I had the privilege of watching him stress on the promotion of close cooperation with India in the fields of development and trade “on the basis of equality and mutual benefit.” He also believed in cooperation and consistently stressed on the development and utilisation of resources “for the benefit of the people of the region.” It was this approach that led him eventually to persuade India to agree to the establishment of a Joint Rivers Commission on a permanent basis, comprising of experts of Bangladesh and India “to carry out a comprehensive survey of the rivers systems shared by the two countries and to formulate projects concerning both the countries in the fields of flood control and then to implement them.” In the Joint Declaration of the Prime Ministers of Bangladesh and India on March 19, 1972, at Dhaka, there was also a reference to examining the feasibility of linking the power grids of Bangladesh with the adjoining areas of India. The same Declaration also proposed that the two countries “shall have consultations and exchange information on peaceful uses of nuclear energy.”

Today, 37 years later, we are proposing a regional energy grid and regional water management for South Asia. Such a proposition is consistent with Bangabandhu’s vision of so many years ago.

Bangabandhu took keen interest in foreign policy and encouraged the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to undertake initiatives not only for obtaining recognition of Bangladesh by other countries and in the establishment of diplomatic relations but also in Bangladesh becoming a member of important international organisations. At every opportunity, during his own visits abroad, or that of the foreign minister, it was underlined that Bangladesh was determined to maintain fraternal and good neighbourly relations and adhere firmly to the basic tenets of non-alignment, peaceful co-existence, mutual cooperation, non-interference in internal affairs and respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty.

This vigorous effort enabled us to move forward in the arena of international relations very quickly. By March 26, 1972, when we were celebrating our first anniversary of independence, 54 countries had already recognised Bangladesh (as opposed to less than 10 before his return to Bangladesh). This number increased sharply by the end of 1972. I believe this was largely due to the positive measures undertaken by Bangabandhu and also because of the fact that he was able to persuade India to withdraw its troops from the territory of Bangladesh. Within a short time after that, Bangladesh became a member of the Non-Aligned Group, the Commonwealth, the ILO and the WHO and started playing an important role in the diplomatic arena. We obtained the status of Observer in the United Nations but were however unable to become a member because of the veto power of China (a close ally of Pakistan). This was particularly disappointing for Bangabandhu as he held China with respect and often recalled his own visit to that country in 1956. Our not being a member of the United Nations, however, did not deter Bangabandhu from seeking the humanitarian intervention of the then United Nations Secretary General Dr. Kurt Waldheim on November 27, 1972 in arranging the repatriation to Bangladesh of innocent Bangalees detained in Pakistan in different camps. He did so because Pakistan was trying to politicise the issue and link their repatriation to the release of Pakistani POWs who had surrendered to the joint command of Bangladesh and Indian forces. This concern on his part was an example of his love for his countrymen.

He believed in nationalism, democracy, secularism and socialism. He felt that they were required for the good of the common man and for the success of the social revolution. He also thought that his idealistic “new world” would be free from exploitation and injustice, have equality in the distribution of wealth and the presence of small and cottage industries would be a means of solving the unemployment problem. He also tried to reform the land ownership system by instituting family ceilings.

Bangabandhu was a firm believer in the rich cultural and literary heritage of Bangladesh, and for him that was the spring-board of the Bangalee ethos, its tradition and its nationalism. That instilled in him the pride of being a Bangalee living in Shonar Bangla.

His was a life of sacrifice. It is such a pity that his efforts were snuffed out at such a relatively young age. His passing away introduced several detracting factors in our system of governance — the principal being the lack of accountability. We owe it to his memory to try and do our best in achieving the dream of a developed Bangladesh where there is equal opportunity for all citizens and the practice of rule of law.

Author : Muhammad Zamir, Muhammad Zamir is a former Secretary and Ambassador.